In Finland, teaching media literacy in schools is a way to stave off the disinformation invasion that looms on its border.

The design on the cover of “The ABC Book of Media Literacy.” (News Media Finland)

From 24 to 31 October, the world marks Global Media and Information Literacy Week, an annual event first launched by UNESCO in 2011 as a way for organizations around the world to share ideas and explore innovative ways to promote Media and Information Literacy for all.

For this year’s theme — “The New Digital Frontiers of Information: Media and Information Literacy for Public Interest Information” — News Decoder presents a series of articles and a Decoder Dialogue webinar on different aspects of media literacy.

We launch this series today with a look at an effort in Finland to make media literacy a core component of primary education. For our Friday Top Tip, we explore the concept of media framing and ways news can shape thought. On Monday, 28 October, we present a compilation of articles and other resources on media literacy. And on Tuesday 29 October we look at the role of artificial intelligence in disinformation with an article and live Decoder Dialogue: From Newsrooms to Classrooms: Real Talk About Artificial Intelligence at 18:00 CET. It promises to be a lively online roundtable that will bring together experts and students from six countries to talk about fears and hopes for the new technology.

We end the series 30 October with a Decoder Replay of an article that looks at the ramifications of using labels to identify groups of people.

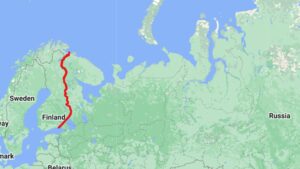

There might be no nation that recognizes the need for media literacy more than Finland, which shares a 1,343-km (830-mi) border with Russia.

The contrast between the two countries is stark.

Russia has “banned, blocked and/or declared ‘foreign agents’ or ‘undesirable organizations’” nearly all independent media, according to Reporters Without Borders. And it has been caught waging online disinformation campaigns to disrupt elections in other countries, including the United States, Moldova and Georgia.

In Finland, in contrast, media literacy is considered the second-most important literacy skill after basic reading. As a result, Finland has one of the highest media literacy rates in the world.

To boost media literacy, News Media Finland, an association of 93 news organizations, has published a primer on media literacy that was published in August and distributed to every ninth grader in the nation – some 65,000 copies. The organization also offers a digital version of the primer in Finnish, English and Swedish.

Teaching media literacy as easy as ABC

For Jukka Holmberg, the president of News Media Finland, the hope is that the next generation will be able to recognize Russian and politically-charged misinformation. The eventual goal of such information would be to limit freedoms, like freedom of the press.

The primer — an informational book dubbed the “ABC Book of Media Literacy” — connects each letter of the alphabet to pillars of media literacy.

D is for “Democracy,” in which it cites the foundations of democratic societies as needing “extensive, reliable and high-quality journalism.” F is for “Fact,” delving into the area of fact-checking: “Credibility and truthfulness are at the heart of journalism.” N, for “Narrative,” ventures into how “language can be used in a more free and personal way than in a formal style of writing.” But this also comes with a nuanced “responsibility and a strong commitment to truthfulness and ethical journalistic guidelines.”

It might follow the alphabet, but the ideas in it are fleshed out and complex. It is, after all, meant to be taught — not just read — in the classroom.

Everyone should understand the role of journalism in democratic countries, like freedom of speech, said News Media Finland’s Project Manager Susanna Ahonen.

“We have to educate every generation, again and again and again,” Ahonen said. “So even though we are the best in the world, it doesn’t stay that way if we are not constantly working on this. It’s a project forever.”

Teach kids to think before they share.

News Decoder User Experience Manager Sabīne Bērziņa said that by definition media literacy is the ability to consume, analyze and create media in a responsible and critical manner.

“You’re not only able to evaluate if the information is truthful and the source is worth trusting, but also when you create or share anything, you keep in mind that all of these actions also influence the information space we live in,” Bērziņa said.

Engaging with content in any shape or form impacts how it gets presented to other people, she said. “And therefore you also take responsibility of your own role and don’t do things impulsively just because they’re attention grabbing or fun, but do it in a thoughtful, critical way,” Bērziņa said.

Media literacy will be a focus of News Decoder’s next Decoder Dialogue webinar 29 October on artificial intelligence in the classroom and journalism hosted by Bērziņa. In it, data scientist and AI futurist Nikita Roy, Swedish educator Johan Sköld and digital media consultant Sonali Verma will discuss with several students from different countries the benefits and dangers of artificial intelligence.

Bērziņa, who leads the Promoting Media Literacy and Youth Citizen Journalism through Mobile Stories (or ProMS) project, worked as a journalist for seven years before she started working with media literacy. At the height of the Covid-19 pandemic she was a fact checker and disinformation reporter.

“It was a period where our lack of media literacy and our lack of critical thinking really stared all of us in the face,” Bērziņa said.

Where disinformation lies

It also brought out a hard truth: misinformation is found in “unpleasant, conspiracy-filled information spaces,” Bērziņa said. It is also commonly found in all our social media timelines.

“A big part of teaching about media literacy is teaching people to pause,” Bērzina said. “We all like fun things, but if you’re also aware that you have the responsibility to only pass around verified information, you might think about it at least a little bit before you pass it on. We don’t have a lot of control of what flows in our timelines.”

Where media literacy rates are high, people tend to trust journalistic sources more. For comparison, while only 34% of Americans have trust in the media, 76% of Finnish citizens do.

For the fifth year in a row, Finland clocked in first out of 41 European countries on resilience against misinformation in a survey published in October by the Open Society Institute in Sofia, Bulgaria.

Staying vigilant against falsehoods

While Holmberg recognizes Finland’s media literacy success, he said it is important to see it as a step in the right direction, and an ongoing process.

A map shows the border of Finland and Russia.

This healthy skepticism and an appreciation for ethical journalism in Finland is a layer of international security protection in a place where disinformation has geopolitical dimensions.

“It’s very difficult to come to Finland with biased social media, or in any way to push the Russian view to Finnish minds,” Holmberg said.

Ahonen said Finland can still fall prey to Russian disinformation. “They are quite clever and they are quite sneaky,” she said. “But the core remains that we are more resilient to Russia than many others.”

Vigilance and skepticism is important. Bērziņa said that the problem is that much misinformation is easy to believe if you distrust the government, the media and don’t take much time to evaluate evidence.

“How a lot of conspiracy theories get born online is people thinking, ‘Is it possible for this to happen?’ And if it is, and if they can come up with it, they take it as evidence for it,” Bērziņa said. For example, if a journalist makes a mistake and you distrust journalists, you might believe they had received money to write something that’s wrong, she said. In reality, maybe they just did not know any better. To prove that it’s the result of corruption, you would need evidence.

“If the person goes through some education related to critical thinking, they simply don’t subscribe to that sort of thinking — this fast thinking, this impulsive thinking — but they start requiring evidence,” Bērziņa said.

Mustering forces in the information war

News Decoder itself hosts campaigns and webinars to tie in the role of journalism in media literacy. But, as Bērziņa puts it, no single element alone solves the problem. It’s working “towards systematic solutions that go towards all of society, not just the few.”

As for Finland, the media literacy warriors staring down an entire country which champions little to no press freedoms hope that other countries will be inspired.

“I see that the free media has a role in that when it reports on potential problems or abuses in society,” Holmberg said.

When people trust the press, they trust that the press will inform them of problems in society, big and small, he said. “So people can think that if nothing is heard, all is well,” he said.

That’s also how free media increases trust in other institutions, the press has to be independent and free to play that role, Holmberg said.

And so a little book teaching media literacy in the classroom becomes something much bigger: a way to teach children the importance of reliable information and the role of the press.

“For us, and, well, everywhere in the free world, the press is the institute to protect democracy,” Holmberg said. “That is the only reason why we exist. If there is no press, there is no democracy. And if there is no democracy, there is no press.”

Three questions to consider:

- Why is media literacy so important in Finland?

- How does the United States compare to Finland in media literacy rates?

- In what ways does media literacy connect to the strength of a democracy?

Kaja Andrić joined the News Decoder team as an intern in January 2024. She is a second-year Journalism student at New York University. She is also studying Romance Languages with a concentration in French and Italian. Andrić has written for both NYU’s Washington Square News and Cooper Squared publications. Previously, she was a correspondent for the Florida Weekly newspaper’s Palm Beach community chapter. In 2022, she was Florida Scholastic Press Association’s Writer of the Year.