To counter the lies slowing the fight against climate change and harming our democratic institutions will take a global effort. But people are mobilising.

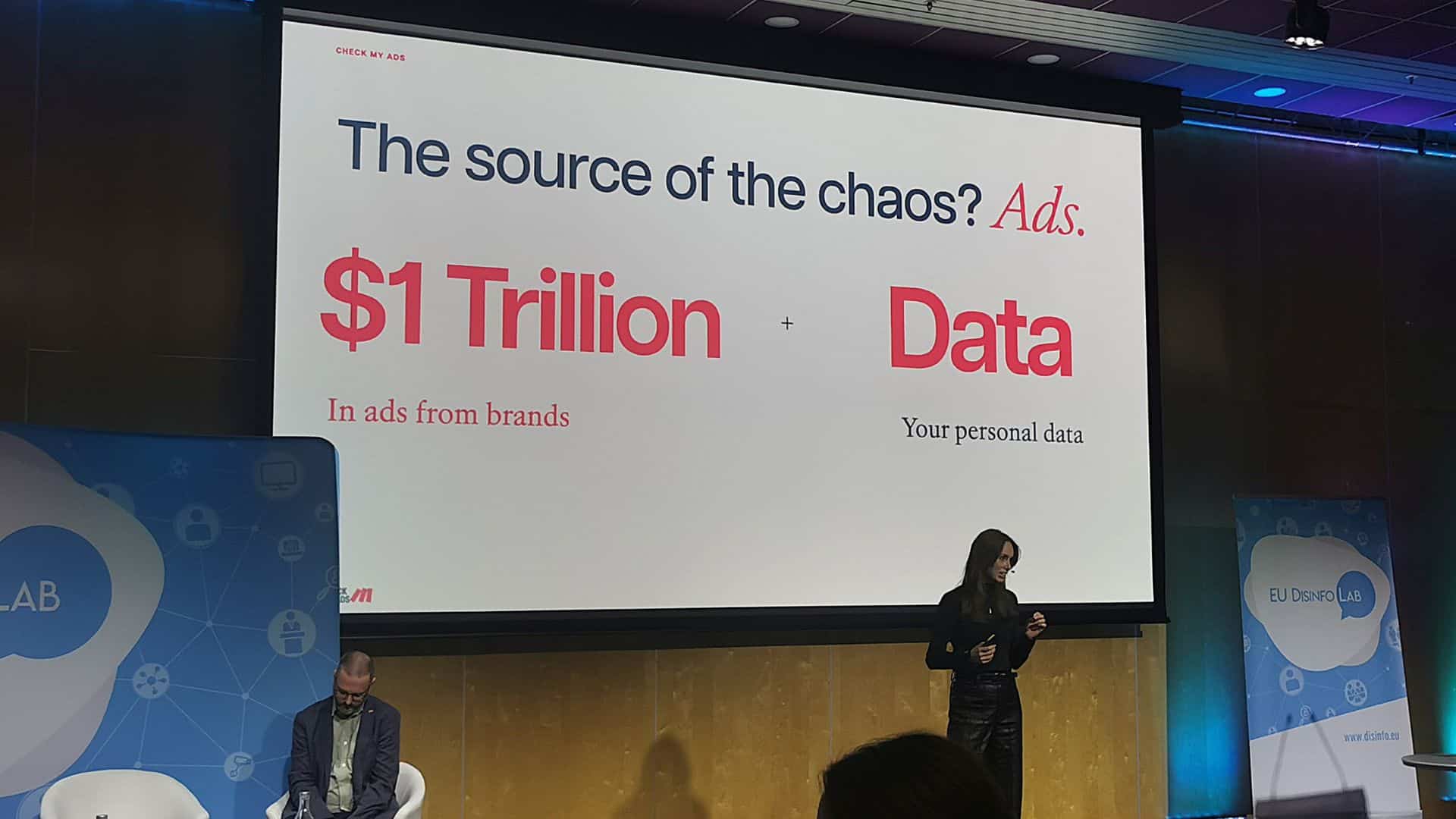

At the EU Disinformation Lab, Claire Atkin, co-founder of the ad industry watchdog Check My Ads, discussed ways her group and others are pushing the ad industry to become more transparent. (Credit: Sabīne Bērziņa)

Fighting disinformation is a never-ending game of whack-a-mole. But there is an army of people out there trying to do just that.

