In 1962 reporters arriving in Vietnam found an increasing U.S. military presence that wasn’t supposed to exist. Reporting what was happening took courage.

Associated Press correspondent Peter Arnett, left, marches in column with Vietnamese troops as he covers the war in Vietnam, 11 November 1965. (AP Photo)

This article was produced exclusively for News Decoder’s global news service. It is through articles like this that News Decoder strives to provide context to complex global events and issues and teach global awareness through the lens of journalism. Learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program.

At age 27, Peter Arnett arrived in Vietnam to “beef up” the Saigon bureau of the Associated Press (AP), a global newswire service. It was 1962, and the Pentagon was clandestinely increasing the numbers of U.S. military advisors sent to support the government and army of South Vietnam against its communist-led adversary in the north.

Arnett and the other reporters there tried to tell the global public what was happening in the former French colony, but they met with obstacles put in place by the U.S. military to prevent reliable coverage from getting out. Secrecy was needed because the U.S. buildup was taking place in defiance of limits set by the 1954 Geneva Accords.

Now 89, Arnett spoke about his experience, along with other news veterans who covered the war. Among them were Edith Lederer, 81, who joined that AP bureau as its first woman reporter in 1972 and still works full-time as the AP’s chief correspondent at the United Nations, and Fox Butterfield, 85, who was dispatched to Saigon by the New York Times in 1971. Their panel discussion, held this spring at Columbia Journalism School, was part of a history department conference titled “Legacies of the Vietnam War.”

Arnett noted that more than 60 reporters and 58,000 U.S. soldiers lost their lives in the conflict.

“This is an opportunity for all of us to hear about the kind of suffering that went on amongst the civilian population,” Arnett said. “About a million people, civilians, died in the Vietnam War. This was a real war. The American public deserved to know what the hell was going on.”

A different way of reporting war

Arnett said that as U.S. presence in Vietnam swelled from 8,000 to 12,000 military advisors by the end of 1962 and to 25,000 by mid-1963, he and his fellow reporters struggled to pierce the denial that was becoming the official American response to evidence of the buildup.

Born and brought up in New Zealand of partial Māori heritage, Arnett launched his journalistic career in southeast Asia. Stationed in Laos in 1960, he swam across the Mekong River to Thailand daily — passport, cash and story in his teeth — to file uncensored news of a coup in Vientiane.

In 1964, Arnett married his Vietnamese wife, Nina Nguyen, fathered two children and worked in Vietnam until after Saigon fell to North Vietnamese forces more than a decade later.

He recalled how reporters once summoned a U.S. embassy official to the Saigon River dock where an aircraft carrier was delivering scores of helicopters. Asked for comment, the official stated: “I don’t see anything!”

Arnett described “brutality in the streets,” as he and fellow members of the press corps were badly beaten and arrested by local police simply for doing their jobs: covering protests against the U.S.-backed South Vietnamese regime.

“The American government didn’t give a damn about us,” Arnett said. “They didn’t move to stop the Vietnamese. Why? Because by knocking us back, [police] were taking care of their problem. The press was getting in the way of the U.S. getting involved in Vietnam and ‘winning the war.'”

From one war to another

Arnett would become a household name in the United States in the 1990s as part of a CNN team broadcasting live coverage of the U.S. bombing of Baghdad, which marked the launch of the first Gulf War in 1991. In that conflict, many reporters covered the war “embedded” with the U.S. military, under procedures that differed markedly from how the press had covered the Vietnam War.

And the young reporters covered Vietnam with a far less cooperative spirit than the press had shown in the two world wars and the Korean War, Arnett said.

“The problem was that the U.S. military expected the press to be obedient,” he said. In Vietnam, with fierce competition among reporters and without control over what was being published, reporters challenged the military authority. “Commanders didn’t understand why stories appeared that they found offensive,” Arnett said.

Unlike Arnett, Lederer first came to Vietnam as a “war tourist,” not a correspondent. On vacation from her job with the Associated Press in San Francisco and enjoying an around-the-world air ticket deal, Lederer popped in to visit the Saigon bureau in 1971.

She impressed staffers there, who took her to a U.S. military press conference (also called the “five o’clock follies”) and on a helicopter ride. When a vacancy arose in Saigon a year later, Lederer’s name came up, and she had listed “foreign correspondent” as her career goal on a personnel form.

By that time, four AP photographers had been killed in Vietnam and the wire service was leery of sending women overseas, even more so to war. Management overcame their qualms, and Lederer took up her new post in October 1972.

To capture the human side of the conflict, Lederer developed feature stories on the horrendous toll the war was taking on ordinary Vietnamese. Traveling to a nearby village, she talked with a woman whose husband and three adult sons had been killed in battle, leaving her to support five young children in a one-room shanty.

