After massive floods in Valencia, fake news messages on the internet seemed targeted to intensify chaos and undermine trust in the authorities.

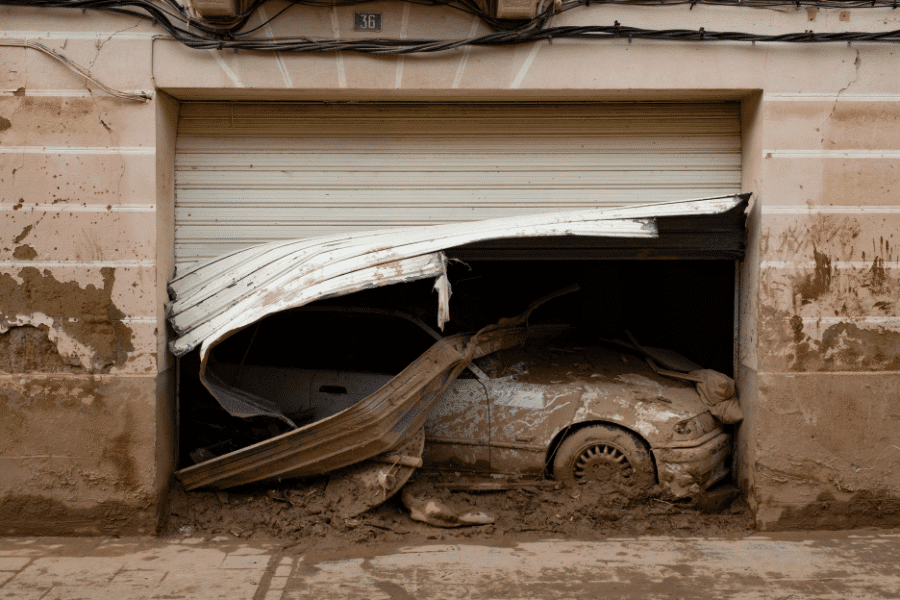

A mud-covered car in a garage destroyed by floods in Valencia, Spain in November 2024. (Credit: Eline van Nes)

This article was produced exclusively for News Decoder’s global news service. It is through articles like this that News Decoder strives to provide context to complex global events and issues and teach global awareness through the lens of journalism. Learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program.

Lourdes Donat (standing) and Cello Herrero look out into the street full of mud and debris, two weeks after the flooding. (Credit: Eline van Nes)

The street in front of Lourdes Donat’s house is accessible again, but it still looks like a disaster zone.

There are two crumpled cars, the windows shattered, full of mud. The shutters of the store opposite are dented, the sides of the roads are piled with trash: reeds, wood, garbage, everything smeared with mud.

Donat, 52, feels sad and tired as she looks at it with her sister-in-law Cello Herreros. On their phones they show images of the same street after the disaster that flooded Valencia at the end of October and took at least 223 lives. On one video, cars are piled on top of each other, on another the street has turned into a roaring river. Herreros points.

“There, they found two bodies in a garage that had flooded,” Herreros said. “And there was a pile of rubbish, in which they found a body days later. On the other street they found two people in a car, drowned.”

The two women shake their heads. In all the fear that clearly still has shaken them, they agree on one thing: they do not believe the official death count.

“If we have five bodies in this street alone, and the disaster hit several towns, it just can’t be true,” Herreros said.

Social media intensifies fear.

With the flood in the streets came a flood of disinformation passed through social media accounts. One of the main themes in all these messages on platforms like X and Telegram, is the death count. According to messages, for example, in one underground parking garage under the Bonaire mall alone there would have been hundreds of bodies.

A tree remains standing by itself amid the mud and debris left after floods in Valencia in November 2024. (Credit: Eline van Nes)

An audio message that was widely shared from what was supposed to be a sergeant of the Spanish military emergency service said there would be 200 dead children.

Later, when the fire brigade pumped out the water from this parking garage, they did not find any bodies in the cars that were left there.

“I don’t know anymore,” Herreros said. “I just stopped watching the news. It’s all too much for me. All I know is that the politicians failed us, for the rest I don’t know what is true. They alerted us too late, that’s for sure.”

She thinks that Carlos Mazón, the regional president, should be jailed. Donat agrees with her.

“They had plenty of time to warn us about the water, but they didn’t,” Donat said. “Now I lost everything. My house is ruined, my car gone.”

Disasters natural and man-made

Heavy rainfall surprised local authorities in Valencia and turned into a flooding disaster that is one of the biggest Spain has known in recent history. Two weeks later, the disaster area is still recovering and street after street is still full of crumpled cars and mud. Slowly a timeline of the events is getting clear, in which it is seen that the local government did not take weather warnings seriously enough until it was too late.

Talking to people in this area, it quickly becomes clear that many believe in fake stories that have been spread during this chaos.

These are not only about the death toll — a recurring story is about a dam that was opened erroneously, thus causing the floods. This story was discredited by Spanish factchecker Maldita, showing the dam was in another river.

Another online story blames cloud seeding gone awry, in which humans have tried to seed rain which would have caused the unprecedented rainfall in the area. A recurring theme in most stories is a government coverup of the lack of disaster preparation.

Lies and truth

Most stories are based on some truth. The cloud seeding, for instance, refers to Morocco recently investing millions of dollars in this technology to make rain fall over agricultural areas. Maldita showed that the technology could not cause the weather event in Spain.

Some truth is also at the heart of the posts that argue there was a government coverup.

Crumpled, mud-covered cars line a street after floods in Valencia, Spain in November 2024. Credit: Eline van Nes

When lies are partly true

Mazón was having a long lunch with a reporter when the rainstorm grew into a catastrophe, and later insisted he was back at the office.

“It’s very difficult to get to the source of the messages,” said Ximena Villagrán, of Maldita. “Therefore, it is difficult to know exactly why they are made. We know there are different motivations. Economic reasons, for instance, since you can make money with content on X. But there are also messages that are really directed to undermine trust in government.”

After the flooding, Maldita tirelessly fact checked messages that appeared on the internet, for example in an article headed: “The 20 hoaxes surrounding the parking under the mall.”

Two weeks after the disaster, Villagrán can divide the fake messages into several subject categories: the number of dead, NGOs making money with donations or undermining trust in police and government. In this last category, Villagrán said, they could see many Russian information channels involved — not to say they were created by Russians, but they were certainly shared by accounts and channels which previously had shared disinformation surrounding the Ukraine war.

The amount of disinformation flooding the internet about the disaster in Valencia is unprecedented for Spain. Internationally it is comparable to the days after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia.

“In Spain, only in relation to the pandemic have we seen something like this,” Villagrán said.

How disinformation spreads

As before, Maldita could connect similar dots this time; many people or accounts which shared disinformation about the pandemic, now shared specific messages about the disaster.

In this category of messages, it is about the government using disasters — or even creating them with cloud seeding or other technology — to be able to control the population by fear and crisis measures.

“Much of these are aimed at science,” Villagrán said. “It is good to doubt and to criticize, but what these messages are aimed at is often to undermine things that have already been proven in science.”

For Maldita it’s clear that much must be done to make people more media literate and prepared for such an explosion of fake news.

They push for more teaching on the subject in schools. But also, Villagrán points out, elderly are a group that is particularly susceptible to these kinds of messages. They are used to reading newspapers from when they were young, so now they find it more difficult to recognise an article with false information, especially when it does have the make-up of an official news outlet — including the same kind of font and a logo.

Opportunities to create havoc

But mostly it is fear and shock that are the emotions that lower people’s filter in their ability to think critically. People simply start sharing anything they see, looking for an explanation for whatever has just happened to them.

Even if they know that not everything might be true, they want their loved ones to have access to all the information that is out there — especially when there is still a risk of further danger, such as during the outbreak of a war or a big natural event.

Raúl Magallón, professor of communication at Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, told Spanish newspaper El País that disasters are an opportunity for those who want to deliberately sow chaos. “Disinformation has more potential and is more effective in moments of uncertainty,” he said.

And uncertainty, that surely is visible in the streets of Valencia these days.

Two weeks after the flooding, teams — volunteers, firemen and military — are still cleaning up the streets from all the mud and debris. The government has made its first pledges to financially help people hit by the disaster, but those who have just lost their house, car or even a lost a loved one, don’t know if and how this help will actually come.

After showing how her house was affected by the floods, Cello Herrero stands at the front door again. She looks into one of the crumpled cars that is still standing in front of her building, and she describes how she was standing on the balcony of her house during the flooding. She saw people pulled away by the turbulent water that was gushing through the streets.

“I will never forget the screaming,” she said. “It’s the way they screamed. I just stood there, and I couldn’t do anything for them. I don’t even know if they made it.”

Cars are removed from a street after floods in Valencia, Spain in November 2024. (Credit: Eline van Nes)

Three questions to consider:

- Why do people turn to social media for information after natural disasters?

- Why is it difficult to discredit false information?

- How can you make sure that the information you read is reliable?

Jurriaan van Eerten is a Dutch writer and reporter. After having worked for years in Latin America and the United States, now he is based in Madrid, Spain, where he is writing his second novel. He works together with his wife, photographer Eline van Nes.

A great timely article about media literacy. It is unfortunate, however, that the questions to consider at the end are almost illegible with the grey text on a red background.

Thank you for your comment, and for drawing our attention to the problem. We’ve had technical difficulties with our website displaying some content properly, but hopefully the questions box is now corrected. – Maria, News Decoder