That’s what News Decoder learned last week at two conferences: The EU DisinfoLab in Riga, Latvia and the News Impact Summit in Copenhagen, Denmark.

There are hopeful solutions to online information manipulation. That’s what News Decoder’s User Experience Manager Sabīne Bērziņa learned at the EU DisinfoLab 2024.

Olha Danchenkova, a corporate PR specialist turned activist, told how even simple truths and solutions can easily get muddied in the fog of war and disinformation campaigns.

In the early days of the Ukraine war, the Russian government was spreading all kinds of misinformation about the conflict. In response, hundreds of communications professionals banded together — not just to get global society to pay attention, but to elevate fact-based information.

Danchenkova said the war forced people to be more inventive and collaborative and quickly come up with solutions that are practical and useful. One of their solutions — a database called Voices of Freedom and Truth — helps connect global organizations and media with trustworthy voices in Ukraine to make accurate and context-deep information easier to find than lies.

Taking on the advertising industry

Claire Atkin, co-founder of the ad industry watchdog Check My Ads, discussed ways her group and others are pushing the industry to become more transparent. Other industries face penalties for fraud. She argued that the advertising industry should also be regulated to combat fraud in the same way.

The way it works now, advertisers have little oversight of where the ads they want to place end up. That allows disinformation website owners to make easy money and means that advertisers are unknowingly funding these operations.

Atkin said that by making the trillion-dollar ad industry more transparent and accountable, we’d take the financial incentive away from the disinformation spreaders, she said.

Bērziņa said that there is still little in the way of systematic solutions to disinformation even though it is widley seen as a problem that threatens many democracies around the world. “Every individual is still largely responsible for learning skills that will help them differentiate between reliable and unreliable content,” Bērziņa said. “That’s why media literacy and fact-checking initiatives are as important as ever to help people understand how to do that.”

In Copenhagen, the News Impact Summit held by the European Journalism Centre, and supported by Google News Initiative, focused on fighting climate misinformation. The international news agency Agence France Presse (AFP), which has bureaus in some 150 countries, gave a crash course on fact-checking greenwashing — the corporate practice of trying to make polluters seem eco-friendly.

Sophie Nicholson and Ivan Couronne of AFP suggest different ways of combating this form of disinformation. It is important to understand the different ways greenhouse gas emissions are measured, they said, and to ask companies if their emissions target relies on carbon offsets, a practice that enables a business to pollute as long as it “offsets” its carbon by investing money elsewhere in a climate-friendly technology or organization.

The conference left News Decoder’s Climate Journalism Program Manager Amina McCauley inspired, particularly by a conversation on constructive journalism led by The Constructive Institute in Denmark. Danish media company Berlingske and Norway’s NRK argued that their readership is much higher for their constructive stories.

“The Constructive Institute describes the three main principles of constructive journalism to be solutions, nuance and conversation,” McCauley said. “So not just presenting a problem or a conflict, but presenting the possible solutions in a way that is not just black-and-white, while encouraging dialogue between the different perspectives.”

Educating youth to fight disinformation

Both fact checking and constructive journalism are key parts of News Decoder’s educational mission to foster global dialogue and cross-border connections. Bērziņa has been heading News Decoder’s partnership project with Sweden-based Mobile Stories — called ProMS or “Promoting Media Literacy and Youth Citizen Journalism through Mobile Stories” — to create an AI-powered tool to teach young people journalism. Fact-checking sources is an important aspect of the ProMS tool.

In its school partnership programs, News Decoder gets young people to learn how to tell fact-based stories. In doing so, they learn how to assess the reliability of sources of information.

McCauley has been heading News Decoder’s partnership with The Climate Academy, based in Belgium, on a project called Empowering Youth Through Environmental Storytelling, or EYES. The partnership has created educational modules schools can incorporate into their curriculums to teach climate change. McCauley is currently working to pilot the curriculum with eight schools in seven countries.

Fact-based storytelling is an important component of the climate modules. There is no better way for young people to understand the difference between credible information and disinformation than in researching and reporting their own stories on issues they care about, said News Decoder’s Educational News Director Marcy Burstiner.

“We want to arm teens with the skills and knowledge to spot disinformation,” Burstiner said. “But as important, we want to train a new generation of people to care about the quality of information they transmit to others — in stories they tell, in social media posts they create and in conversations they have.”