It is one thing for students to read what a teacher assigned. It’s another to discover information themselves and use it to inform others and take action.

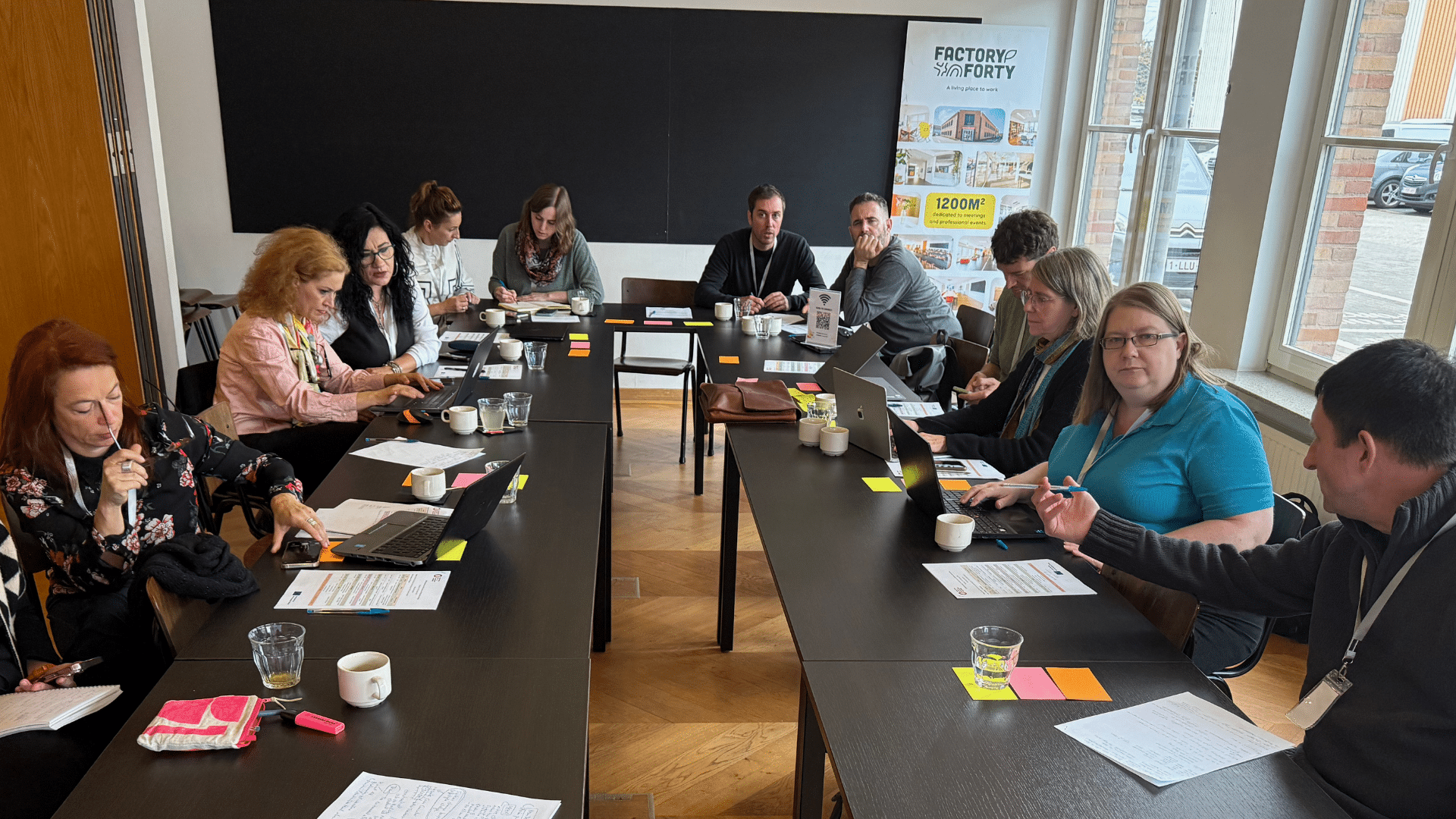

Educators work together in an EYES teacher training workshop in Brussels, Belgium, October 2025. (Photo by News Decoder)

A good teacher stays with you. For me it was my Grade 9 English teacher, Mrs. Renshaw, who was an eagle in a smart skirt suit, her beak always pointed in your direction, her eyes sharp and seeing. She scared us.

The highest value, she often said, was “self discipline”. You would not be late to Mrs. Renshaw’s class.

She stays with me not because some students cried under her screech, but because of the way she taught. We would begin every class by writing a caption to a funny image — a bicycle with square wheels or a whale breathing on land.

We would then read, all together, one student out loud at a time, before discussing the themes of the story and its meaning.

We didn’t have to wait for social science or psychology class to discuss such things as war, power structures, human instinct or violence because in Mrs. Renshaw’s class, we read and discussed “Lord of the Flies”. She thrived on hearing our interpretations of an author’s intentional and unintentional meaning and on hearing the stories we would come up with ourselves.

She passed away a few years after I left high school, but Mrs. Renshaw left something powerful with me: A passion for stories as a way of understanding our world.

Learning through stories

For all teachers out there, Mrs. Renshaw left this lesson: Stories could be the main vessel through which we teach and through which we can empower youth.

This is the heart of the EYES project.

It started as an idea, almost precisely two years ago, driven by the bright headlights of two organisations: News Decoder and the The Environment and Human Rights Academy.

The goal? Combine authoritative climate education and journalism to create a pathway for youth to deep knowledge.

