In the run-up to the UK elections, young people in Britain struggle to know where to turn. Their voice counts but does anyone listen?

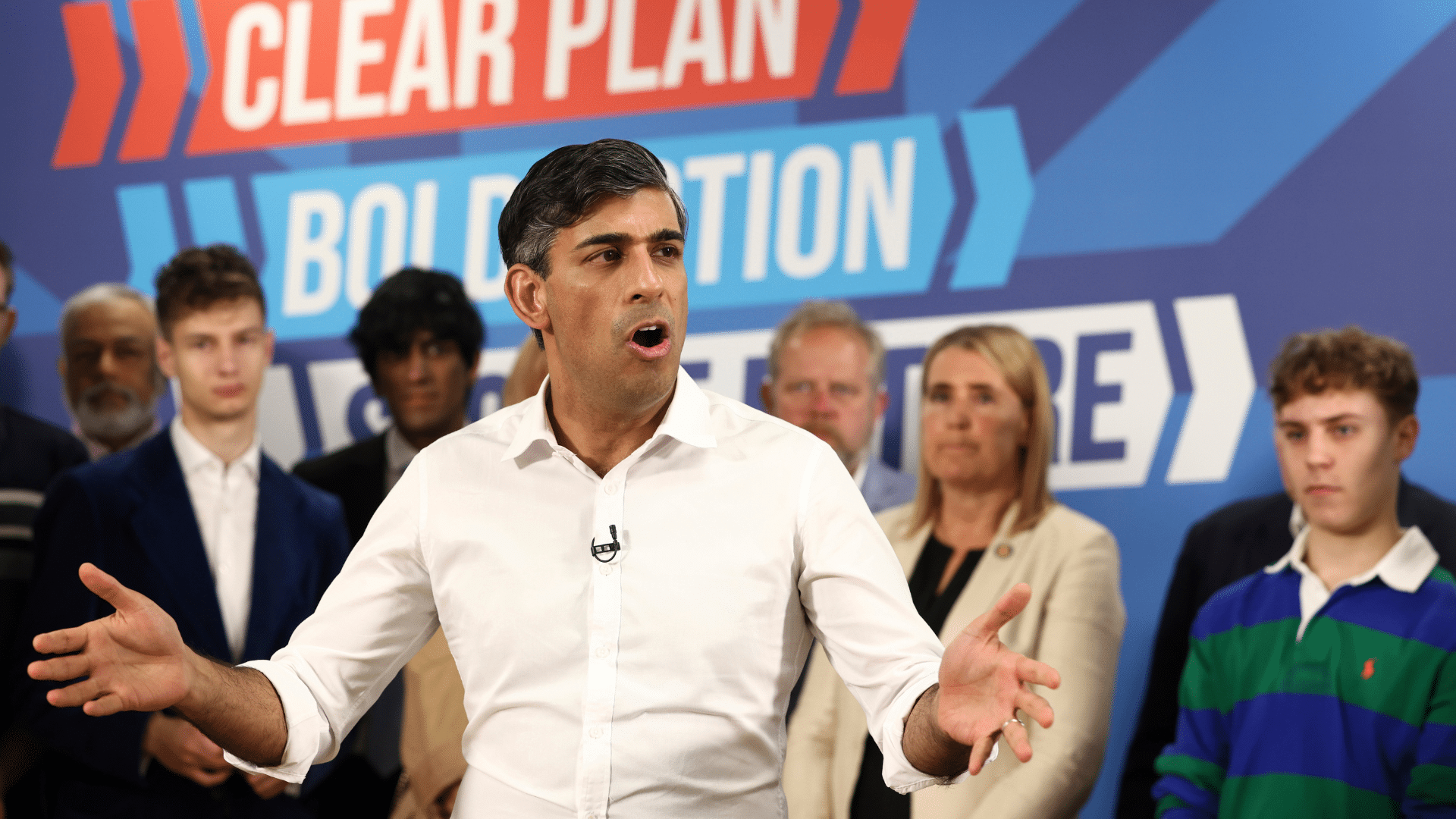

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Conservative Party leader Rishi Sunak delivers a speech as part of a Conservative campaign event in the build-up to the UK general election on 4 July in Leeds, England, 27 June 2024. (Darren Staples/Pool Photo via AP)

“Are you two really the best we’ve got?”

