Ailments affect all kinds of people. But images doctors see in their textbooks and research journals don’t often reflect that. AI just makes it worse.

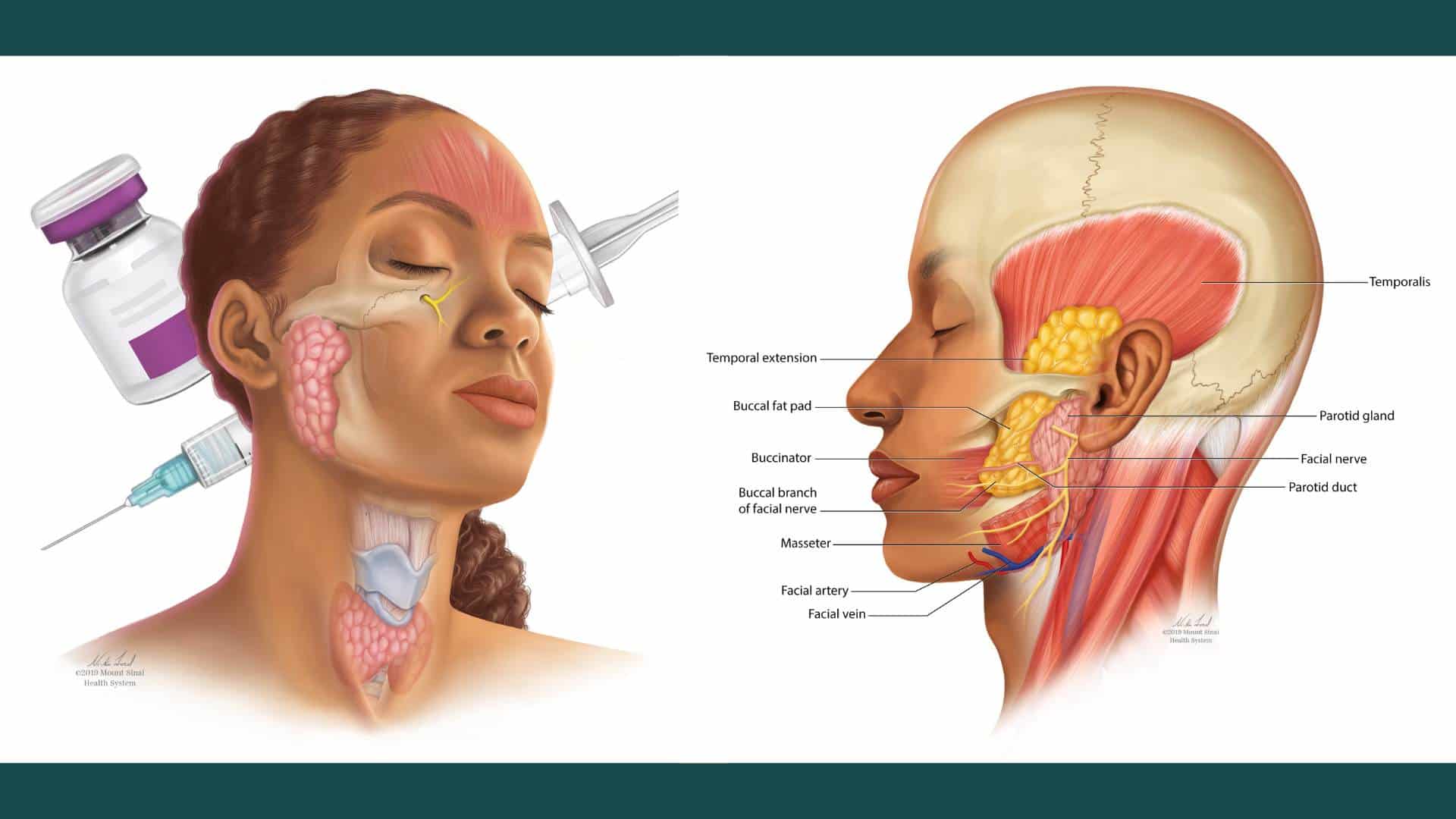

Two medical illustrations by artist Ni-ka Ford. On the left is a depiction of botox injections. On the right is an illustration for a journal article on the buccal fat pad and the anatomical structures surrounding it. (Courtesy of Ni-ka Ford)

Medical illustrations help train health care professionals to recognize illnesses and conditions. Meanwhile, only 4.5% of medical textbook images show dark skin, according to one recent study.

A 2021 analysis found that 18% of the medical images in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine depicted non-white skin.

“All of the medical images in our textbooks when I was in school were of people of European descent,” said Dr. See-Wei Low, a pulmonologist at the Cleveland Clinic in the U.S. state of Ohio, who is native of Malaysia.

The lack of diversity in medical illustrations has profound effects.

Depicting darker skin in medical books is significant because it allows clinicians to recognize conditions or diseases in patients with different skin color. The experiences and needs of people of color (POC) are often overlooked or misunderstood, contributing to incorrect diagnosis.

Coloring the way we view illustrations

Medical illustrators are professional artists with advanced education in life sciences and visual communication. They are visual problem solvers who promote education, research, patient care, public relations and marketing efforts.

Illustrators are asked to create art ranging from cellular graphics, physiological or procedure processes to journal and textbook covers. It is a competitive profession to get into. Only 10 universities in the world offer this degree and they each accept 7–20 students per year. The field is constantly changing due to discoveries in science and technology.

There are roughly 2,000 professional practicing medical illustrators in the world. This small group is responsible for creating medical illustrations that represent a global population of more than eight billion people. Only about 8% of these illustrators identify as POC. Meanwhile 43% of the U.S. population is non-white.

Representation in medical illustrations also gives POC a sense of relatability, according to academics, clinicians, scientists and illustrators of color, especially if they’re not used to seeing those in STEM careers who look like them.

“I’ve always been an artist,” says medical illustrator Ni-ka Ford. “So initially, when I walk in a room, I’m always looking at something that’s artistic.”

Diversifying the people who can diversify drawings

Ford founded Enlight Visuals, a medical illustration and design studio specializing in accurate and inclusive medical visualization for healthcare materials and medical and scientific literature.

“I noticed even at the dentist, the medical illustrations at the office were all of usually white men, so I just never felt like any of it related to me,” Ford said. “I didn’t feel I gravitated towards any of the imagery, and it didn’t speak to me at all.”

The lack of representation can also have psychological effects on people of color in considering a STEM career. People tend to internalize what they see as possibilities for themselves, said Angela Byars-Winston, psychologist and professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“When we think about the importance of representation whether it’s in person, mentoring, as a researcher, as an educator or what we see visually in our books, we know that these images suggest to us relatability and possibility relatability,” Byars-Winston said. “In that sense, can I see myself doing that? Do I relate to that person? Do people like me do this kind of work? And the possibilities then become options for me thinking about aspirations.”

In the few cases where people of color are actually represented in scientific art, it’s usually associated with a disease or condition depicting a negative stereotype such as malnourishment or sexually-transmitted infection.

“For people who do this kind of work, it’s our duty to reverse the harm that has been caused by this lack of representation,” said Ford.

Representation not assimilation

The appetite for diverse medical illustrations is shown by the rising celebrity of medical student Chidiebere Ibe of Copperbelt University in Kitwe, Zambia, who began creating illustrations in 2020 as a way to combine his artistic talent with his dream of becoming a doctor. Ibe’s life would soon change when his 2021 illustration of a pregnant Black woman and her fetus went viral.

The success of his illustration(s) have not only helped him fund his schooling, but made him a leading advocate for representation in scientific art with his role as chief illustrator of the Journal of Global Neurosurgery, teacher of a new class of medical illustrators out of Africa and author of the book “Beyond Skin: Why Representation Matters in Medicine.”

That’s the sort of thinking that’s changing the traditionalist mentality in medical illustration.

People of all races, ethnicities and cultures have participated in science and medicine for a long time, but it is only recently that scientific art has begun to change and expand, says Dr. Crystal Starbird, structural biologist and professor at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

“Before, people were taught that they had to work on assimilating,” she said. Now they are able to render what they actually see, and not what is expected of them.

