Meeting a growing energy demand can go hand-in-hand with the green transition. This is what India could show the world.

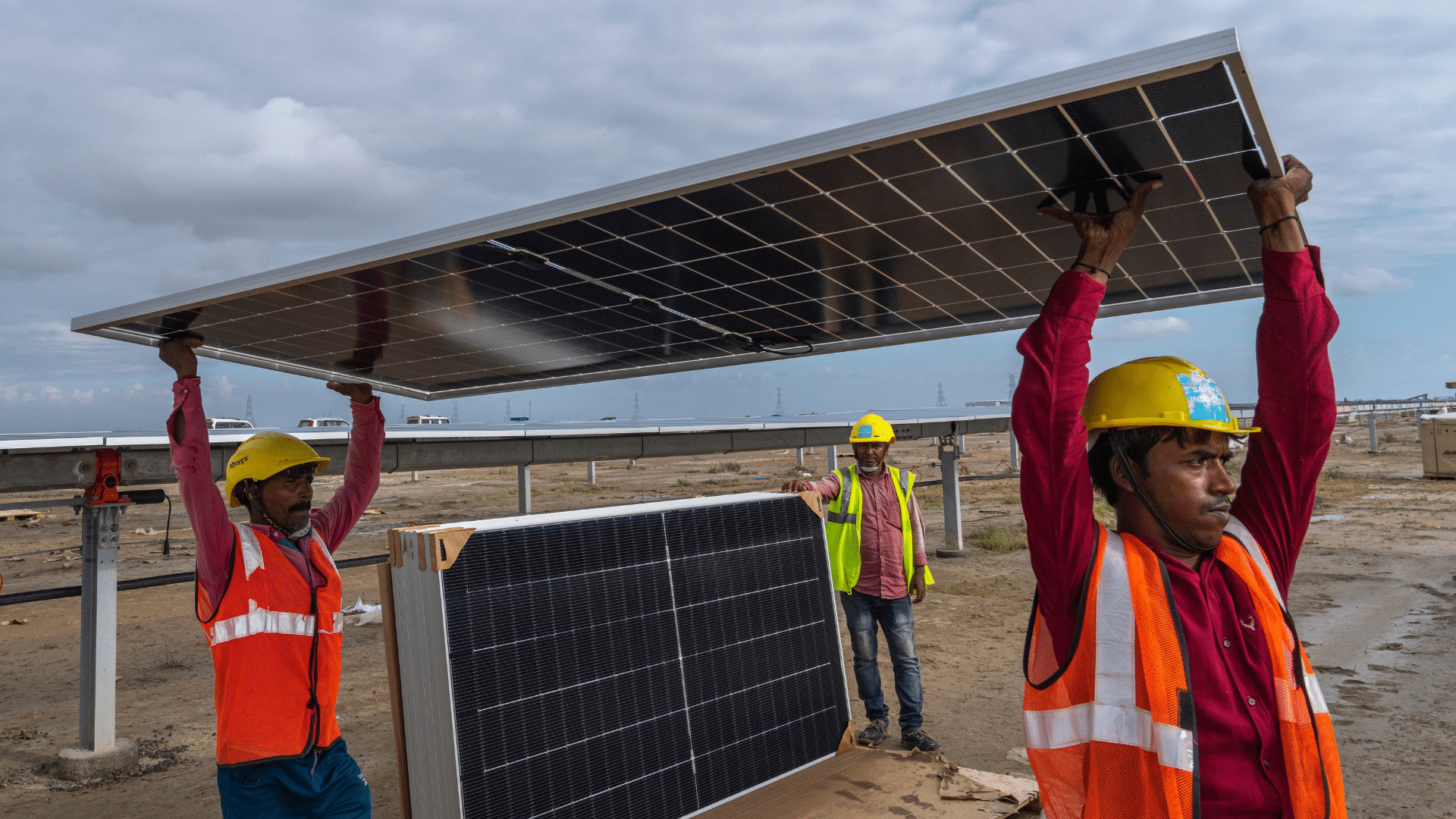

Workers carry a solar panel for installation at the under-construction Adani Green Energy Limited’s Renewable Energy Park in Gujarat, India, 20 September 2023. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool)

India has entered discussions to join the International Energy Agency (IEA) as a full member — a move that would recognize the world’s most populous country as a key player in tackling global energy and climate challenges.

If successful, India would become the first country from outside the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to join the highest ranks of the IEA. Its acceptance would formally recognize India’s role as an economic leader with tremendous potential as a buyer and seller of energy, a leading producer of renewable energy and a model for other countries with emerging economies.

“India kind of has an outsized role in the global energy dialogue right now, being an energy demand giant. IEA needs India to be at their table,” said Mohua Mukherjee, an independent senior energy expert working at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

For the last half-century, full membership in the IEA — an intergovernmental organization that promotes energy security and the world’s transition to clean energy — has been limited to the 31 members of the OECD. These are mostly high-income countries situated in the West.

India will first have to be accepted as an accession country — a designation given to countries on the way to full membership. Currently, Chile, Colombia, Israel, Latvia and Costa Rica are recognized as accession countries.

But India holds unique power as an emerging energy giant: it is poised to see the largest energy demand growth of any country because of its rapid progress toward industrialisation and urbanisation, combined with sharply rising per capita incomes.

