Across the globe, tourist hubs are losing their love for the visitors who throng to them. Can an equilibrium be reached?

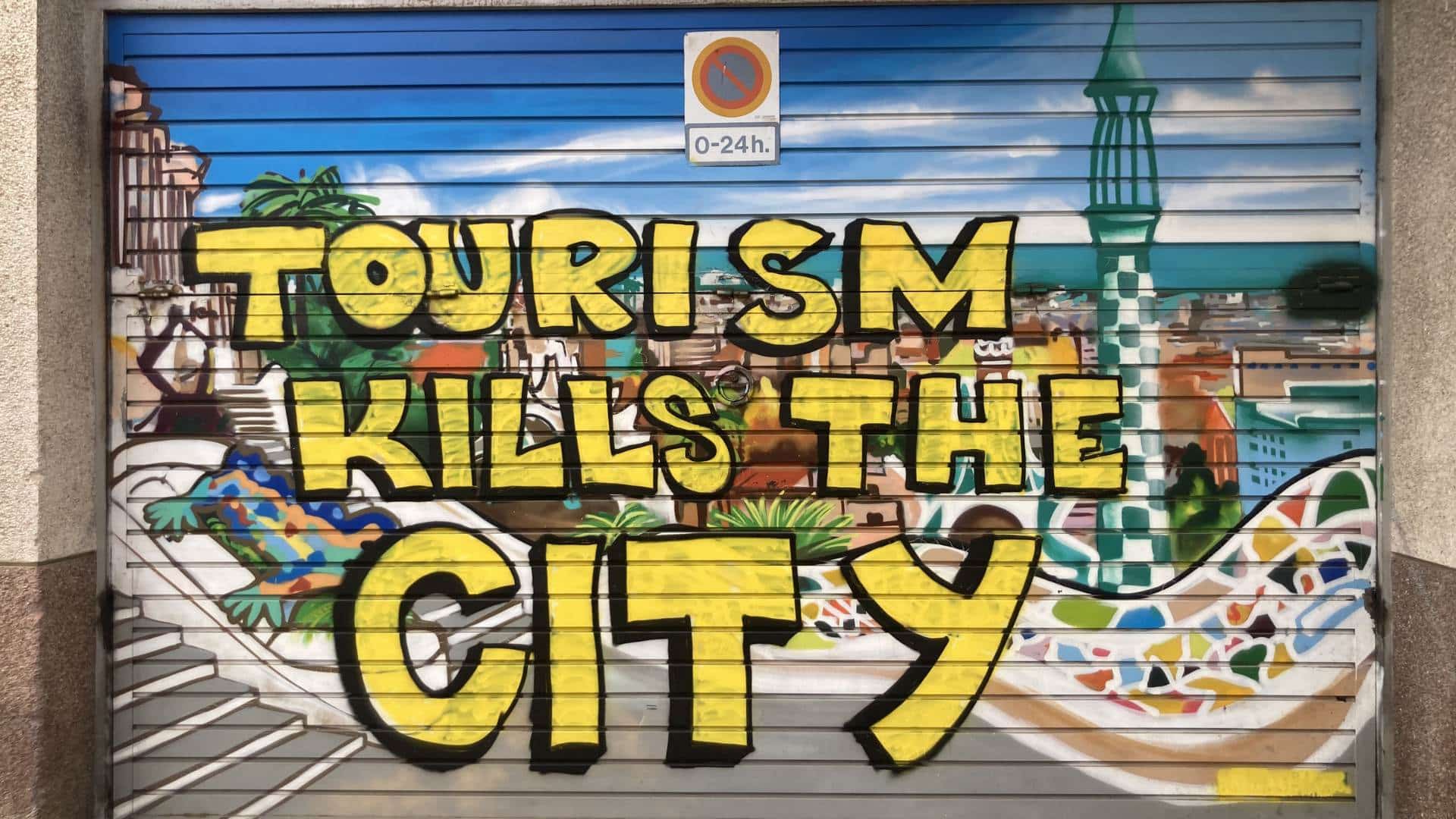

Graffiti on a garage reads “Tourism Kills the City”. (Credit: Leah Pattem)

This article was produced exclusively for News Decoder’s global news service. It is through articles like this that News Decoder strives to provide context to complex global events and issues and teach global awareness through the lens of journalism. Learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program.

I’m not a tourist in Madrid, but sometimes, I probably look like one. When I’m out for a drink with my partner, we speak English to each other — he’s also from the UK — but the way we approach the bar is our best attempt at blending in.

Being a local in Madrid is knowing how to navigate a packed taberna and still find a space up at the bar. It’s building a rapport with the waiter and being patient. They’ll get to you soon.

Then, when they finally ask you what you want, it’s knowing that there are usually only two white wine options — Rueda and Albariño -– ordering quickly with solid eye-contact and confidence, and then picking up your drink with a ‘gracia’, dropping the ‘s’.

These small details have taken me years to define and perfect. They’re subtle, but they signal something important: even if I’m speaking English, I live here and I am not a tourist. And that matters to me more than ever because, lately, being mistaken for a tourist in Spain has started to feel very uncomfortable.

