It wasn’t too long ago that a woman wouldn’t dine alone in the United States. Two women decided to change that by opening their own restaurant.

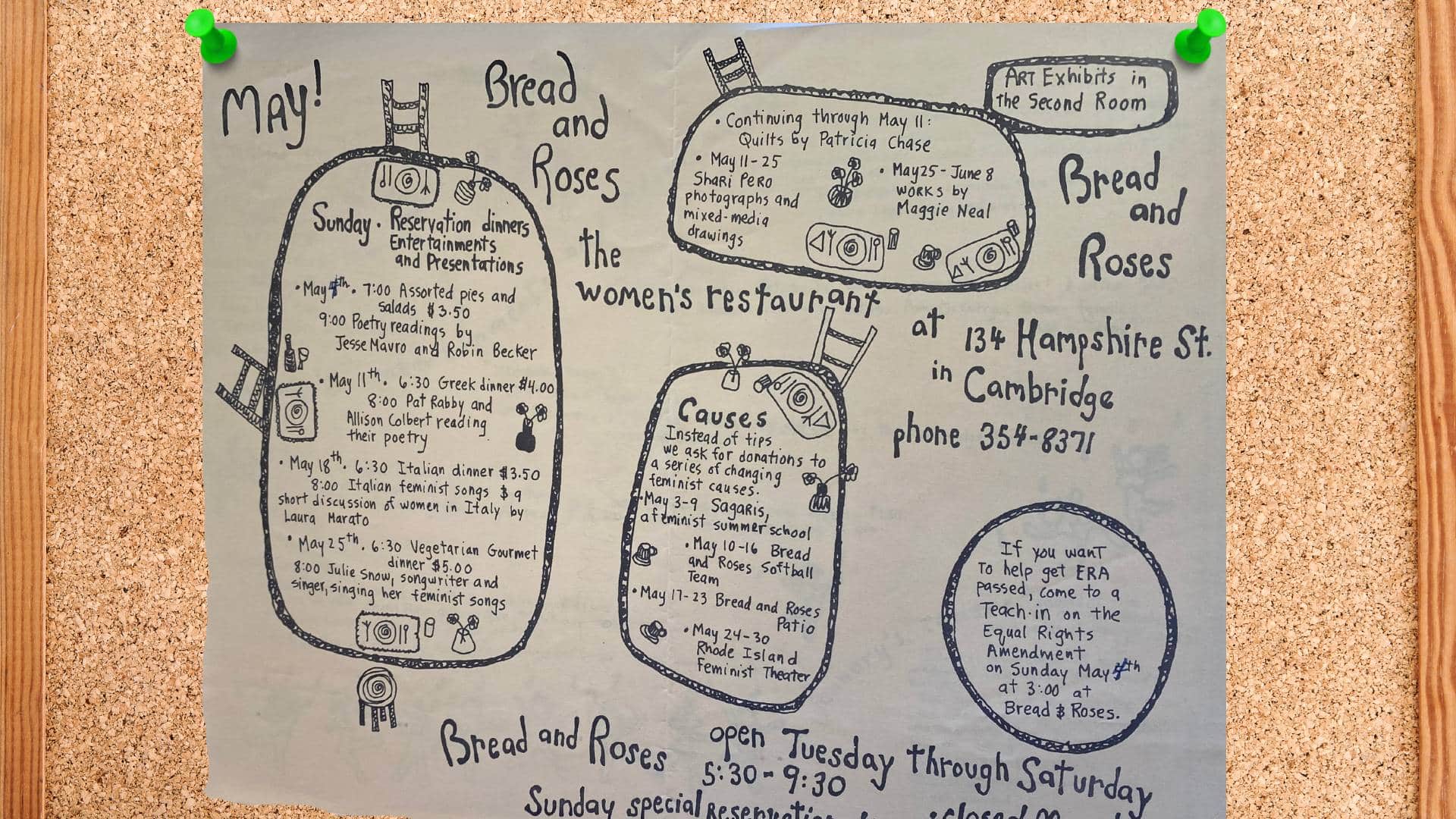

A notice once on the wall of Bread and Roses now housed at the The Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute at Harvard University. (Credit: Meera Raman)

A mass of women crowded onto the sidewalk of Inman Square one night in December 1974, eager to score a seat at a new restaurant that had just opened not far from Harvard University in the U.S. state of Massachusetts.

It was 50 years ago this month that Pat Hynes and Gill Gane opened the doors to Bread and Roses, intent on serving up food seasoned and soaked in feminist flavour. It was a revolutionary idea at the time.

The women that night bounded through the double doors, past the long countertops, handful of tables and walls adorned with feminist posters that defined the cozy vegetarian diner. Globe lights washed the room in a vibe that quickly created a hub that served up more than food.

“It was a place of refuge,” said Gilda Bruckman, who would co-found the feminist New Words Bookstore nearby, just a few months later.

Bread and Roses gave women a space to sit, read or just be without being bothered, said Alex Ketchum, a McGill University professor and author of “How to Start a Feminist Restaurant” and “Ingredients for Revolution: A History of American Feminist Restaurants, Cafes and Coffeehouses.”

