Some 90 million students across the globe lose their access to education, not from snow or hurricanes, but from the political storms that rage around them.

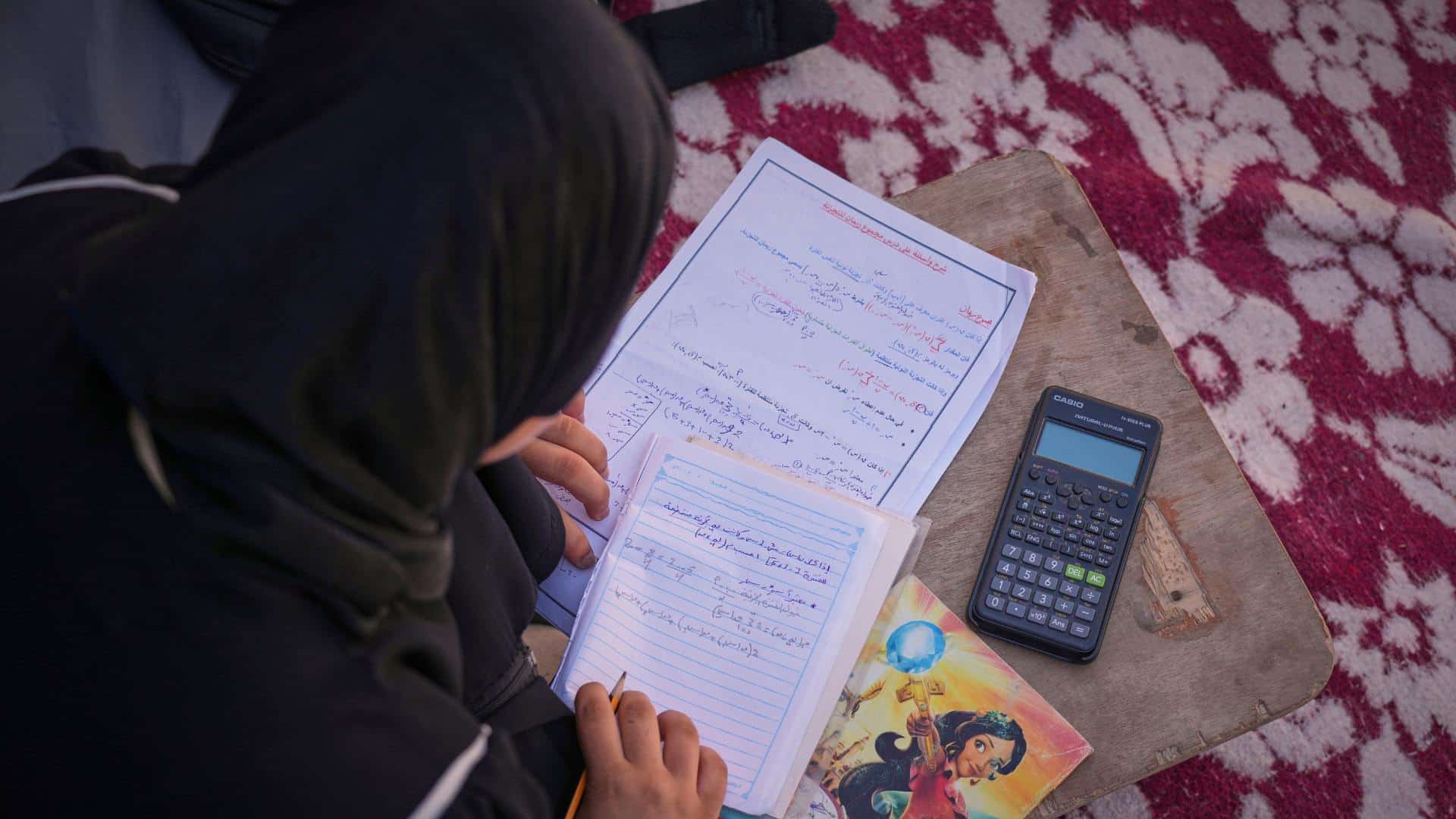

Sarah Qanan studies inside her family’s tent in the Gaza city of Khan Younis 28 June 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

This article was produced exclusively for News Decoder’s global news service. It is through articles like this that News Decoder strives to provide context to complex global events and issues and teach global awareness through the lens of journalism. Learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program.

Owais, a student in Srinagar, had been studying for his college entrance exam for two years. But when the day came to take the test, the roads were closed because of shelling between Pakistan and India. Srinagar is located in Kashmir, a region that has been claimed by both both countries. He couldn’t reach the exam center.

“It felt like my future was stolen by something I had no control over,” Owais said.

For decades, the relentless conflict in the Kashmir region has crushed the educational dreams of countless youth, ensnaring them in a cycle of violence and uncertainty.

Across the world, armed conflicts in places like Kashmir, Gaza and Ukraine, are systematically dismantling the infrastructure of education, leaving entire generations at risk.

