Some worry that the prosecution of Julian Assange could set a precedent for prosecuting anyone who disseminates information gathered by whistleblowers.

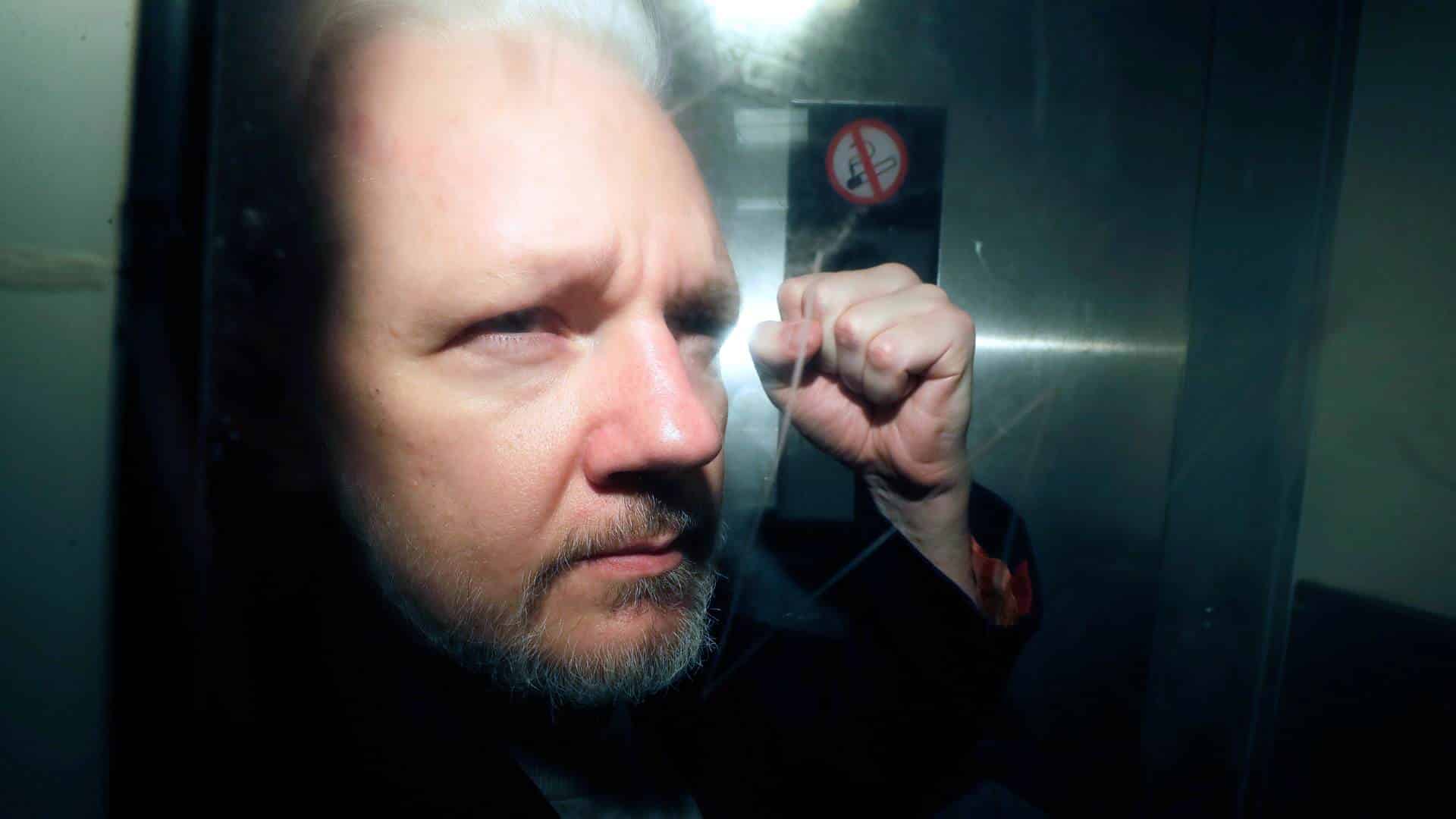

WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange shown being taken from court, where he appeared on charges of jumping British bail seven years ago, in London, 1 May 2019. (AP Photo/Matt Dunham)

Editor’s Note: 3 May marks World Press Freedom Day, first established by the United Nations in 1993 as a reminder to governments and citizens of the important work done by journalists around the world and the need to protect those journalists from harassment or harm.

To mark the day, News Decoder is publishing three stories. We started 1 May by republishing an article we first ran in May 2023 by Rafiullah Nikzad, about the mass exodus of journalists from Afghanistan and the aftermath of severe censorship for those who remain.

Today we publish publish a story by student author Joshua Glazer that examines the question of who is a journalist and therefore worthy of press protections. On 3 May, we will publish an article by correspondent Helen Womack that looks at the continued imprisonment of Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich in Russia and Vladimir Putin’s use of arrest and imprisonment as a tool of power and oppression.

In 2020, a group of bystanders in the U.S. state of Minnesota recorded on video the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police and then posted these videos onto social media.

