Sometimes we feel compelled to share or repost what we read. But when we do, we might unwittingly spread disinformation. Beware of “copypasta.”

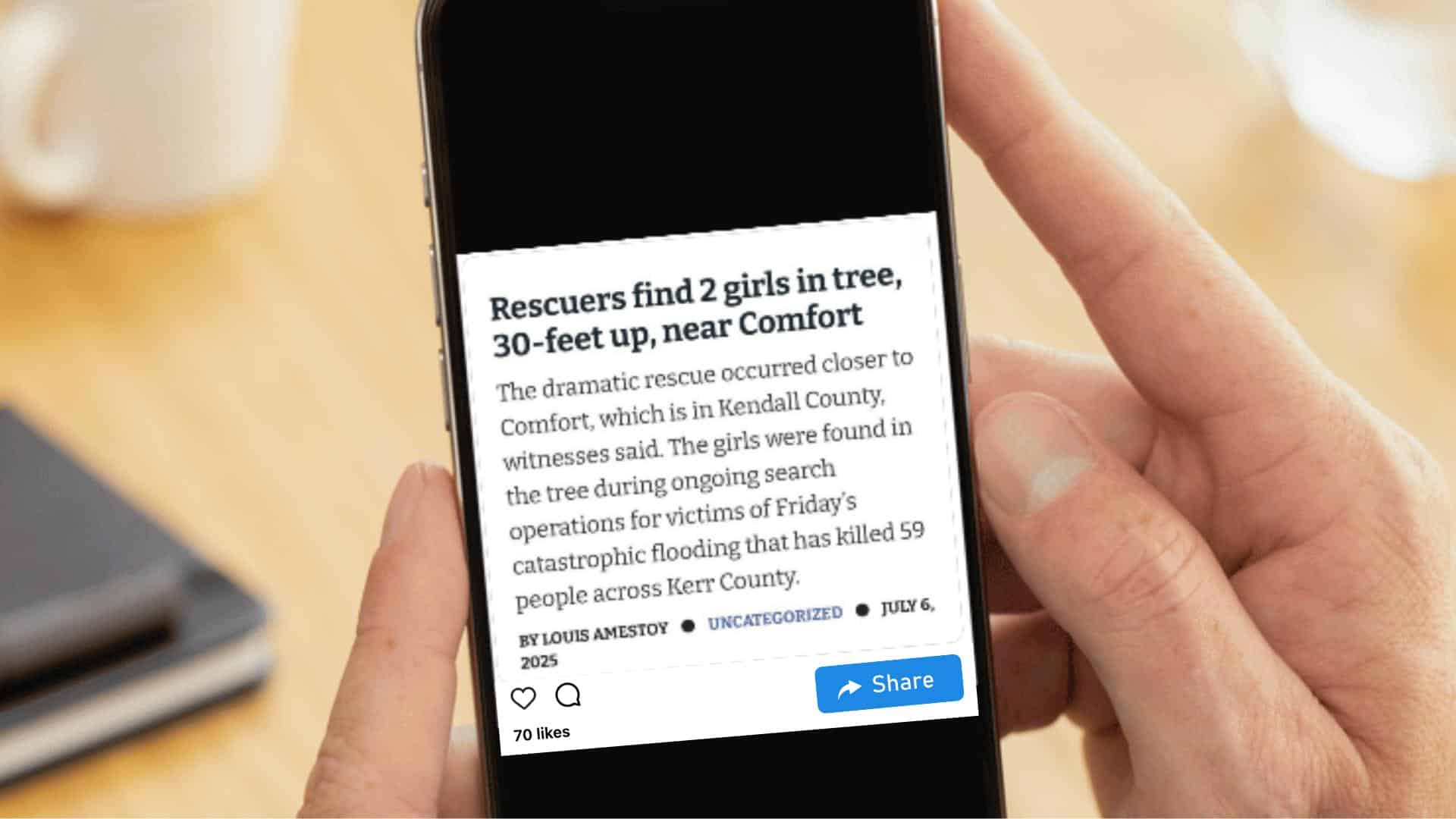

A phone with a copypasta post on it. (Illustration by News Decoder)

This article was produced exclusively for News Decoder’s global news service. It is through articles like this that News Decoder strives to provide context to complex global events and issues and teach global awareness through the lens of journalism. Learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program.

In the wake of the floods in the U.S. state of Texas earlier this month news circulated on social media of two girls being rescued. One of the first posts sharing the story included a screenshot of a post to social media that read:

Rescuers find 2 girls in tree, 30-feet up, near Comfort

The dramatic rescue occurred closer to Comfort, which is in Kendall County, witnesses said. The girls were found in the tree during ongoing search operations for victims of Friday’s catastrophic flooding that has killed 59 people across Kerr County.