The question was posed by an audience member during a recent TV debate between Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and leader of the opposition Labour Party Sir Keir Starmer. And it captures much of the national mood as the United Kingdom heads to a general election on 4 July 2024.

Labour have had a steady 20-point lead in the polls since late 2022 and is expected to win with a comfortable majority. But up and down the country, there is a sense that a Labour victory will be more about ejecting the Tories, who’ve been in government for 14 years, than a positive endorsement of the opposition who have failed to inspire ‘massive enthusiasm’ among the electorate.

“During the Tony Blair election of 1997 there was a spring in people’s step,” said Harvey Morris, a News Decoder correspondent who was parliamentary correspondent for Reuters during the Thatcher era. “An unpopular Tory government was being thrown out; the economy wasn’t too bad. It was quite a time to be around. There is none of that this time.”

Indeed, this election is taking place during one of the bleakest economic periods in recent UK history. The past decade and a half has seen the worst income growth for generations. House prices are currently higher relative to earnings than at any time in the last 148 years. The negative economic consequences of Brexit are becoming increasingly apparent.

Nine years of austerity followed by Covid and the global energy crisis have pushed 7.2 million households into food insecurity. There are a near-record 7.57 million people on waiting lists for treatment on the National Health Service.

Difficult times for young people

It is the youngest generation who are being hit the hardest.

“There’s a cost-of-living crisis, a renting crisis, a housing crisis, an energy crisis, a welfare crisis. So many crises,” said Cecilia Jastrzembska, president of the Young European Movement UK. “I know a lot of young people who are insanely qualified but can’t get an interview despite sending out five applications a day and reaching out to all their contacts.”

However frustrated they may feel, the ballot box is not where the UK’s youngest voters have tended to seek change. The UK has one of the lowest youth turnouts for general elections among OECD countries. Only 47% of 18 to 24-year olds voted in the 2019 general election and the rate has been below this since the late 1990s.

Compare this to the 66% of the same age group who voted in the 2017 Netherlands general election or the 68% who turned out for the German federal election the same year.

There is no evidence 2024 turnout will be any better, and there are signs it may be worse. Registrations by the under 25s in the run up to this election were half the amount recorded prior to the 2019 election. One poll suggests turnout across all age groups may hit a record low.

“Practical challenges are important,” said Markus Wagner, a professor at the University of Vienna specialised in electoral behaviour. “Young people move more often, so that they might be registered where they are living, and they might often be abroad as well. Because they are less settled, they might feel less attachment to their area and less involved.”

Youth feel disenfranchised and disengaged.

The unusual decision to hold the election in July during university holidays, plus the recent introduction of compulsory voter ID could add logistical obstacles for some young voters.

But the number who face practical challenges is likely to be dwarfed by those who simply won’t vote.

“A lot of young people feel really disenfranchised and disengaged,” said Jastrzembska. “I know a few people who haven’t bothered to register. There’s an overwhelming sentiment that the parties don’t represent their interests, that politics is governed by old white men and that their priorities don’t match with young people’s aspirations or needs.”

Wagner agrees. “Young voters do tend to get ignored by parties,” he said. “Parties know that younger voters are less likely to vote, and there are far more pensioners than voters under 25. So that is where parties’ focus lies. Parties also have a hard time tailoring their message to young people and finding ways to be appealing and interesting. They would rather spend their energies elsewhere.”

Meanwhile, the far-right Reform UK party has tried to court a younger vote, but — unlike its equivalents in other parts of Europe — is failing to make significant in-roads.

Morris points to historical reasons. “The whole idea of the far right has not been so fashionable as on continental Europe,” he said. “Young people see their contemporaries who are attracted to the far right as out of it and a bit weird.”

Far from trying to appeal to the youngest voters, the UK’s mainstream parties have often appeared at best indifferent to young people, at worst hostile. The Conservatives, in particular, have done more to alienate than attract young voters in recent years by stoking so-called ‘culture wars’, taking a hostile stance to ‘remoaners’ who voted against Brexit (as most young people did) and recently proposing the introduction of compulsory military service. As a result, the Tories’ projected share of the under-25 vote has fallen to just 4%. Even Young Conservatives are feeling disillusioned by their party.

Labour, too, are “not bending over backwards to reach young people” said Morris, perhaps complacently assuming they don’t need to make much effort with a constituency that has always tended to lean left.

A context of political instability

The jockeying of political parties is happening in the context of the pronounced political instability of recent years and an erosion of trust in the political system. Both have contributed to a disengagement from politics by voters of all ages, not only the young. For many, there is a sense that the system is broken and there’s no point in engaging with it. Trust in politicians is at a 40-year low.

GLOSSARY

Culture Wars: Cultural conflict between social groups and the struggle for dominance of their values, beliefs and practices.

First past the post: A ‘winner-takes-all’ voting system in which voters have a single vote and the candidate with the most votes wins.

Austerity: A set of political-economic policies that aim to reduce government budget deficits. Austerity measures implemented between 2010 and 2019 in the UK focused on reductions in public spending and tax rises.

Partygate: A UK political scandal about parties held by government staff that contravened the Covid-19 lockdown restrictions imposed on the country in 2020 and 2021. It led to the downfall of Prime Minster Boris Johnson after it was found that he had lied to Parliament about his knowledge of the parties.

Remoaner: A ‘Remain’ voter who complains about or rejects the outcome of the 2016 Brexit referendum.

Ned Holland is a 22-year old who works at a talent agency in London. “It’s been pretty messy in the UK,” he said. “We’ve had four prime ministers in five years. Boris Johnson lied about ‘Partygate.’ Liz Truss’ premiership was a disaster. The Tory party is divided by infighting.”

Many young people feel they don’t know enough about politics to make a voting decision. For those who do plan to vote, the choices can be confusing. With weaker party loyalties and greater volatility, the under 25s tend to leave voting decisions to the last minute. The UK’s first-past-the-post electoral system, which favours larger parties over small, can leave voters facing a dilemma, as Holland explains.

“The Green Party is probably most aligned to my views, but I don’t want to feel like my vote is being wasted,” he said. “Is it worth voting for a small party if it’s not going to win?”

Yasmin Laceyford, an 18-year-old student and first time voter from Bristol, is taking a more pragmatic approach.

“I’m basically choosing between four parties. They’re all looking a bit the same at moment,” she said. “I’m going to read the manifestos and ultimately vote for the one has the best plan that I think is the most realistic, i.e. that doesn’t make too many promises that I know they won’t keep.”

In terms of how young voters see the future beyond the election, Will Baylis, a 20-year-old student from London expresses a sentiment shared by many of his peers. “I’m excited to have an opportunity to exercise my vote for the first time,” he said. “But my prevailing feeling about the future is one of concern and trepidation.”

Holland agrees. “There are a lot of hurdles to tackle post elections,” he said. “There are difficult decisions to be made and not everyone is going to be happy about them. But it’s definitely time for a change. Hopefully what’s coming will be better that what we have now, but the proof will be in the pudding.”

Three questions to consider:

- What is different now in UK politics compared to in 1997?

- What are the reasons keeping British youth from voting?

- How do young people feel about UK politics?

Thea Lacey is News Decoder’s Director of Development. She has 15 years of experience managing fundraising and programmes for mostly humanitarian and development NGOs, both small and large, including five years based in West and Central Africa. She holds an undergraduate degree in Politics from the University of Edinburgh and a postgraduate degree in International Development from SOAS University of London.