Across Spain, Italy and Portugal, anti-tourism protests against the reshaping of cities to serve tourists rather than residents are growing louder and evermore coordinated. In 2024 alone, nearly 100 million tourists visited Spain, and even more are expected in 2025.

When tourists aren’t welcome

In response, graffiti reading ‘Tourists go home’ has become normalised — but even ‘Kill tourists’ has appeared in parts of the Canary Islands. In Barcelona, some residents have squirted tourists with water pistols in symbolic protest, although some seem to be actually attacking tourists with water.

In my own neighbourhood of Lavapiés in Madrid, ‘Fuck Airbnb’ stickers and graffiti now mark the windows of many short-term rental flats. But while such reactions don’t represent everyone, they reflect a rising frustration: the feeling that locals are helpless to being priced out of their own communities.

Mass tourism is undoubtedly linked to the rise of housing costs, strains on local infrastructure and insecure, low-wage employment — all while the financial benefits flow largely to property owners and platforms like Airbnb, many of which don’t pay their taxes here, if at all.

Local concerns are valid, but the issue of overtourism raises a deeper question: are tourists the problem, or are they simply the most visible symptom of something much more powerful?

Governments across Europe are experimenting with ways to address overtourism. In Spain, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez has promised extensive house-building, and the Ministry of Consumer Affairs has moved to fine Airbnb for advertising unlicensed apartments. But the regional responses vary widely.

Governments respond.

Barcelona has taken a firm stance, pledging to eliminate all tourist rentals by 2028, including licensed short-term rentals. Meanwhile in Madrid, the city council has swung the other way, opting to rezone entire residential buildings for tourist use. If this plan goes ahead, an estimated 6,000 residential buildings — plus thousands of ground-floor commercial units — could be turned into short-term holiday rentals, displacing both residents and shopkeepers.

At the same time, the capital’s housing crisis is deepening. Over the past decade, Madrid’s population has increased by 750,000, driven mostly by migration. In the same period, rents have increased by 80%, surpassing growth in wages.

Even beyond Madrid, the Bank of Spain found that nearly half of tenants in the country spend 40% of their income on rent and utilities, and also calculates a deficit of around 500,000 new homes. The director general of economics, Ángel Gavilán, estimates the need for building 1.5 million social housing units in the next 10 years to avoid deepening the current housing crisis.

While the Spanish government generally recognises the economic contribution of global immigration, housing construction in Madrid is failing to keep pace. Rents for businesses have also soared due to reduced supply as empty units are replaced with short-term rentals. The result is a chaotic, profit-driven housing policy that threatens to reshape Madrid’s identity — including the no-frills bars where the wine list still has only two perfectly sufficient options.

Overcoming overtourism

Other parts of the world are also grappling with the challenges of overtourism and exploring new ways to manage it. In Japan, last year, a flood of tourists descended on the resort town of Fujikawaguchiko to photograph the iconic Mount Fuji, disrupting daily life to such an extent that residents banded together to build a wall blocking the view.

In response, Japan has introduced an entry fee for those wishing to climb Mount Fuji, though controlling access to the mountain’s view remains difficult.

To protect its cultural heritage sites, Japan is also set to introduce a dual-pricing system where foreign visitors will pay higher entrance fees than locals — a model already in place at landmarks in India, like the Taj Mahal in Delhi, or the Charminar Mosque in Hyderabad.

But instead of simply blaming tourists or increasing their costs, we should take a closer look at how tourism profits are collected and distributed. While entrance fees and tariffs are often justified as necessary for preserving cultural heritage sites, the revenue they generate should also benefit the broader community — supporting local housing, public transportation and essential infrastructure.

A more equitable approach would ensure that tourism contributes to the well-being of both visitors and residents alike. The ultimate solution lies in building — not just more homes, but also affordable hotels, rail lines and services that can absorb the pressure of increasing population and tourism. We need to decentralise both where people live and where tourists go.

Making a popular city affordable

Right now, the centre of Madrid may offer more bars and wine choices than ever before, but it comes at the cost of affordable drinks and, worse still, an affordable place to live.

None of this is the fault of the tourist. Spain has spent decades developing its tourism industry, which now accounts for roughly 15% of national Gross Domestic Product, or GDP, which is the total value of goods and services produced and is often used as a measure of the health of a national economy.

Millions of Spaniards depend on tourism for their livelihoods, and they want the sector to thrive. But that shouldn’t come at the expense of local resources or the right to housing.

If Spain, and other countries currently suffering the effects of too many tourists, is to remain welcoming to tourists, residents and immigrants alike, it must invest tourism profits back into the communities bearing its weight by designing and building a country for everyone.

Gracia.

Questions to consider:

1. Why are residents of Madrid and Barcelona angry at tourists?

2. What are countries like Spain and Japan doing in response to anger over tourism?

3. Have you been a tourist anywhere? How do you think you were viewed by the residents who live there?

Leah Pattem is a British Indian multi-award-winning freelance journalist, photographer and broadcaster covering Spain’s migration crisis, housing crisis and community stories. In 2016, Leah founded Madrid No Frills, a citizen journalism project focusing on the city’s social issues and movements. Leah is a trained teacher and runs storytelling courses for all ages, levels and backgrounds. She also hosts regular free in-person events to get audiences engaged in her biggest stories.