A Facebook search of the post’s keywords returned dozens of identical or similarly-worded posts retelling the harrowing rescue. Other versions of the story were also shared across social media platforms like Instagram Threads, as well as in now-deleted articles across various news outlets.

But the story was fabricated.

It was a prime example of a type of misinformation known as “copypasta.”

Inciting fear

Social media posts that utilize copypasta — a portmanteau of “copy” and “paste” — are often used to incite fear or evoke emotions, prompting users to like and share the content. These posts are used for various reasons, whether to polarize different political groups further or to attract a broader audience and spread misinformation.

Alex Kasprak is an investigative journalist who reported for the digital fact-checking website Snopes for nearly a decade. In his experience, Kasprak says copypasta plays a central role in online misinformation. (For more on Snopes’ take on copypasta, head to this link.)

“The simplest way to put it, is that copypasta is a text that you see that is identical or nearly identical posted either with somebody’s name as an author or without it in an identical form on multiple posts such that it’s clear that whoever is posting it copied it from somewhere else,” said Kasprak.

“What you end up getting in that sort of phenomenon is a game of telephone.”

Copypasta serves as a new-age version of chainmail, seen in the early days of email, which promised good luck for forwarding a message or foretold misinformation if you let the email sit in an inbox.

Lacking credibility

In the case of copypasta, social media users are encouraged to comment, share or tag their friends in a post to boost engagement. Such emotion-evoking messages can serve as an entry point into more polarizing content, which is often rife with false information.

To identify copypasta, look for signs of vague or generic information that lacks a credible source or call to action. The way a post is written can also serve as an indication that it may be a copy-and-paste text.

“With copypasta, everything generally kind of travels forward, including errors in grammar or mistranslations,” Kasprak said. “If there are weird sentences that just kind of end or don’t fully make grammatical sense, that is an indicator that the tone of the message doesn’t match.”

If the post is shared by someone that you know on your feed, but the tone is different than how they usually post or talk, the content likely originated from another source — credible or not, Kasprak said.

In addition to spreading false information, copypasta can be used as part of bigger campaigns to push particular sentiments or ideologies. For example, back in 2017, U.S. government officials found evidence that Russian “trolls” took to social media and also deployed social media campaigns to connect certain users to various organizations or movements.

Danger to the infosphere

During these online campaigns, nefarious actors meddled in the election by posting emotional content to get users to engage, gradually bringing them down a digital rabbit hole of more polarizing issues.

Kasprak adds that copypasta content also harms the “infosphere,” or public knowledge otherwise rooted in fact. When copypasta becomes widespread and is presented as a “pseudofact,” people begin to cite it as common knowledge. A commonly held belief that many people cite as fact, for example, is that a mother bird will abandon its offspring if a human touches it. Experts agree that this notion is not true.

Another tactic behind those who post copypasta is to poison AI models in a similar way that fake news websites do. When enough content on the internet makes a particular claim, AI technologies may focus on this noise and refer to it as fact. In this way, AI programs are “trained” to focus and “believe” those posts over other sources of information.

Emotion-evoking posts may also fall into the copypasta category if they are not rooted in unbiased facts. If emotional language used in the post immediately sparks anger, sadness or another strong emotion, it may be a fake post.

“In general, the big thing to watch out for is if something fits perfectly into your notion of how the world works,” said Kasprak. Posts that validate a person’s view of the world or evoke strong emotions in a positive or negative way are more likely to be a red flag.

Kasprak advises users to check their biases when reading potential copypasta content; if something makes you angry or sad, double-check its source and legitimacy.

“Pause if you feel strongly about wanting to share something, because those posts are the ones where the risk of copypasta is higher,” said Kasprak. When he comes across a post he believes to be copypasta, Kasprak says that he tries to “tear apart” the argument, primarily if it supports his beliefs, until it dissolves.

“Check your blind spots and be vigilant in checking your work,” said Kasprak.

When in doubt, don’t share.

Questions to consider:

1. What is meant by “copypasta”?

2. How can something false become part of commonly believed?

3. Can you remember the last thing you reposted on social media? What kind of things do you share with your network?

Madison Dapcevich is a reporter who focuses on fact-checking scientific reporting, including marine and environmental issues and climate change. Her writing has been featured in Time, Lead Stories, Snopes, IFLScience, Business Insider, Outside, EcoWatch and Alaska Magazine, among others. Raised on an island in southeast Alaska, Madison is now based in the U.S. state of Montana.