We would design a climate change curriculum with a systems approach and justice lens, grounded in storytelling, to provide teachers with an innovative and flexible way of teaching something multifaceted and vital — and to provide students with the agency to take action.

The curriculum wouldn’t prescribe shorter showers or fewer beef burgers. It would instead shine light on the systems that keep the climate crisis in a relentless spiral and the injustices that have come as a result. And it would give students this fundamental task: Find the stories of the people and systems at the heart of climate change, but in their own communities and circumstances. We would guide them in communicating these stories to the world.

Seeing the small parts that make a big problem

They could start, maybe, with saving water if they have water to save and eating a plant-based diet if that’s available and affordable to them, but they should understand those are just pieces of a giant problem.

By finding and telling stories, by being a journalist in one’s own community, students can start to connect the different pieces of climate change to their own circumstances and to feel a different sense of agency.

Producing the climate storytelling curriculum was one thing. The challenge was getting it into schools. We ended up piloting it in ten countries — five in the European Union, five outside Europe — to gather feedback and refine the materials into a curriculum that can be added to any educator’s repertoire.

We soon collided with reality. Tight school curricula leave little room for innovation. Teachers are busy. How to present something both complex and innovative in a way that is engaging, tangible and accessible to all students between the ages of 15 and 18?

We built up a team of pilot teachers — springboarding from our networks -– and gave them a set of seven modules that explored such things as fossil fuel emissions, the carbon budget, climate justice and reasons to focus away from individual carbon footprints.

Reporting climate change

The modules included a project for students. They would pick a topic and report on it as journalists. That meant conducting interviews, gathering data and presenting it in a multimedia format.

We imagined deep investigations, groundbreaking documentaries, enlivened youth.

We organised in-person events to see how this curriculum would empower students in real time. In Brussels, we spoke with students about how emitting fossil fuels stays profitable and about how one area in Mumbai can be six degrees hotter than its immediate — and wealthier -– neighbouring area.

In Paris, students pitched stories about climate injustice, and in Pristina, Kosovo, Roma students drew images of their own lived reality of climate change. We were in Romania and Serbia, and in two alternative education spaces in Portugal, where all modules were delivered to students who came from complex social backgrounds.

We supported our pilot teachers in Cameroon, Colombia and Kenya from afar and connected students in Colombia, Kenya and Slovenia by making them “pen pals” so they could exchange letters on their differing lived experiences of climate change.

Change doesn’t come easy.

But we kept falling back onto the same challenges: time is squeezed at schools and climate injustice — a reality often experienced “elsewhere” — is hard to convey to young people.

We get it. The economic system that climate change is rooted in is a hard one to grasp when you’re trying to figure out whether to go to university or how to get a job or what career to train for.

It was disheartening. Was anyone really being empowered? There was little pick up and a whole lot of resistance, despite the innovative social science research that was at the heart of our program.

And so again, we came back to the thread of the project — storytelling. After all, as author and organizational consultant Peg Neuhauser said: “No tribal chief or elder has ever handed out statistical reports, charts, graphs or lists to explain where the group is headed or what it must do.”

It was in a conference room just south of Brussels, over three days in crisp October, that the wick of the project’s candle was finally lit. Educators from across Europe gathered around a large table to revitalise their teaching and, as the project was coming to a close, they opened a door I’d turned a blind eye to.

Inspiring teachers to empower youth

They listened, they contributed and they gave us a sense that we’d done it. We had laid down the soil. We had planted the seeds. All we needed were enthusiastic and present teachers to find the time and space to be together. This was the bright and warm spring we were waiting for.

We saw that our curriculum was not a rigid product but a set of concepts, pedagogies and ideas that could be adapted by skilled and passionate teachers. And we could trust them to do that. The magic wasn’t in what we gave them, but in feeding the fire they already had for teaching climate change.

The EYES curriculum is now as follows: 16 standalone classroom units each dealing with one concept — from tipping points to systemic change, from human–nature connection to green extractivism — and each including a bite-size storytelling activity such as come up with a pitch, explain a concept, make a connection. It includes six journalism guides from the principles of journalism and how to spot greenwashing, to how to interview and write an article.

There’s an Educators’ Guide produced from the brainstorming of that workshop in Brussels, a blog written by educators and students and a podcast series featuring brilliant thinkers. All materials are freely available to educators wherever they teach.

Ultimately, the success of EYES comes down to people: The educators; the advisory board; the students who were enlightened and empowered; the brilliance, strength and kindness of Andreea Pletea at The Environment and Human Rights Academy and her intimidatingly intelligent colleagues Anka Stankovic and Sebastien Kaye; the team at Young Educators European Association who bolstered the project when it was needed by helping to reach more students; Matthew and Jules Pye of The Climate Academy for transforming my way of seeing this global challenge; and my fantastic, curious and creative colleagues at News Decoder.

Empowering Youth through Environmental Storytelling comes to an end on 31 December. And as I close my laptop on EYES for the final time, I am assured that I leave behind something that will continue to spread in classrooms and help teachers and students find the climate stories yet to be told.

As Mrs. Renshaw taught me: A story does not end on the last page. It lives on in those it touches.

Questions to consider:

1. How can storytelling help students learn?

2. What does it mean to look at a problem at the systems level?

3. If you were going to explore a topic related to climate change, what would you tackle?

Amina McCauley is News Decoder’s climate education program manager. Born in Australia and living in Denmark, Amina has a background in reporting, media analysis and teaching and a particular interest in the relationship between humans, their environment and the media.