With AI taking over much of what we do, will people still value works created purely from one person’s brain? Is creativity worth anything anymore?

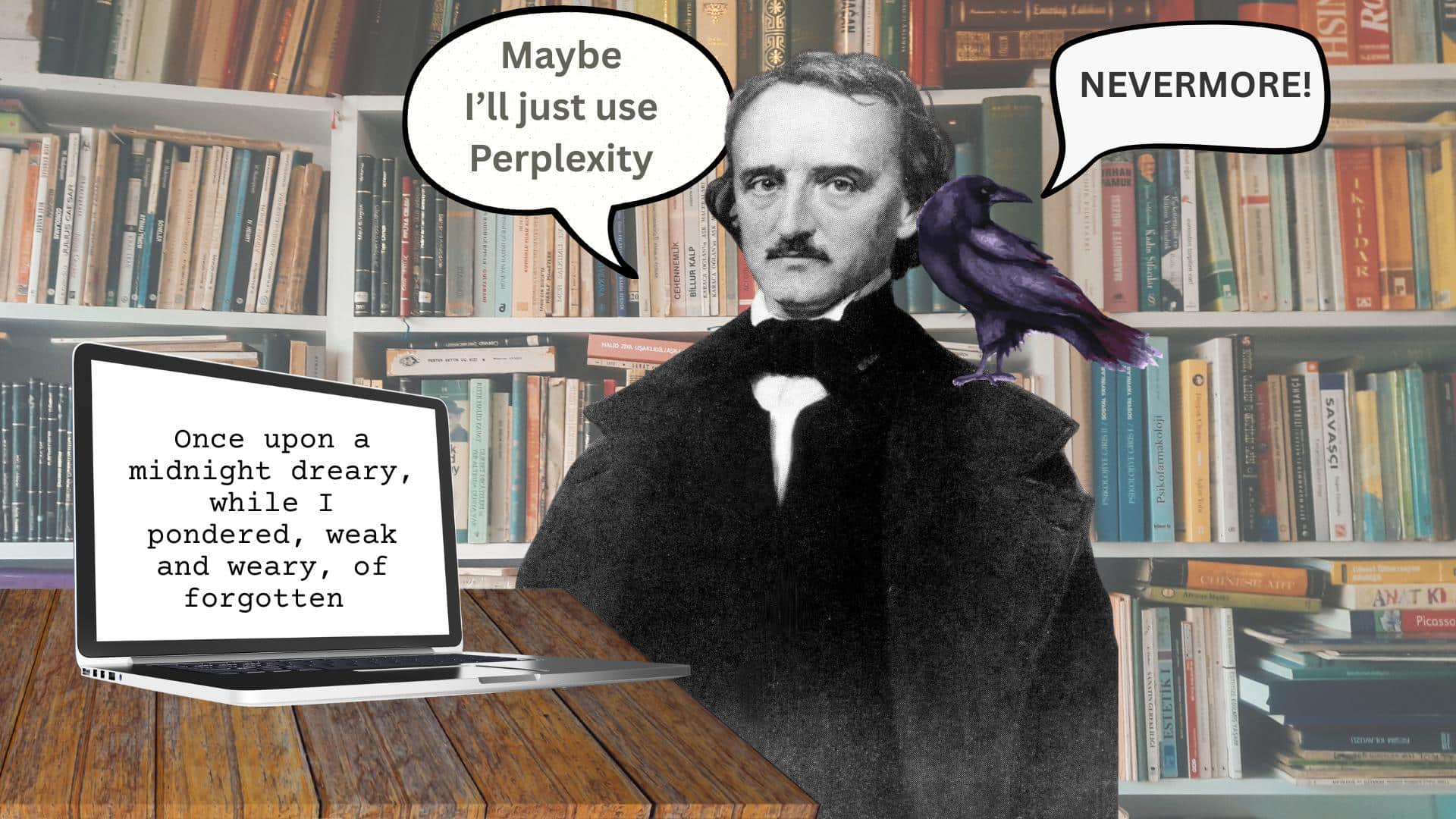

Edgar Allen Poe considers using AI to write a poem. (Illustration by News Decoder)

I have written the piece that you are now reading. But in the world of AI, what exactly does it mean to say that I’ve written it?

As someone who has either written or edited millions of words in my life, this question seems very important.

There are plenty of AI aids available to help me in my task. In fact, some are insinuating themselves into our everyday work without our explicit consent. For example, Microsoft inserted a ‘Copilot’ into Word, the programme I’m using. But I have disabled it.

I could also insert prompts into a service such as ChatGPT and ask it to write the piece itself. Or I could ask the chatbot direct questions and paste in the answers. Everybody who first encounters these services is amazed by what they can do. The ability to synthesise facts, arguments and ideas and express them in a desired style is truly extraordinary. So it’s possible that using chatbots would make my article more readable, or accurate or interesting.

But in all these cases, I would be using, or perhaps paraphrasing, text that had been generated by a computer. And in my opinion, this would mean that I could no longer say that I had written it. And if that were the case, what would be the point of ‘writing’ the article and putting my name on it?

Artificial intelligence is a real asset.

There is no doubt that we benefit from AI, whether it is in faster access to information and services, safer transport, easier navigation, diagnostics and so on.

Rather than a revolution, the ever-increasing automation of human tasks seems a natural extension of the expansion of computing power that has been under way since the Second World War. Computers crunch data, find patterns and generate results that simulate those patterns. In general, this saves time and effort and enhances our lives.

So at what point does the use of AI become worrying? To me, the answer is in the generation of content that purports to be created by specific humans but is in fact not.

The world of education is grappling with this issue. AI gathers information, orders and analyses it, and is able to answer questions about it, whether in papers or other ways. In other words, all the tasks that a student is supposed to perform!

At the simplest level, students can ask a computer to do the work and submit it as their own. Schools and universities have means to detect this, but there are also ways to avoid detection.

The human touch

From my limited knowledge, text produced with the help of AI can seem sterile, distanced from both the ‘writer’ and the topic. In a word, dehumanised. And this is not surprising, because it is written by a robot. How is a teacher to grade a paper that seems to have been produced in this way?

There is no point in moralising about this. The technologies cannot be un-invented. In fact, tech companies are investing hundreds of billions of dollars in vast amounts of additional computing power that will make robots ever more present in our lives.

So schools and universities will have to adjust. Some of the university websites that I’ve looked at are struggling to produce straightforward, coherent guidance for students.

The aim must be, on the one hand, to enable students to use all the available technologies to do their research, whether the goal is to write a first-year paper or a PhD thesis, and on the other hand to use their own brains to absorb and order their research, and to express their own analysis of it. They need to be able to think for themselves.

Methods to prove that they can do this might be to have hand-written exams, or to test them in viva voce interviews. Clearly, these would work for many students and many subjects, but not for all. On the assumption that all students are going to use AI for some of their tasks, the onus is on educational establishments to find new ways to make sure that students can absorb information and express their analysis on their own.

Can bots break a news story?

If schools and universities can’t do that, there would be no point in going to university at all. Obtaining a degree would have no meaning and people would be emerging from education without having learned how to use their brains.

Another controversial area is my own former profession, journalism. Computers have subsumed many of the crafts that used to be involved in creating a newspaper. They can make the layouts, customise outputs, match images to content, and so on.

But only a human can spot what might be a hot political story, or describe the situation on the ground in Ukraine.

Journalists are right to be using AI for many purposes, for example to discover stories by analysing large sets of data. Meanwhile, more menial jobs involving statistics, such as writing up companies’ financial results and reporting on sports events, could be delegated to computers. But these stories might be boring and could miss newsworthy aspects, as well as the context and the atmosphere. Plus, does anybody actually want to read a story written by a robot?

Just like universities, serious media organisations are busy evolving AI policies so as to maintain a competitive edge and inform and entertain their target audiences, while ensuring credibility and transparency. This is all the more important when the dissemination of lies and fake images is so easy and prevalent.

Can AI replace an Ai Weiwei?

The creative arts are also vulnerable to AI-assisted abuse. It’s so easy to steal someone’s music, films, videos, books, indeed all types of creative content. Artists are right to appeal for legal protection. But effective regulation is going to be difficult.

There are good reasons, however, for people to regulate themselves. Yes, AI’s potential uses are amazing, even frightening. But it gets its material from trawling every possible type of content that it can via the internet.

That content is, by definition, second hand. The result of AI’s trawling of the internet is like a giant bowl of mush. Dip your spoon into it, and it will still be other people’s mush.

If you want to do something original, use your own brain to do it. If you don’t use your own intelligence and your own capabilities, they will wither away.

And so I have done that. This piece may not be brilliant. But I wrote it.

Questions to consider:

1. If artificial intelligence writes a story or creates a piece of art, can that be considered original?

2. How can journalists use artificial intelligence to better serve the public?

3. In what ways to you think artificial intelligence is more helpful or harmful to professions like journalism and the arts?

Alexander Nicoll is a writer and former journalist. He reported for Reuters and the Financial Times from around the world and later was a writer and editor for a defence think-tank.