Should we consider bystanders who witness events and publish photos, journalists? The question is pertinent to the continued prosecution of hacker and publisher Julian Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks.

Is anyone who obtains documents and publishes them a journalist? How we answer that question will affect whether or not one believes that the persecution of Assange is an attack on the press and a violation of the Western notion of freedom of the press.

Journalist Charles Glass, who considers himself a friend of Assange, says yes.

The prosecution of Assange and Wikileaks is a complex legal battle that raises critical questions about the delicate balance between freedom of speech and press, the role of technology in the media and the responsibility of journalists.

Fighting extradition

Assange became a target of the U.S. government after he published millions of classified and leaked documents from governments around the world. He was confined for seven years to the Ecuadorian embassy in London where he sought asylum from charges levied in Sweden on accusations of rape. These were later dropped. Since 2019, Assange has been in a London prison fighting extradition to the United States.

Glass has covered civil wars, hostage negotiations and corrupt governments and has written numerous articles on Assange’s prosecution. He is one of a group of journalists who filed suit in 2022 against the CIA for spying on them while they visited and interviewed Assange.

Glass argued that anyone who disseminates information to the public is a journalist. The essence of journalism, he said, lies in conveying information or opinion, irrespective of the medium used.

Molly Rose Ávila, who teaches Advanced Journalism at Avenues: The World School in New York City, where I attend school, said that just because Assange is an activist doesn’t mean he isn’t a journalist. Advocacy and activism are inherent in journalism, she said. But journalists should not cross ethical boundaries, especially when the dissemination of information could cause direct harm to individuals.

Assange’s case raises significant questions about the implications of the Espionage Act of 1917, which aimed to prosecute individuals who tried to collect and reveal national defense-related information with the intention of harming the United States.

Whistleblowers v. spies

Complicating Assange’s case is that he was not a whistleblower who collected information, but the publisher of that material. The Espionage Act does not provide safeguards for journalists who publish material collected by whistleblowers. Instead it treats journalists as accomplices.

Had Assange crossed a line by revealing military secrets and exposing assets? Glass argues no. “Assange, even by the admission of the Pentagon and the State Department did not put anyone’s life in jeopardy,” Glass said.

He pointed out that Assange redacted information in cooperation with reputable news organizations that include the New York Times, Guardian and El País.

For Ávila, at the heart of this debate is whether or not it is possible to produce unbiased journalism.

She argues that it is because humans are biased that gives them an advantage over AI. “Journalists are people, they are affected by things,” Avila said. “Journalists have preferences, journalists have political views, journalists experience love and anger and have been discriminated against.”

The role of the journalist

Because journalism is fundamentally a human interpretation of information, and therefore biased, people or organizations that will publish something without interpretation — such as many of the people who video something happening and post to social media, or an organization like WikiLeaks that posts documents others collect — are not journalists and don’t necessarily deserve the special protections that many people think journalists should have.

I think that the prosecution of whistleblowers, individuals who have hacked government software, should be prosecuted under the Espionage Act or other acts. But while Assange might have crossed the line in terms of his protection against the law, prosecuting him under the Espionage Act is not the solution.

The answer is that there is no clear solution. I believe that we must ensure the protection of investigative journalists who may reveal information that could harm the image of a nation in the eyes of the public. We need to do so by focusing on intent and harm — in other words, the leaked information being published is done so for the benefit of the public, and not for malicious purposes or to endanger lives.

Defining this boundary, this gray line, must be drawn up by both politicians and investigative journalists to make certain that journalists are not discouraged from publishing information nor from being charged with a crime if they do so.

Assange’s case is an example of the tension between press freedom and state power. Glass challenged narratives surrounding Assange’s alleged harm, and framed Assange’s persecution as emblematic of a broader assault on journalistic freedom.

Playing a dangerous game

There are several similar cases to Assange, such as Edward Snowden’s leaking of documents from the National Security Association in 2013, and the imprisonment of Texas writer Vanessa Legget in 2001 for refusing to hand over notes that could be used to help the police with a criminal investigation.

In response to Legget’s imprisonment, the International Federation of Journalists said at the time, “The authorities play a dangerous game when they start to pick and choose which writers and journalists are entitled to the protection of the Constitution.”

The Assange saga, along with many other examples of whistleblowing in today’s digital age, illuminates the intricate relationship between journalism, technology and government accountability.

As society grapples with the implications of WikiLeaks’ revelations, fundamental questions about press freedom and ethical responsibility arise.

As we navigate these challenges, we need to champion transparency, ethical standards and democratic principles, to ensure that journalism remains a vital force for accountability and social change in the digital age.

Avenues students Matthew Lee, Sebastián González Vázquez and Charles Cushman assisted in this story.

Three questions to consider:

- In what ways can Julian Assange be considered a journalist?

- Do you agree with the author that the prosecution of individuals who hack government software should be prosecuted under the Espionage Act?

- Should journalists be given special protection against prosecution for publishing material given to them by whistleblowers?

Joshua Glazer is in his second to last year of high school at Avenues: The World School in New York, and studied abroad at School Year Abroad Spain in the fall semester. He is a News Decoder Student Ambassador.

Read other News Decoder stories about press censorship: