Why do so many people believe ridiculous things? Maybe because they read these things over and over. Can we stop the spread of dangerous misinformation?

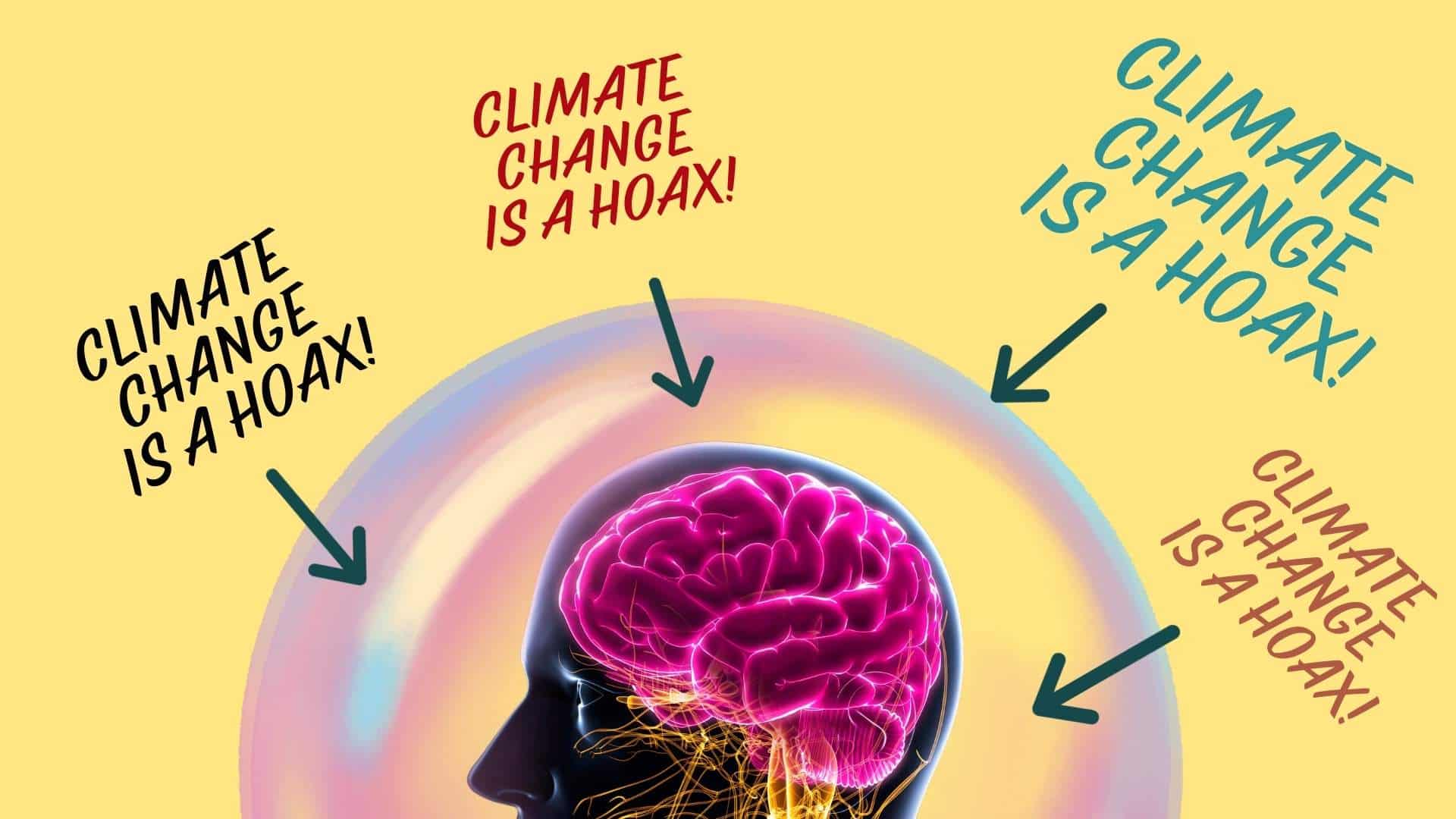

A man in a bubble hears repeatedly that climate change is a hoax. (Illustration by News Decoder)

Journalism and activism can be powerful tools for change. Each week in our News Decoder Top Tips, we share advice from reporters, editors, writers and master storytellers on ways to better engage audiences and spur change. In this Top Tip, Marcy Burstiner, News Decoder’s educational news director, explains the power of repetition in spreading disinformation.

Top Tips are part of our open access learning resources. You can find more of our learning resources here. And learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program or by forming a News Decoder Club in your school.

It is funny how something written a long time ago can be super relevant now. I’m talking about a book published more than 100 years ago: “Public Opinion” by Walter Lippman. It helps explain the power of political lies, which seem to flood our social media these days.

Lippman was a political commentator. In the book, he theorized that people create around themselves a pseudo environment — a bubble of information.

They start out as babies learning certain ideas, which form into a sort of a deflector shield, like the one on the Starship Enterprise.

From then on, ideas that contradict those first ones tend to bounce off the shield, while those that agree with it reinforce it, making those ideas even stronger. What becomes more frightening when it comes to falsehoods, especially things like racial stereotypes, is that when people learn information from multiple, different sources, they forget where they learned the information in the first place.

When that happens, they simply know it. It becomes fact.

Believing the ridiculous

That’s where the power of repetition comes in. You might read a post on X or Telegram that complains about all the crime caused by immigrants in your country. It seems to make sense to you so you don’t dismiss it. Then you hear someone on a podcast or a radio show complain about the same thing. Someone brings it up over drinks at a pub. And then you catch a local politician talking about it in a speech.

Multiple, different sources. In your mind it becomes fact that immigrants cause crime, even though data shows the opposite is actually true. Statistically, immigrants cause less crime.

Now if you are a careful listener and someone who is naturally skeptical, you might say: Hey! I wouldn’t have fallen for that misinformation in the first place!

But often lies are buried in lies. And a clever propagandist will camouflage some dangerous lies under more sensational, attention-grabbing lies. So in a speech about immigration, you might be so shocked to hear that immigrants eat neighbors’ pets — an absurd idea flying around the United States these days — that you say, “I don’t believe that!” Your conscious mind focuses on that disbelief of the ridiculous. But the other stuff in the speech, about immigrants causing crime, your brain doesn’t bother refuting because it isn’t paying as much attention.

That kernel of misinformation sneaks in past your brain’s deflector shield. And then when you hear it again, it is as if the new repetition confirms what you already heard. Soon what you heard becomes what you know. And it is difficult to convince someone that what they think they know is not true.

Where did you get that?

All of this is magnified when the information comes from a source you admire. That could be a friend, a relative, a teacher or a media star. You don’t want to believe that someone you like and trust is wrong or will lie to you. So unless it is disproven, you will tend to believe it.

But some lies are really hard to disprove. It is difficult to debunk what doesn’t exist. How do you prove that dogs aren’t being eaten by neighbors?

There is a but to all of this. Lippman said that as strong as the pseudoenvironment was — that deflector shield around us bouncing back ideas that conflict with what we think we know — there is something more powerful. That’s direct experience. In journalism school we said if someone tells you the sky is blue, see for yourself.

So you might think from all that you hear and read that homosexuals are depraved people. Then you meet someone who is gay, who is considerate and funny. A whole lot of the power of the misinformation about gay people fizzles.

That’s why, back in the 1970s, when California voters were going to the polls to vote on a measure that would have banned gay people from working in public schools, Harvey Milk, one of the first openly gay politicians, told the LGBTQ community that they all had to “come out” and publicly announce their homosexuality. He knew that if people recognized that that guy they worked with or went to school with or played softball with was gay, they would no longer be able to believe the lies.

Base what you know on facts.

In this Internet age we live in though, we are each having fewer direct experiences. We spend more and more time online having mediated conversations. Our friendships are digital and we play sports online instead of on the field.

A friend recently came back from a trip to Paris. We asked if he’d been to the Eiffel Tower. He said, “Better!” It turned out he visited a virtual reality place in Paris where, with a VR headset, he could fly around the Eiffel Tower. In his mind, the mediated experience was better than the real thing as he didn’t have to wait on line to experience it.

This is why fact-based reporting is so important. People need to see and hear the difference between ideas that have no basis to them, and those that are based on fact. But the sources of those facts need to be in those stories.

Propagandists who know what they are doing accomplish something else even if a particular falsehood doesn’t stick. Pour enough falsehoods into the information ecosystem and people get exhausted. It takes brain power and energy to sift through misinformation to get to verifiable fact. Most people don’t have the time, energy or attention for that.

They default to skeptism and decide to believe nothing they read or hear. That leads to apathy and the feeling that civic participation it is a waste of time. A lack of citizen activism allows those in power to pass legislation and adopt regulations that benefit whatever class of people they belong to or are beholden to.

Trace back information to its source.

So how to fight all this power of lies and repetition of falsehoods? By asking yourself this simple question and asking people who tell you things the same question: Where did you learn that?

Try to trace back the source of it. If you can’t, you should probably question it. Be skeptical. And when you first learn of something, keep in mind where you got it. Was it a reputable source? Was it based on fact or someone’s guesswork or wishful thinking? How would that person or media outlet know? Did any of the people reporting the information in the first place, experience it first hand? Were they there when it happened? Are they basing their ideas on data collected by a reputable organization?

Repetition can be a good thing. Its power of reinforcing an idea works when drafting an article or essay. Repeating phrases reminds readers or listeners what you are talking about so they don’t get distracted and confused.

But make sure you don’t repeat stuff that you haven’t confirmed, that you think you just know, that you think is fact. And if you want to know more about how to fact check ideas, check out this tipsheet by correspondent Norma Hilton. The danger of repeated misinformation will get worse with the proliferation of artificial intelligence as bots might give more weight to ideas that appear more often in the digital sphere.

Not all information is bad. Facts are out there. While virtual reality might be super cool, we need to ground ourselves in actual reality to solve problems in our communities.

Three questions to consider:

- What did Walter Lippman mean by a “pseudo-environment?

- How can an idea repeated gain strength even if not true?

- Can you think of something that you know but that you don’t know how you know it?

Marcy Burstiner is the educational news director for News Decoder. She is a graduate of the Columbia Journalism School and professor emeritus of journalism and mass communication at the California Polytechnic University, Humboldt in California. She is the author of the book Investigative Reporting: From premise to publication.