Reporting the human side of war

When news came that “peace was at hand,” and U.S. troops were given a 60-day window to ship out, Lederer wrote a human interest story about “bar girls.” For three nights, she made the rounds of Saigon night spots, interviewing women whose boyfriends and even the fathers of some of their children would soon be leaving.

Lederer co-authored the 2002 book “War Torn: Stories of War from the Women Reporters Who Covered Vietnam.” In it, she described a recurring dream: being jolted awake by explosions in Vietnam. Calling her nightmare a “microcosm of my life there,” she writes that it reminds her of “those mad, crazy, sometimes dangerous days that I lived with an intensity only occasionally matched in the wars I went on to cover.”

Few Vietnam War correspondents are still practicing their profession, but ever since Lederer left Saigon in 1973 to cover war in Israel, she has been reporting on conflicts and famines everywhere. To this day, at 81, she helms the AP bureau at UN headquarters in New York.

She agreed with Arnett’s views on war reporting and government censorship, saying that it has hampered coverage of every U.S. war since Vietnam.

She contrasted the adverse relationship between the military and press in Vietnam with how media coverage of the 1983 U.S. invasion of Grenada was handled during President Ronald Reagan’s administration.

“In Grenada, the Pentagon took a press pool that never got out of the airport,” Lederer said. “In the first Gulf War, when I was running the AP in Saudi Arabia, the controls were incredible. Those controls remain today. That’s how journalists get into the field now, with a military escort. The ability to go out and see for yourself on your own terms does not exist anymore.”

