Contraception reduces mortality and can improve the lives of women. But the United States has pulled its global funding for maternal health programs.

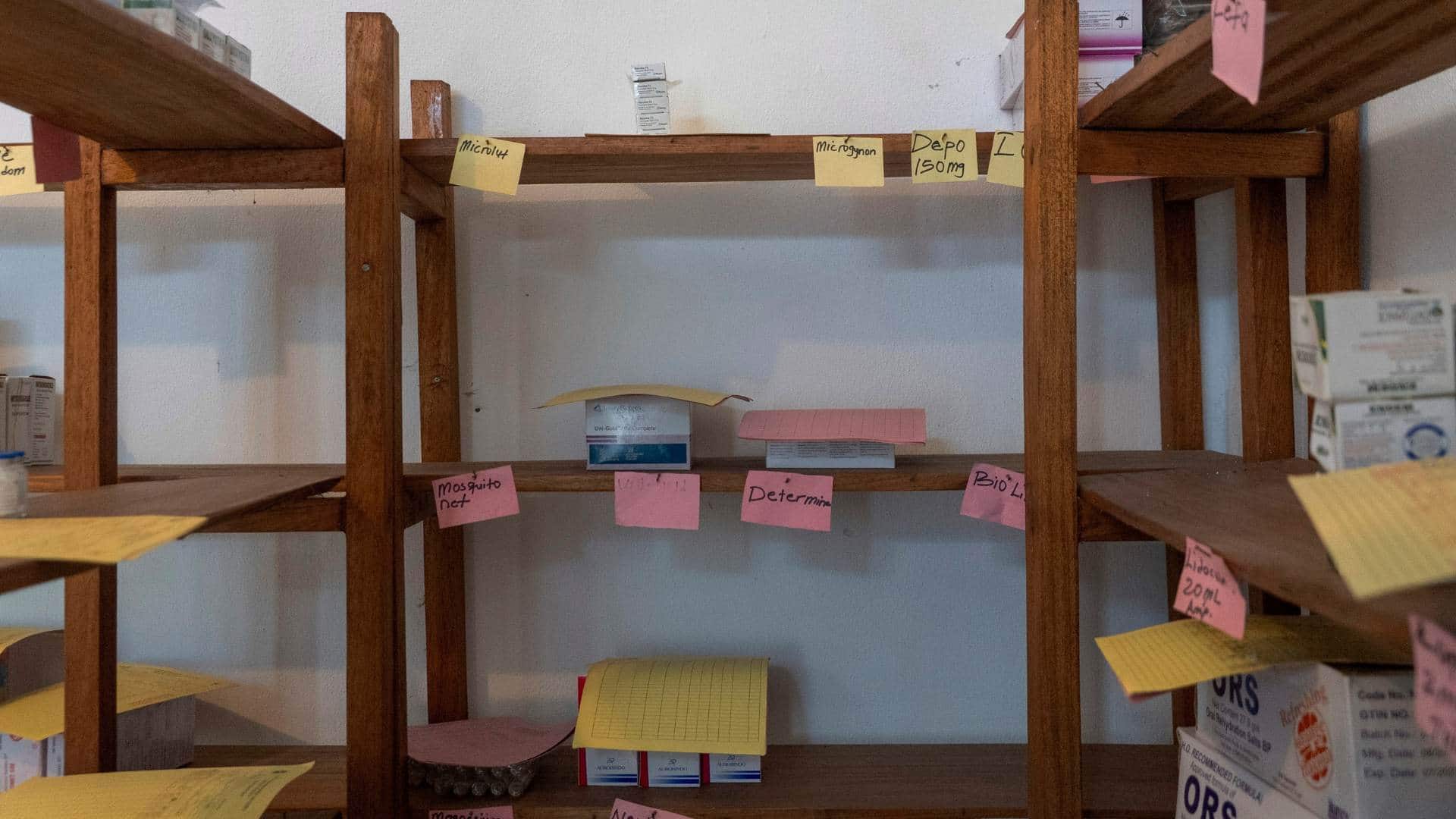

An almost-empty shelf, that once held contraceptives for patients, is seen at the Palala Clinic in Bong County, Liberia, 13 June 2025. (AP Photo/Annie Risemberg)

Abandonment of U.S. financial support for contraception around the world has disrupted the ecosystem that fostered birth control, family planning and sexual and reproductive health for decades.

Back in February, the United Nations Population Fund announced that the United States had canceled some $377 million in funding for maternal health programs around the world, which includes contraception programs.

Contraception reduces mortality and can improve the lives of women and families. The United Nations estimates that the number of women using a modern contraception method doubled from 1990 to 2021, which coincided with a 34% reduction in maternal mortality over the same period.

Now, tens of millions of people could lose access to modern contraceptives in the next year, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a family planning research and lobby group. This, it reported, could result in more than 17 million unintended pregnancies and 34,000 preventable pregnancy-related deaths.

Sexual and reproductive health and rights programs improve women’s choices and protection including violence and rape prevention and treatment.

Who will fill the gap?

European donor governments have pledged to increase contributions to UNFPA and other global health funds to partially fill the gap. The Netherlands, Sweden and Denmark, for example, have pledged emergency funds to UNFPA Supplies, the world’s largest provider of contraceptives to low-income countries.

The EU has also redirected part of its humanitarian budget to cover contraceptive procurement in sub-Saharan Africa. Canada announced an additional CAD $100 million over three years for sexual and reproductive health programs, explicitly citing the U.S. withdrawal.

Despite its own aid budget pressures, the UK has committed to maintaining its £200 million annual contribution to family planning programs, with a focus on East Africa.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation expanded its Family Planning 2030 commitments, pledging tens of millions in stopgap funding to keep supply chains moving. The World Bank Global Financing Facility offers bridge loans and grants to governments facing sudden gaps in reproductive health budgets and calls for governments to co-finance. However these initiatives will not immediately replace the scale of previous U.S. government investments.

The loss of U.S. support has left many women with no access to family planning, especially in rural and conflict-affected areas. Clinics are reporting a surge in unintended pregnancies and unsafe abortions.

Health clinics closing

In Zambia, Cooper Rose Zambia, a local NGO reported laying off 60% of its staff after receiving a stop-work order from USAID. Clinics have been rationing contraceptives with some methods already out of stock.

In Kenya, clinics in Nairobi and rural counties are turning women away, with some supplies stuck in warehouses and at risk of expiring. In Tanzania, medical stores confirmed they were completely out of stock of certain contraceptive implants by July 2025.

Mali will be denied 1.2 million oral contraceptives and 95,800 implants, nearly a quarter of its annual need. In Burkina Faso, another country under terrorist insurgency internally, many displaced women have no access to modern contraceptives.

The consequences of the stock depletions will be particularly catastrophic in fragile and conflict settings such as refugee camps.

Struggling to adapt to the reality has led organizations to cut programs and redirect their remaining resources. Many are trying desperately to raise new funds. But there are some voices that cheer the cuts, describing them as a wake up call.

A wake up call for Africa?

Rama Yade, director of the Africa Center of the Atlantic Council, a non-partisan organization that studies and facilitates U.S. international relations, argues that the aid cuts could be a wake-up call for African nations to reduce dependency and pursue economic sovereignty.

For pan-African voices who have long criticized foreign aid as a tool of neocolonialism, the U.S. government cuts are a chance to build local capacity, strengthen intra-African trade and reduce reliance on Western donors. Trump’s dismantling of USAID offers a new beginning for Africa.

In an essay in the publication New Humanitarian, Themrit Khan, an independent researcher in the aid sectors wrote that recipient nations have been made to believe they are unable to function without external support.

Khan proposes several actions to mitigate the foreign funding cuts: relying more on local donors; developing trade and bilateral relations instead of depending on international cooperation programs through the United Nations and other international organizations; re-evaluating military spending and reducing debt.

Colette Hilaire Ouedraogo, a senior midwife and sexual and reproductive health practitioner, told me that up to 60% of activities were from external funding partners. She recalled the alerts sent by the health department to increase funding from national sources as early as 2022.

She predicts that the cuts affecting the availability and access to contraceptives and the overall quality of services will slow down progress towards universal health coverage targets and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. There is a risk of reduced attendance at reproductive health and family planning centers. Consequently, unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions could increase leading an higher maternal mortality.

Questions to consider:

1. How can contraceptives result in lower deaths for women?

2. Why do some people argue that the cut off of funds from the United States might ultimately benefit nations in Africa?

3. Why are contraceptives controversial?

Georges Ki-Zerbo is a fellow in journalism and health impact at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health. He is the former head of the World Health Organization missions to Iraq, former Director of the WHO Office to the African Union and UN Economic Commission for Africa. He also headed WHO’s missions to Guinea, Chad and Equatorial Guinea and served as its Coordinator for Central Africa and leader of the Communicable diseases area of work.