“At the time, it was rare for women to dine alone,” Ketchum said. “They were often harassed or judged.”

The power of spaces

At Bread and Roses people could organize for women’s rights, watch performances or simply enjoy lunch in peace.

The restaurant lasted just four years, but in that short time it became a symbol of the feminist movement’s triumphs and tensions. It was part of what Ketchum calls a “feminist nexus” in Inman Square. A short walk down Hampshire Street led to other spaces for women including New Words, a feminist credit union and a women’s community health center.

Together, they made Inman a hub for organizing and tackling everyday challenges — like securing a loan without a man’s signature or accessing women-centered healthcare.

While those businesses are now gone, their influence endures. Inman Square remains a haven for women entrepreneurs, carrying forward the spirit of connection and feminist ideals. And Bread and Roses — named after the 1912 Lawrence textile strike — has become a blueprint for feminist businesses worldwide.

When Hynes and Gane opened Bread and Roses, they rented the space for $200 a month (around $1,200 today). Banks refused them loans, so they turned to the community, selling $100 shares to 100 women investors, with legal help from a women’s law collective down the street. Renovating the former bar was a collective effort, led by women architects and designers.

The transformation didn’t go unnoticed. Soon after the restaurant opened, someone penned a poem celebrating the change:

“They changed the gender of the place — that dirty old bar for men. They turned it right side up, you see – and made it feminine.”

This poem, along with other documents, now resides at Harvard’s Schlesinger Library, thanks to Hynes’ donation.

Empowerment spreads.

But Bread and Roses’ influence extended far beyond Cambridge. It drew visitors from across the world, including one woman who, co-founder Hynes recalls, traveled from Ireland just to dine there.

The restaurant also was a model for feminist businesses elsewhere, such as Bloodroot in Bridgeport in the U.S. state of Connecticut which continues to operate today, blending activism with community dining.

At Bread and Roses, the feminist mission was built into the business model. Profits were shared equally among workers, who earned double the minimum wage. Roles rotated — there were no permanent wait staff or dishwashers.

Instead of tips, customers could leave donations for a “social cause of the week,” raising $50 to $70 weekly.

But this egalitarian vision wasn’t without challenges.

Not all a bed of roses

In 1975, Hynes fired Claudia Leed, a worker accused of making customers uncomfortable, according to documents from the Schlesinger Library. Leed and two colleagues, Janet Stambolian and Jane Seligson, protested, publishing an open letter accusing Hynes of abusing authority.

The dispute sparked a larger debate: Should a feminist business be a collective or have leaders?

At a meeting at the Cambridge Women’s Center, over 60 women argued both sides. Hynes defended her decision, asserting that Bread and Roses was a partnership, not a collective. “We didn’t call ourselves owners,” Hynes said, reflecting on the restaurant in a 2024 interview. “But it was never presented as a collective, it was presented as egalitarian.”

Women, joined by men, picketed Bread and Roses calling Hynes “authoritarian” and “capitalist,” according to Hynes’ letters.

Mary Daly is a feminist philosopher and was a regular customer at Bread and Roses. She was one of 27 Boston-area women who signed a protest letter supporting Hynes. It argued that a woman should be able to show strength without being accused of authoritarianism.

A legacy of feminism

Ketchum said these tensions were common in feminist businesses.

Hynes said that after the protests the restaurant lost business and had to essentially start from scratch, Hynes said. But they had a successful next couple of years.

Four years after opening, Hynes sold the restaurant. It briefly reopened as Amaranth, another feminist eatery, before eventually becoming Daddy-O’s — a departure in name from its feminist roots. Today, the space is home to Oleana, a Middle Eastern restaurant led by celebrated chef Ana Sortun.

Despite Bread and Roses’ closure, Inman Square today reflects its legacy. Women-owned shops like crafting space Gather Here, the Albertine Press stationery store and the We Thieves clothing boutique continue the tradition of creating spaces for connection and creativity.

“There was this saying at the time, women together are women alone,” Hynes said. “This meant that if you weren’t with a man, you weren’t noticed, you were invisible. This restaurant countered that. It was a world where women could meet each other and socialize side-by-side in a space without fear for the first time in the area and that’s feminist history.”

Three questions to consider:

1. Why did the founders of Bread and Roses feel compelled to open a restaurant for women?

2. Why was it so difficult for women to gather together or eat by themselves in public in the United States 50 ears ago?

3. Can you think of places in the world where women still lack the freedom and power to gather together in public?

Meera Raman is a freelance reporter and personal finance writer based in Toronto. She is currently a fellow in the Dalla Lana Fellowship in Journalism and Health Impact at the University of Toronto.

There was quite a space of time between Bread and Roses and Daddy-0’s. After Bread and Roses, there was, from 1979 to 2001, the Modern Times Cafe, owned and operated by Howie and Wendy, a couple from New York and then by Ben Jeffries. This article entirely missed a significant twenty-two year span in the history of the space from Joe Silva’s Bar to Oleana Restaurant.