People might read about a problem but they’ll soon move on if the story doesn’t convince them something needs to be done. They need proof.

In News Decoder’s Top Tips, we share advice for young people from experts in journalism, media literacy and education. In this week’s Top Tip, News Decoder Educational News Director Marcy Burstiner explains how to find and use documents in a story to make it more convincing. You can find more of our learning resources here. And learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program or by forming a News Decoder Club in your school.

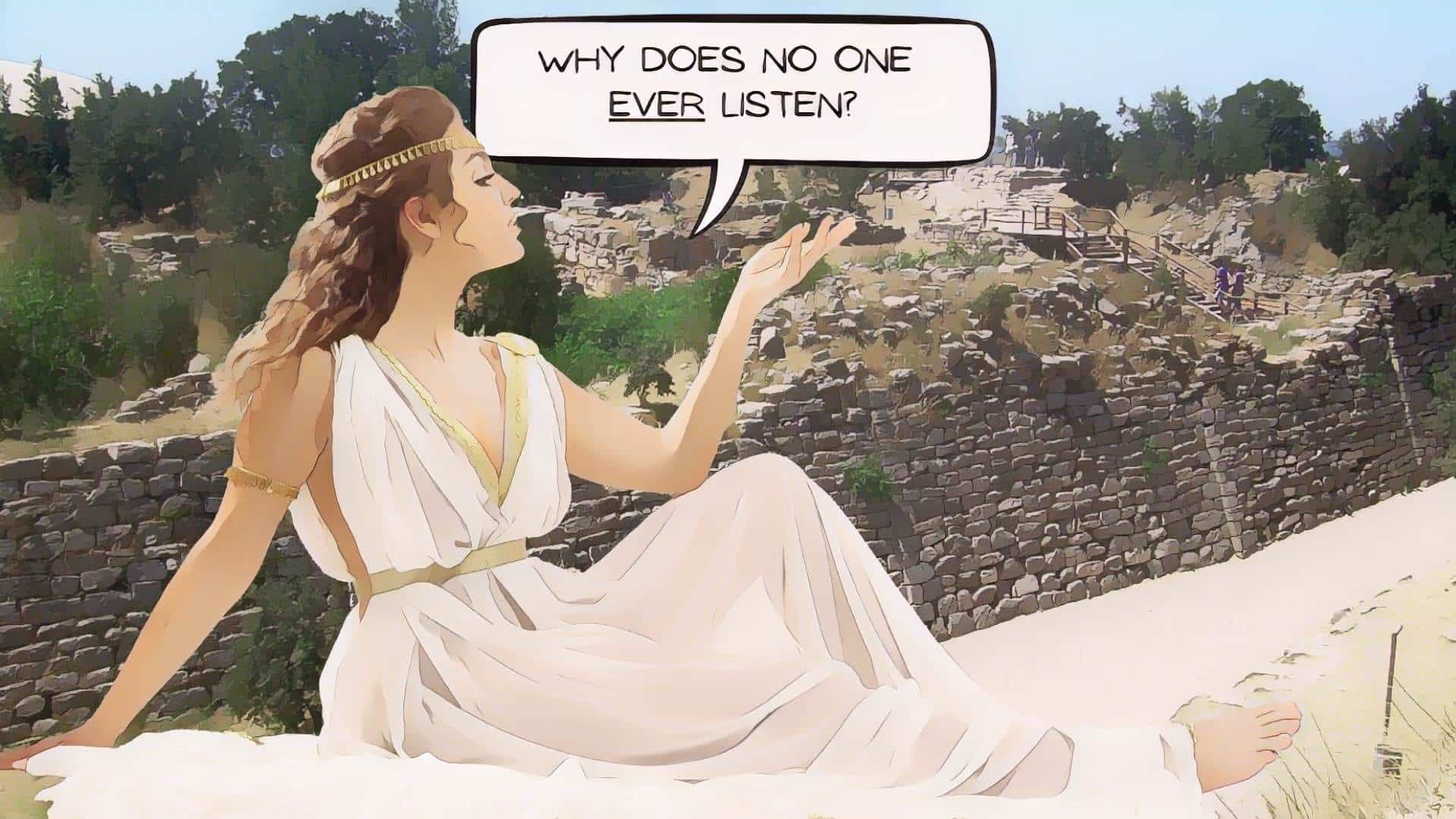

In Greek myths, Cassandra of Troy had this curse from the gods: She was able to see disasters before they occurred but no one would believe her warnings. Journalists can empathize. Often stories inform people about dangers but it seems no one listens.