The right to education has long been considered a fundamental right. The United Nations made it Article 26 in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted back in 1948.

But it seems to have little priority in today’s international conflicts and civil wars. A 2024 global study from An-Najah National University in the West Bank found that political violence disrupts education for 90 million students across 40 conflict-affected regions in the world.

Long-term costs of a crisis

The An-Najah study estimated that students in these conflict zones lose an average of 1.5 years of education, reducing their lifetime earning potential by 20-30%. This economic impact compounds the psychological toll, fostering a sense of hopelessness that spans borders. The global scope of this crisis is staggering.

The latest resurgence in violence in the Kashmir region began in April 2025, when militants ambushed tourists in the town of Pahalgam, killing 26 civilians — including one local pony ride operator.

That prompted India to suspend treaties and border crossings. In retaliation, India launched Operation Sindoor on 7 May targeting what was believed to be nine terrorist camps in Pakistan and Pakistan‑administered Kashmir.

Pakistan responded with heavy shelling, missile and drone strikes across the Line of Control, which serves as the disputed border between India and Pakistan, hitting homes, schools, religious sites and causing dozens of civilian deaths. The intense escalation subsided with a mutually agreed ceasefire effective 10 May.

In Kashmir, conflict disrupts education in two deeply damaging ways: first, shelling along the border destroys schools and displaces children; second, Kashmiri students living outside the region are often harassed and targeted simply for being Kashmiri and Muslim. Since Kashmir is India’s only Muslim-majority region, there is a perception across India that simply being Kashmiri links a person to militancy. As a result, Kashmiri students who live elsewhere in India often find themselves scapegoated.

Attacks outside of conflict zones

After major attacks — like the shelling in Pahalgam — students report being beaten, threatened or taunted by peers, vigilantes and sometimes even security personnel in cities across India. Consider the case of Saima, a young woman from Kashmir, who missed a critical interview in Delhi for acceptance into an engineering program not because of shelling, but because circulating videos of Kashmiri students being harassed terrified her.

Fearing for her safety, she asked for the interview to be conducted remotely but the university denied the request.

“Whenever incidents like the Pahalgam attack happen, Kashmiri students become the first targets outside Kashmir,” Saima said. “My generation witnesses everything — we go out to learn, but we become victims. Several of my friends left their education because of conflicts like stone pelting and curfews.”

Many of the students studying in Indian cities like Delhi and Bangalore end up returning home and abandoning their degrees.

“People look at me like I’m a threat,” said Zeeshaan, a Kashmiri student at a Delhi university. “I’ve faced taunts, and once, threats even at my hostel.”

This disruption in education caused directly or indirectly by armed international or regional conflicts occurs across the globe as the conflicts pushes students to foreign regions. A joint study by Cambridge University and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) found that the conflict in Palestine has created a “lost generation” of Palestinian youth, set back by up to five years in education due to trauma and lack of access.

Palestinian students abroad, for example, face similar xenophobia, with 32% reporting harassment linked to their identity, according to the An-Najah study.

Lack of teachers

In a May, the UNRWA reported in a post on the social media site X that 660,000 children in Gaza are out of school due to the war. The An-Najah study came to the same conclusion, finding that that 23% of Gaza’s schools have been destroyed since 2023, impacting 600,000 students.

Temporary schools in displacement camps in Gaza are woefully under-resourced, with only 15% of teachers trained to address trauma-induced learning gaps, leaving students like Fatima with little hope of resuming their studies. In Gaza, the ongoing conflict there has obliterated schools and shattered hopes.

In Ukraine, the war paints an equally grim picture. The World Health Organization reports that 3,800 educational institutions have been damaged or destroyed since the Russian invasion displacing 2.8 million students.

For those displaced to other regions, language barriers and social exclusion also push 45% of these students to consider dropping out. Many find themselves in regions, such as Russian-speaking areas, or countries like Poland, Hungary or Germany where Ukrainian is not spoken. In these host communities, the language barriers and cultural differences often lead to social exclusion, isolation and bullying.

The harm to education seems to be largely ignored by intervening governments. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), for example. found that just 3.5% of aid for Gaza has been invested in education.

“Major donors like the U.S. and Germany have neglected education in their aid packages and blockades continue to hinder the delivery of resources on the ground,” OCHA reported.

Questions to consider:

1. How can a war in a place like Kashmir affect students who study in places far away?

2. What is meant by a right to education?

3. How important is schooling to you and your family?

Tauseef Ahmad is a Delhi-based freelance journalist. He has worked with news organizations including The News International, Al-Jazeera, Article 14, Polis Project, Fair Planet and Mongabay. He tweets @wseef_t.

Sajid Raina is a Delhi-based freelance journalist and has worked with news organizations including The News International, Article 14, Diplomat, Fair Planet and Polis Project. He tweets @SajidRaina1.