Millions die of hunger in one place. No one cares. Millions are dying of hunger somewhere else and the world sends food. What’s the difference?

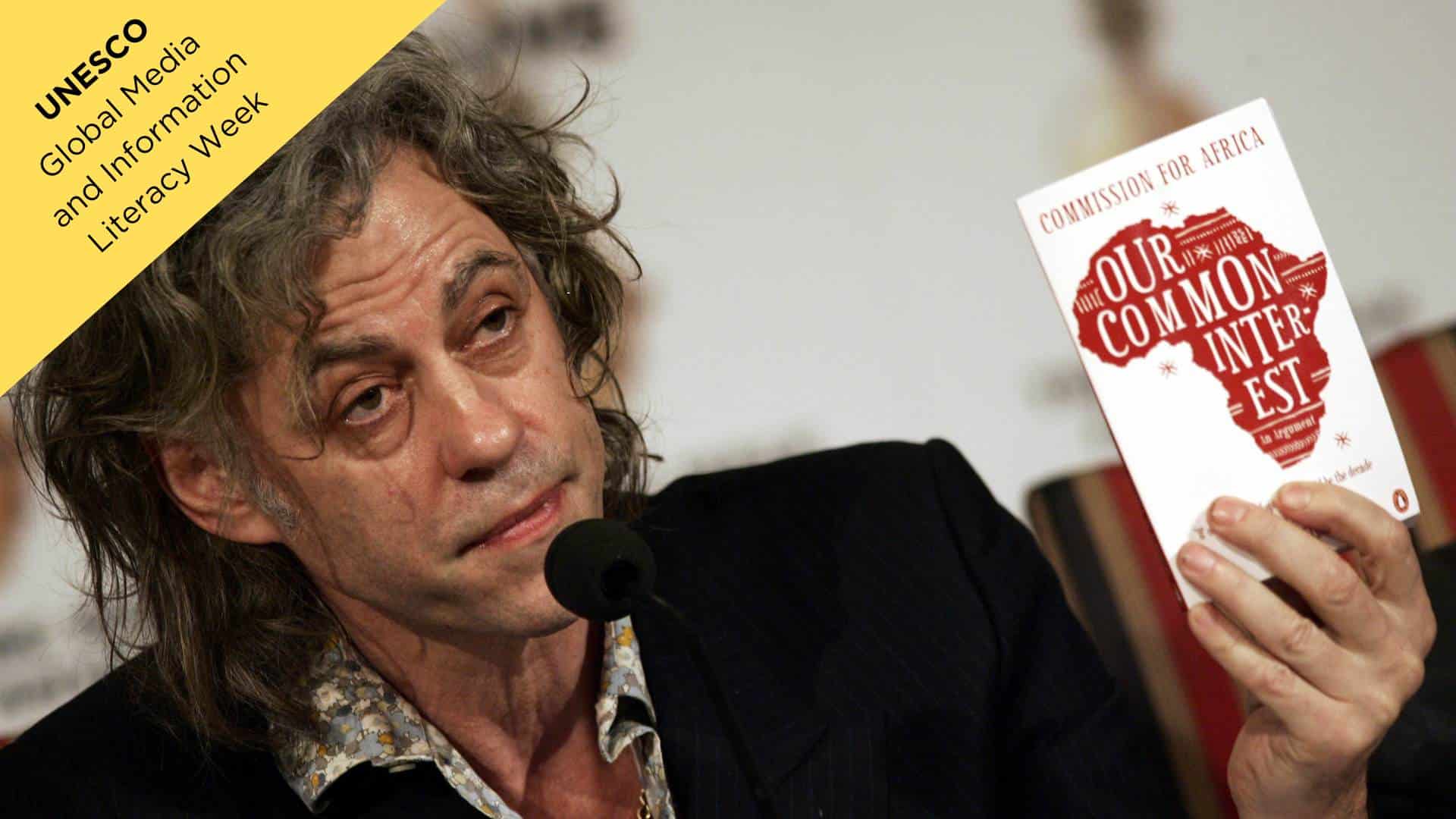

Bob Geldof, one of the original organizers of the ‘Live Aid’ concerts in 1985, displays a copy of the report by the Commision for Africa, during a news conference in London, 31 May 2005. (AP Photo/Lefteris Pitarakis)

From 24 to 31 October, the world marks Global Media and Information Literacy Week, an annual event first launched by UNESCO in 2011 as a way for organizations around the world to share ideas and explore innovative ways to promote Media and Information Literacy for all. For this year’s theme — “The New Digital Frontiers of Information: Media and Information Literacy for Public Interest Information” — News Decoder presents a series of articles and a Decoder Dialogue webinar on different aspects of media literacy.

We launched this series 24 October with a look at an effort in Finland to make media literacy a core component of primary education. Today, for our Friday Top Tip, we explore the concept of media framing and ways news can shape thought. On 28 October, we present a compilation of articles and other resources on media literacy. On 29 October we look at the role of artificial intelligence in disinformation with an article and a live Decoder Dialogue at 18:00 CET. It promises to be a lively online roundtable that will bring together experts and students from six countries to talk about the use of AI in schools. We end the series 30 October with an article on the use of labels to identify groups of people.

Back in 1940 researcher Paul Lazarsfeld surveyed voters and found that news media didn’t really affect how they would cast their vote. Instead, voters were more swayed by word of mouth and by people they trusted — opinion leaders like priests or teachers or celebrities.

So how, as a writer or media creator, can you affect how people think?

One way media holds sway, Lazarsfeld found, is when it influences the opinion leaders. In the 1980s rock musicians raised millions of dollars for famine relief in Ethiopia through the sales of the records “Do They Know It’s Christmas?”, “We Are the World” and the LiveAid concert. But that movement got started when rocker Bob Geldof saw a series of BBC news reports about the famine.

That got Geldof wondering what he could do and how he could get other people to care. The news reports alone didn’t do that. But by getting Geldof to care, they sparked a movement. These days we see this effect in the upcoming U.S. presidential election. When pop star Taylor Swift endorsed U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris for president, tens of thousands of “Swifties” registered to vote.

Another way media affects how people think is through “framing.” People weren’t caring about the famine in Ethiopia because few news outlets reported on it and when they did they portrayed or “framed” it as a problem too vast and too distant for most people to connect with.

Media framing

Let’s take a look at a current issue: The war in Ukraine. Many people outside of Ukraine care about what is happening there. Why? First, many different news outlets cover it. Second, the reports generally “frame” this complicated situation into something easy for people to understand: an underdog fighting for survival against a big bully. Most people are wired to root for an underdog.

The video of “Do They Know It’s Christmas?”

Often media frames stories and people around the idea of who to root for and who to fear. If the news pegs you as someone to root for — victims of hurricanes or wars for example — it can motivate support. If it pegs you as someone to fear — criminals or terrorists — it can spark anger or resentment.

We see this most clearly when some sides in a war are labeled freedom fighters or rebels, and others as terrorists or mercenaries.

We see it too, in portrayals of immigration. If you frame immigration as people fleeing dangerous situations to bring their families to safety you might get people to support it. If you frame it as people invading your country for jobs you will likely drum up opposition.

Where these messages are most effective is where different news media seem to frame an issue in the same way.

Framing the importance of a story

A third way media affects how people think is by determining the importance of an issue. If all the news media had made the famine in Ethiopia a top story, it would have sent the message that this was the most important thing happening in the world. That tends to garner attention. It spurs conversations and action.

If the news media completely ignores a famine, the message sent is that it doesn’t exist or it isn’t important. The topic doesn’t enter public conversations. If people dying in a hurricane gets more coverage than people dying trying to cross into the United States or on boats to Italy, people understand that hurricane victims are more important.

If wealthy people get more coverage than poor people, the media tells us that wealthy people are more important. Conversations will revolve more around topics that concern wealthier people — property rights, taxes, travel — than those that affect poor people — affordable housing, public transportation, universal healthcare.

That’s because news stories often form the basis of our conversations when we hang out with friends or relatives or when we chat and post our thoughts online.

So how do you get people to care about the story you write about or podcast on? Spotlighting it is the first step. People won’t care about what they don’t know about. Second, don’t over complicate it. While you don’t want to “dumb down” an issue, think about the ability of your audience to absorb information. Third, offer concrete ways people can get involved.

For many people, if they see a way that they could help, they will.

Three questions to consider:

- What is an “opinion leader”?

- Why do you think people might care about a tragedy happening in one place and not in another?

- Have you ever changed your mind about a subject because of someone you trusted?

Marcy Burstiner is the educational news director for News Decoder. She is a graduate of the Columbia Journalism School and professor emeritus of journalism and mass communication at the California Polytechnic University, Humboldt in California. She is the author of the book Investigative Reporting: From premise to publication.