That’s why a story needs to not just inform but to convince. And to do that you need more than quotes from reputable people. You need documents. In journalism, documents serve as a type of proof, like fingerprints or DNA in police dramas.

Documents can take time to get, but if you can include that type of proof in a story, the article is much more convincing. And there are all kinds of documents you can find. Think about how many times you are asked to fill out a form. We fill out forms when we get hired, buy a car, lease a flat, get a license, apply for a visa or get utilities.

On top of that, the offices you interact with fill out forms, from your doctor and teacher to your electrician and mechanic. That’s because they have to abide by all kinds of laws. That means that all kinds of governments — city, state, county, province, national — collect all kinds of data.

All kinds of people write reports for myriad committees and agencies. And all these reports and forms and data get duplicated and distributed and stored.

Much of it is available for the asking and in this digital world we live in, it is searchable and downloadable.

The search for proof

There is so much information out there that a search for them can be a time suck. So before you start your search ask yourself the following questions: What do I want to know and what kind of documents might hold the answer?

Once you identify what you need, figure out where it might be. Is it information filed with the government? Is it an internal corporate report? Is it something written by a committee of some kind? Who might have written the report or letter or gathered the data?

After you brainstorm where it could be, you can figure out how to get it. In some 70 countries, laws exist that give people the ability to access some government information. In the United States this is called the Freedom of Information Act and in its various states the laws are known as public records acts.

Where those laws exist, you can request the information if you can figure out who has is.

Where you don’t have the right to it, you can still request it from the people who have it, beginning with whoever wrote it. If it is a committee report, there are multiple people on that committee who received it. Then there are all the interested parties to whom they might have sent it.

Using advanced Google

But sometimes you aren’t sure what you data you need or what might be out there. Sometimes it helps to stumble around a little. That’s where Google Advanced Search comes in. You can find it by googling Google Advanced Search or by entering a search term into the main search and then hitting the “Tools” tab.

It allows you to search by country, by domain (.gov or .edu for example) and by file type. That means that you can search for PDFs or data in Microsoft Excel or Powerpoint presentations.

Separately, you can search for information created and shared in Google Slides, Sheets or Documents by adding the following terms to a Google search: site:docs.google.com, site:docs.google.com/spreadsheets, and site:docs.google.com/presentation.

The trick is to combine the region with the name of a type of place you think might have the information with the type of document it might be in. For instance, if I put in the terms “environment” and “committee” in the search bar for my subject and add “audit” for the type of document and then specify “region: Australia” I stumble on an uncorrected 2024 report from the Environment and Communications Legislation Committee of the Australian Senate.

But what do you do with documents and data once you have it?

What a document or data can show

• It might identify a possible problem. There might be a warning in a report that a bridge or dam or building or river is unsafe or that maintenance is underfunded.

• It could show actuality. That means that it could confirm that something you only know about by rumor or tip actually occurred.

• It might point to the person or organization responsible

• It could establish what should have happened. Governments and organizations set baselines, standards, guidelines and best practices. If you compare those to the events that took place you can see what went wrong and why.

• It could uncover a pattern. Generally one occurrence of something isn’t a big story unless it was something really bad that happened. But if you can find many people who had the same problem or many occurrences of it, it is a story worth reporting.

• It could quantify a problem. A doubtful person might demand: But how many times exactly did this happen? A report or spreadsheet might give you that answer.

Ultimately, documents and data can help you connect dots — a collapse of a building to under funding of maintenance and pressure on building supervisors to ignore inspection reports.

Now, documents and data alone are not enough. That’s because they tend to be a dry read. They need to be combined with the emotion and passion you get from human sources who care about what happened and what should be done.

Testimony from real people and context by real experts combined with documents and data. That’s what makes for a convincing and compelling story.

Three questions to consider:

- Why do you need documents or data to make a story convincing?

- What is one thing a document can provide?

- What are some forms you have had to fill out over the course of your life?

Marcy Burstiner is the educational news director for News Decoder. She is a graduate of the Columbia Journalism School and professor emeritus of journalism and mass communication at the California Polytechnic University, Humboldt in California. She is the author of the book "Investigative Reporting: From premise to publication."