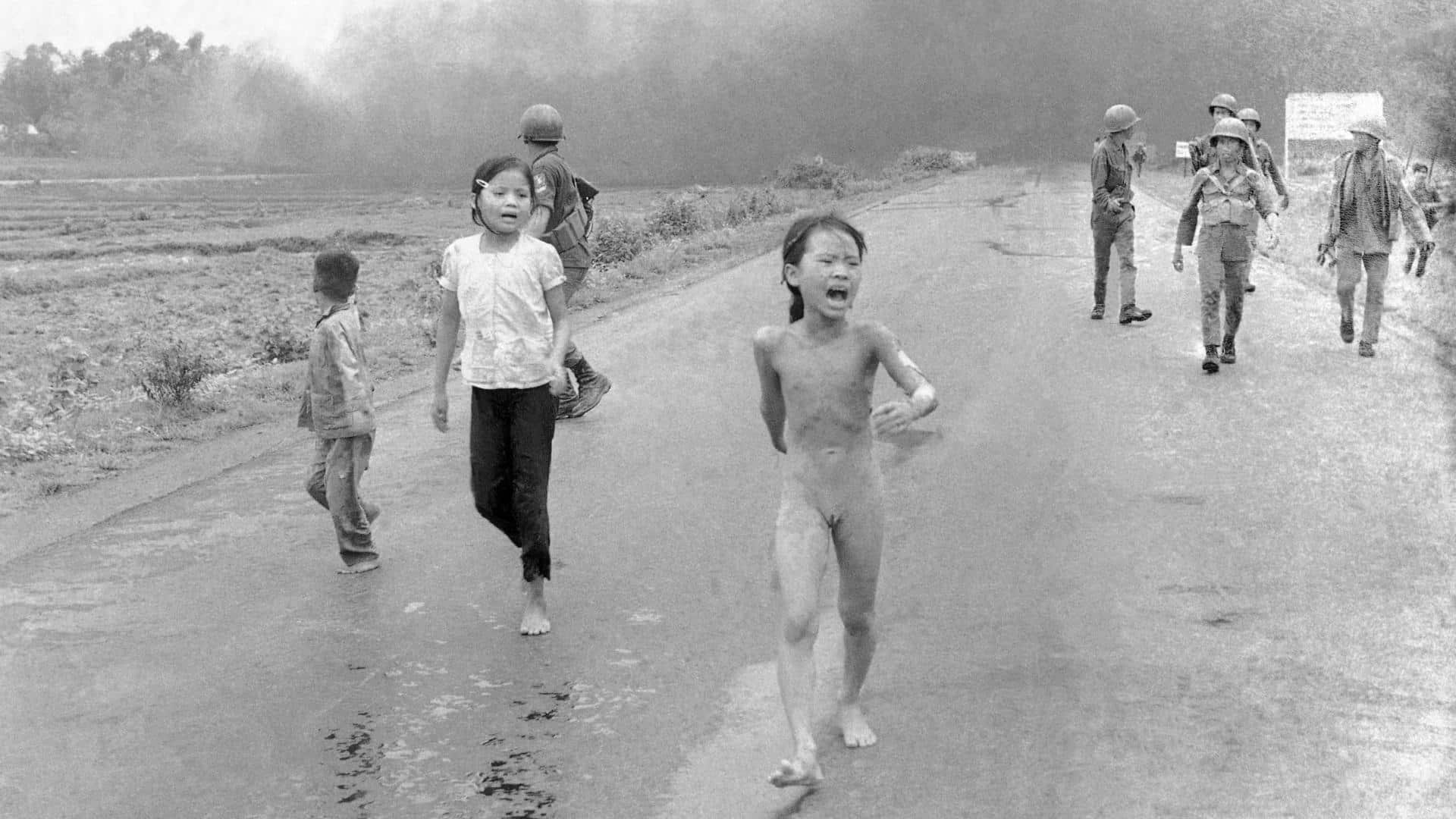

South Vietnamese forces follow after terrified children, including 9-year-old Phan Thị Kim Phúc, center, as they run down Route 1 near Trang Bang, Vietnam on 8 June 1972 after an aerial napalm attack on suspected Viet Cong hiding places. A South Vietnamese plane accidentally dropped its flaming napalm on South Vietnamese troops and civilians. Kim Phúc had ripped off her burning clothes while fleeing. (AP Photo/Nick Ut)

The “living room war”

Butterfield was no stranger to Vietnam when the paper sent him to Saigon in 1971. Like Lederer, he’d first visited as a tourist in 1962.

Fluent in Mandarin, with two degrees in East Asian studies from Harvard, Butterfield started stringing for the New York Times in Taiwan while on a Fulbright scholarship there. Shortly after North Vietnamese President Ho Chi Minh died in 1969, Butterfield pulled off an astonishing coup.

Wrangling a visa and permission to interview the new leaders in Hanoi in the north of Vietnam, Butterfield even conducted one of those conversations in Chinese. Freelance articles he wrote about the trip for the Times magazine helped seal his fate. He gave up doctoral studies and joined the newspaper’s staff.

“They sent me to Vietnam because I was single and expendable, as a ‘reward’ for working on the Pentagon Papers,” Butterfield said at Columbia. “Vietnam was sometimes called the ‘living room war’ because so many Americans watched it play out on their television sets,” he said. “One TV guy I knew there told me he kept calm under fire by pretending he was looking through a camera viewfinder — like watching TV.”

In Long Trach village, two hours south of Saigon in the Mekong Delta, Butterfield said he discovered the “real Vietnam.” Some of his best stories emerged in conversations with the villagers there, he said.

Their “loyalties shifted back and forth like the tides” at any given time, depending on whether the Viet Cong or the south Vietnamese army were in control, he said.

Butterfield, now retired after more than three decades with the Times, credited his predecessor in Saigon, Gloria Emerson, for showing him the ropes during his first three months and for introducing him to Long Trach. Emerson, who died in 2004, was the first woman sent to Vietnam as a Times correspondent.

“I inherited Gloria’s flat and even her dog Snookie — named for Cambodia’s Prince Sihanouk. She carried Snookie back from Phnom Penh in her handbag,” he said.

At the conference, he displayed a treasured keepsake: a small notebook Emerson had given him back in the day.

Covering a defeat

Butterfield would spend four years covering war in Vietnam, staying until the fall of Saigon, when he was evacuated by helicopter. Given three days to go home and visit family, he was then posted to Hong Kong.

In 1979, when China normalized relations with the United States, Butterfield opened the first Beijing bureau for the Times. His book “China: Alive in the Bitter Sea” won a National Book Award in 1983.

Butterfield said he is haunted by the memory of a 9-year-old girl running naked down the street, her skin burning from napalm and his colleague, David Burnett, frantically trying to put another roll of film in his camera. Associated Press photographer Nick Ut captured the shot in a 1972 news photo that shocked the world and won the Pulitzer Prize.

The girl in the photo, Phan Thị Kim Phúc, would forever be known as “Napalm Girl.” Now 61, Kim Phúc was the keynote speaker at the conference. A peace activist and UNESCO Goodwill ambassador, Kim Phúc spoke of enduring 17 surgeries and years of pain while finding a way to overcome her feelings of hatred and rage.

She described how she spent years ridding her heart of anger and bitterness. Each day she imagined pouring out a splash of hatred, as if emptying a cup of black coffee. Then, day by day, she filled the cup with drops of clean, clear water.

Butterfield praised her “special dignity.”

“She’s a wonderful person,” he said.

Three questions to consider:

- In what ways did journalists cover the Vietnam War differently from war correspondents of the past?

- What made covering the Vietnam War difficult for the reporters there?

- What are the positives and negatives of “embedding” with the military to cover a war?

Susan Ruel worked on the international desks of the Associated Press and United Press International and reported for UPI from Shanghai, San Francisco and Washington. She has written and edited articles and books for the United Nations, including reports from Nigeria. A former journalism professor with a PhD in writing and literature, she co-authored two French books on U.S. media history and was a Fulbright scholar in West Africa. Based in New York City, she currently serves as an oncology editor for a medical news website.