“Having India as an advocate for the rights and the needs of energy consuming countries will be a good signal to have such a big player from the Global South as central to the energy conversations,” said Kaushik Deb, senior research scholar at the Center on Global Energy Policy, School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University.

India’s participation is necessary.

The IEA was established in 1974 during an energy crisis that arose when Arab countries stopped selling oil to the West. Its original purpose was to promote the energy security of OECD countries.

Over time, the IEA mandate expanded to include analyzing global energy trends, advising member governments on transitions to sustainable energy and fostering multinational cooperation. In 2016, the IEA broadened its concept again to add climate change into its vision of energy security.

Over the last decade, the IEA has sought to engage key non-members in its activities — particularly large economies important to the global energy transition. These countries were given a designation as associate countries and include Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, South Africa, Thailand, Singapore and Morocco.

Today, the IEA’s 31 member countries and 13 associate countries represent 75% of global energy demand.

In recent years, IEA has realized that India is an energy giant, Mukherjee said. Without India’s participation in efforts to reduce emissions, the pathway to limiting global warming to 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius would not be possible, she adds.

India — which now, with 1.4 billion residents, has surpassed China as the world’s largest country by population — is undergoing a period of growing energy demand, urbanization and industrial growth, making it a key player in efforts to hit global climate change targets.

Reforming India’s energy sector

India’s government, under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has made huge investments in the energy sector and brought in rigorous policy reforms to revamp its domestic energy structure.

The IEA reports that around 750 million people in India gained access to electricity between 2000 and 2019, including those living in isolated places. Having connected all households to the electricity grid, India is now targeting 24/7 supply.

Traditionally, India’s rural households have used biomass such as wood, animal waste and charcoal for cooking and heating purposes causing indoor pollution, especially affecting women and children. This is now being replaced with liquefied petroleum gas and use of solar energy for cooking, affecting 80 million mostly rural households, according to a report in Nature Energy.

At the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference, India pledged to reach net-zero emissions by 2070 and has achieved 50% of its 500-gigawatt renewable energy target ahead of time. Despite being the world’s third largest greenhouse gas emitter, India has one of the lowest per capita emissions. It’s also seen a 33% reduction in emission intensity of its GDP between 2005 and 2019.

India has been shifting its energy system towards renewables, electrification of its transport system and use of hydrogen and biofuels. In 2023, the country launched the National Green Hydrogen Mission, initiating a slew of measures for production, utilization and storage of green hydrogen. “India is probably going to have the world’s largest investment opportunities in all kinds of energy,” Mukherjee said.

A large share of India’s renewable energy growth is driven by solar photovoltaic installation, making India one the most attractive investment destinations for solar power according to Ernst & Young’s 2023 Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index (RECAI).

India is also introducing important energy pricing reforms in the coal, oil, gas and electricity sectors. For instance, the government wants to more than double the share of natural gas, from six to 15% by 2030, in the energy mix. It is one of very few countries where gas demand is rising, whilst most developed countries are winding down their gas demand.

A global model

India will serve as a model for low and middle-income countries as they develop economically while striving to meet climate goals.

“If India successfully meets its energy transition goals to fuel its economic growth, it would have established a new growth model where higher prosperity does not necessarily imply a much higher energy and carbon footprint,” Deb said. He added that this will have profound implications for the rest of the world that is yet to enter such a phase of economic growth.

Western countries have recently become more interested in investing in India as compared to China, where productivity growth has slowed and supply chains were disrupted during the pandemic, Deb said.

“It appears that countries in the West are seeing some sort of a technological threat from China. This is unlike the case of India which is apparently in a honeymoon phase in its relationship with the U.S. and the European Union,” Mukherjee said.

Will India join the Club as the first non-OECD country?

India’s green energy development pathway aligns well with IEA’s expanded energy security mandate and this synergy could be the basis of their partnership, Deb said. However, the road to full membership will be difficult as it will have to comply with phasing out of fossil fuels while continuing to grow simultaneously, he added.

“India will likely not be able to meet the IEA goals, particularly a 90-day stockpile of oil reserves. Even so, OECD countries may still give India a green light to full membership,” Mukherjee said.

India’s inclusive energy model

In India, more than 500 million people live on a daily wage and use two-wheelers or three-wheelers for transit. India is testing and applying business models for electrifying these vehicles in a cost effective way. Two-wheeler and three-wheelers are expected to drive India’s EV (electric vehicle) growth.

Daily needs products such as an electric-powered two-wheeler or even a solar-powered fans for very hot areas where grid power is unreliable and access to a cooling fan can be a life-or-death issue.

Solar-powered refrigerators for things like cooling essential vaccines or milk will be things required in the near future. These products are being developed in India because of its vast domestic market.

“The rest of the world’s low-income countries don’t have to go through the learning curve themselves. This is the huge benefit that India will have by sitting in the influential organization like the IEA once it has identified solutions at scale for making an inclusive energy transition,” Mukherjee said.

Three questions to consider:

- Is it important that non-OECD countries are members of the International Energy Agency?

- What will India’s role be in the IEA should it become a member?

- How can developing countries follow in India’s footsteps to support their economic growth while committing to global climate efforts?

Preety Sharma is a freelance journalist and an independent public health and development consultant currently based in Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India. She is a fellow in global journalism at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto.

Very well written article. India is undergoing silent green. revolution by harnessing solarn power, encouraging use of electric vehicles, green petrol by mixing ethanol..

It is a great article about green culture, I hope more countries join to this relevant idea world wide.