Diversity starts at the top.

The major contributor to the lack of diversity in scientific art is the lack of representation of people of color on the boards, committees and organizations that decide what is published.

Starbird describes the struggles she and other illustrators and scientists have had trying to publish their scientific art.

“It’s a pick your battles thing,” Starbird said. “It’s like, ‘Oh, I’m not going to pick my battle over a figure that might look wrong to the editor.’”

Earlier in her career, as is the case for many junior scientists and illustrators, she would surrender too easily. “And so I’m going to give in when it comes to the figure because in terms of negotiating, that’s not the thing where I want to sort of make a stand,” she said.

These days, Starbird takes a tougher stand. She has had some of her manuscripts rejected in scientific journals because she refused to change illustrations she thought needed to be represented in a certain way.

AI can reinforce inaccurate stereotypes.

The era of AI has revealed systemic bias and has offered new challenges. AI generated images have been shown to inaccurately depict people of color. These multiple studies in 2023 published in The Lancet Global Health led editors of the Lancet journals to announce that they would develop new image guidelines.

In January 2023, The Lancet Global Health published a study showing how photos of people of color and low-income and middle-income countries from key global health organizations reinforced biases and perpetuated harm rather than challenge the issues needed to be addressed, to achieve global equity in health and wellbeing, due to the use of inappropriate imagery.

Later, Arsenii Alenichev, Patricia Kingori and Koen Peeters Grietens published a study about their attempt to reverse the stereotypical global health tropes that can be perpetuated through the images chosen to illustrate publications on global health.

They believe that AI, which uses real images as a basis for learning, might further serve to show how deeply embedded the existing tropes and prejudices are within global health images, which can perpetuate oversimplified social categorizations and power imbalances.

Using the Midjourney Bot Version 5.1, their results showed that AI was incapable of avoiding the perpetuation of existing inequality and prejudice.

When asked to render multiple scenarios doctors and patients in Africa, many of the images generated were of general stereotypes such as the suffering subject and white savior, where the recipients of care were always rendered Black.

AI also generated images of doctors and patients with exaggerated and culturally offensive African elements such as wildlife.

“You didn’t get any sense of modernity in Africa,” said Kingori in an interview with National Public Radio in the United States. “It’s all harking back to a time that, well, it never existed, but it’s a time that exists in the imagination of people that have very negative ideas about Africa,” she said.

Results also showed that AI couples HIV status with Blackness. Out of the 152 prompted HIV patient images, 150 were rendered Black.

Making medical drawings more representative

With awareness of the lack of representation in scientific art now heightened, a larger push has been made to address the issue.

Illustrators have become more focused on creating more diverse illustrations.

In June of 2023, pharmaceutical giant Johnson & Johnson launched the Illustrate Change initiative that aims to increase diversity and representation in medical illustrations. Johnson & Johnson also funded the AMI Diversity Fellowship with the Association of Medical Illustrators, which gives 10 fellows the task of creating 10 illustrations each of diverse individuals which will then be added to the Illustrate Change website.

The Animation Lab of the University of Utah created the Seeing Diversity project led by Dr. Janet Iwasa, where each month an Animation Lab member works with a molecular, cell biologist or biochemist of color to create a visualization that captures their scientific contributions.

On an individual level, Starbird plans to use her influence as a Principal Investigator to embrace people in her lab, expressing themselves visually the way they want. “And when people complain, I’m going to defend them as strongly as I can,” said Starbird.

There are also many medical schools and their associated teaching hospitals that are making greater efforts to include more DEI into their education programs, which includes scientific art.

“The goal is to help us understand that the representation benefits all of our minds being expanded,” said Byars-Winston.

Questions to consider:

-

- How can homogenity in medical illustrations cause harm?

- What are some publishers and research universities doing to bring diversity to medical illustrations?

- Do you think it is important that people who draw medical illustrations be themselves representative of a diverse population? Why?

Lance Roller II is a U.S.-based researcher, data analyst and freelance journalist. He is currently a fellow in the Dalla Lana Fellowship in Journalism and Health Impact at the University of Toronto.

Read more News Decoder stories about racism and discrimination: