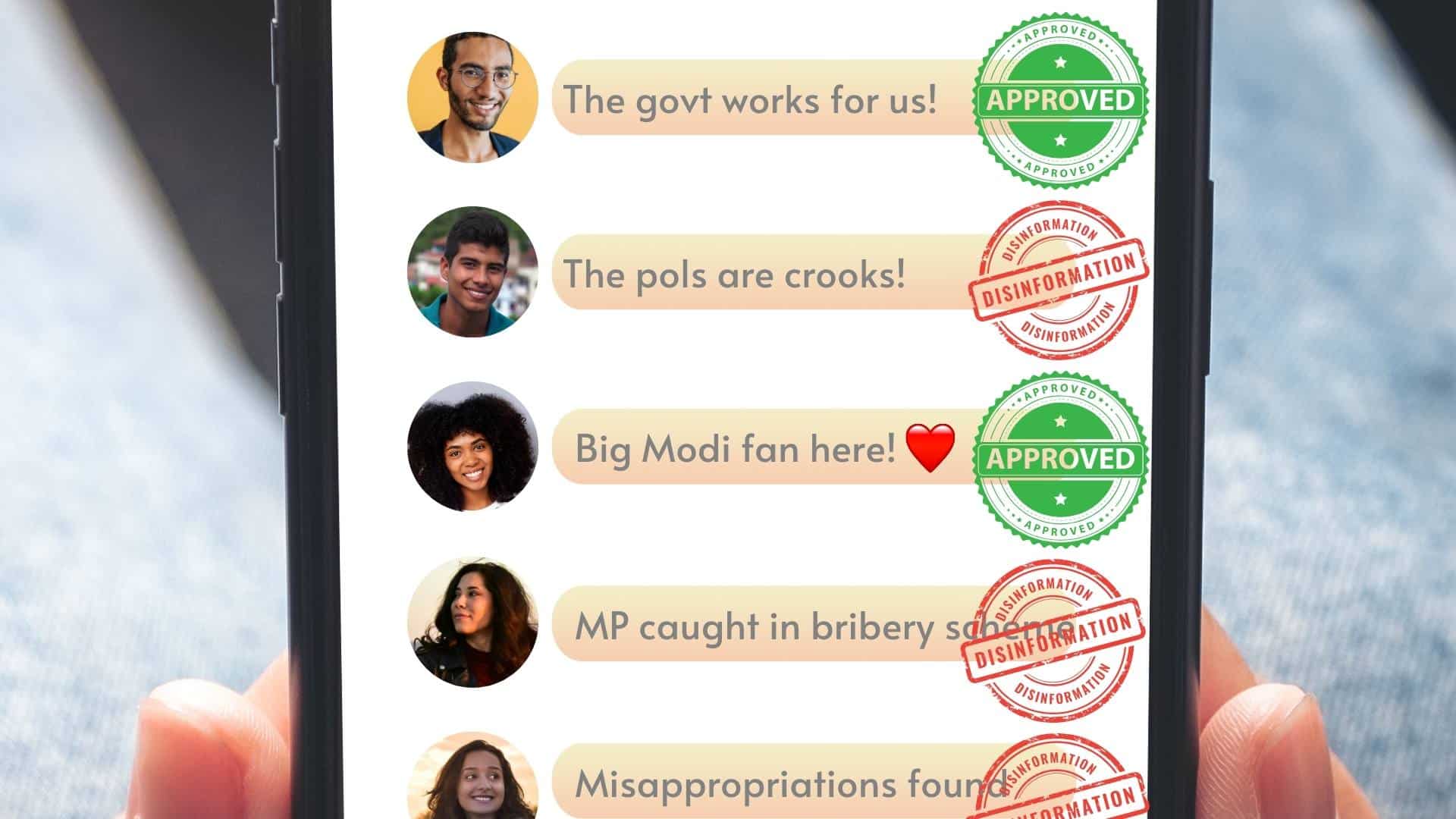

The Indian government seeks to establish a system to weed out disinformation. But it seems targeted at only posts that knock those in power.

Anti-government messages get stamped with a disinformation warning on a social media thread. (Illustration by News Decoder)

This article was produced exclusively for News Decoder’s global news service. It is through articles like this that News Decoder strives to provide context to complex global events and issues and teach global awareness through the lens of journalism. Learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program.

An Indian court has overturned the Modi government’s plan to setup a fact-check unit, finding it in breach of the freedoms of speech, business or profession and equality.

The verdict, which was announced on 20 September by the High Court of Bombay, the second-highest court in India, related to a series of petitions that contested a 2023 amendment to the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules.

It is a significant ruling.

The amendment empowered the Indian government to establish a fact-check unit to identify fake, false and misleading information about the government online. The unit would inform intermediaries — companies, such as social media and online gaming platforms, that facilitate interactions among internet users — about the flagged content. They would then be required to remove it.

“This is a big win for the freedom of speech and democracy in India,” says Gayatri Malhotra, litigation counsel at the Internet Freedom Foundation, a New Delhi-based nonprofit advocating for the digital rights and liberties of Indians, and one of the lawyers who represented the petitioners in the case. “Democracy is all about having everyone’s voice being heard and this judgment ensures that the government does not become the sole arbiter and gatekeeper of the marketplace of ideas.”

Some facts are more preferable than others.

The Modi government sought to reduce misinformation about itself with the 2023 amendment.

Pamposh Raina, head of the Deepfakes Analysis Unit, a division of the Misinformation Combat Alliance, a cross-industry collaboration to limit the spread of misinformation in India, said that misinformation is any form of content that is not accurate or where the facts are not 100%.

“When you share a piece of unverified information unintentionally, you become a purveyor of misinformation,” Raina said. “But when you share that piece of unverified information on purpose or you are somebody who is behind that piece of unverified information, you are spreading disinformation.”

The 2024 Global Risks Report, published by the World Economic Forum, identifies misinformation and disinformation as the most severe threats facing the world over the next two years. According to the report, India is particularly vulnerable to the information disorder.

“There are all kinds of misinformation with varying degrees of harm,” says Pratik Sinha, co-founder of Alt News, an Indian nonprofit fact-checking website. “There could be medical misinformation, for example, where someone says have X and it will cure Y.”

Fact-checking fairly

Alt News tries to address the political and societal kind of misinformation, which differs from country to country. In the United States, for example, misinformation targets Mexican immigrants, while in the Europe, Muslim immigrants are the victims.

“In India, the primary political story that plays out is the Hindu-Muslim issue, which is why there is a lot of misinformation around this,” Sinha said. “Any incident is given a Hindu-Muslim angle in an attempt to systematically villainize the Muslim community and show that they are the root of a lot of problems in India.”

There is also misinformation about government policies in India, he said. “For example, there are people who are running scams in the name of the government. This could be job scams, exam scams, hiring scams, all kinds of scams.”

Raina often considers the consequences of a piece of misinformation going viral. “Is it something that could impact your voting decision?” she said. “Is it something that could impact your health choices? Is it something that could lead to real-world harm such as sectarian conflagrations [conflict]? Could it, god forbid, kill people?”

Sinha said that misinformation is creating hate and division in our society. “People are then incapable of thinking of issues through an independent lens,” Sinha said. “So, misinformation and disinformation indirectly hinders the progress of a country.”

Turning platforms into propaganda

The Modi government sought to address one facet of all the misinformation swirling on the internet through its fact-check unit — fake, false or misleading content related to the government’s policies and operations.

This decision is set against the backdrop of a worldwide surge in government-sponsored fact-checking efforts, as seen in countries such as Brazil, Ethiopia and Indonesia. Aside from the Modi government, some Indian states, including Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, have also setup their own fact-check units.

However, critics worry that these initiatives serve as a platform for the government to spread its own propaganda.

“The government should not have any role in fact-checking simply because there is potential to misuse it,” says Karen Rebelo, an investigative reporter and fact checker with Boom, an Indian fact-checking website. “We’ve already seen instances where the government calls out some legitimate news as fake or false without explaining why. That is not how fact checks work.”

Sinha pointed to what happened when the government arranged for trains to carry migrant workers back to their hometowns during the Covid-19 lockdown.

“There were many people who died on those trains,” Sinha said. “The government in every such case, which was reported by the media, gave a blanket statement that they died because of previous illnesses. It had nothing to do with the train journey itself. But when we spoke to the families, they told us that the deceased did not have any previous illnesses and they died because of exhaustion, lack of food or water or whatever may be the case.”

The courts weigh in.

The court battle in India took a dramatic turn in January 2024 when a two-judge bench delivered a split decision on the legitimacy of the government’s fact-check unit. The case was then escalated to a third judge, who uncovered various flaws in the Modi government’s proposal. He sided with the petitioners that it could have a ‘chilling effect’ on India’s democratic values.

Malhotra said that when the person who decides what is fake, false and misleading is the central government, then the government becomes the judge, jury and executioner in its own cause.

“If the government flags something, the intermediaries will obviously take it down,” Malhotra said. “If they don’t, they would lose ‘safe harbour’, a provision in the law which protects them from being personally liable for third-party content posted on their websites. This could also lead them to enforce censorship overzealously.”

Sinha argues that the Modi government’s fact-check unit represented a narrow and short-sighted approach to addressing misinformation, since government misinformation isn’t the only kind of misinformation affecting people.

“But they brought about a policy change which said that if there is misinformation against the government, then the platforms need to bring it down,” Sinha said. “They have completely ignored all other kinds of misinformation, which is creating so much strife in our society. So, they are not interested in looking at misinformation as a holistic issue because it benefits them.”

Educating people to be media literate

Rebelo said that the government isn’t the only stakeholder in the information ecosystem. It also includes social media platforms, readers and consumers of news, fact checkers and journalists, “In this ecosystem, to give such sort of sweeping powers to the biggest stakeholder, who anyway has the largest platform for getting its message out, doesn’t make any sense,” Rebelo said.

Even as the Indian government is expected to appeal the decision of the Bombay High Court, experts suggest other measures that it can take to curb misinformation, such as investing in media literacy on how to identify fake news.

As an example, Raina said that the Deepfakes Analysis Unit shares short educational material on AI-generated misinformation and tips to debunk it, with people who share audio or video content on their WhatsApp tipline.

Individuals and communities should also take a moment to reflect on how they consume information, acknowledge the impact of information disorder on their lives and consider potential solutions to address it.

“A very simple rule of thumb is if a piece of information is too good to be true or it’s too bad to be true, it probably isn’t,” says Rebelo. “Even if it comes from a trusted acquaintance, it’s best to verify where the news is coming from.”

Three questions to consider:

- What is the difference between misinformation and disinformation?

- Should the government play the role of a fact-checker?

- How should we think about curbing misinformation and disinformation?

Shefali Malhotra is a health policy researcher based in New Delhi and a graduate of the fellowship in global journalism at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto.