In Tasmania, students are learning how to prepare for a warmer planet and ways they can realistically help slow down climate change.

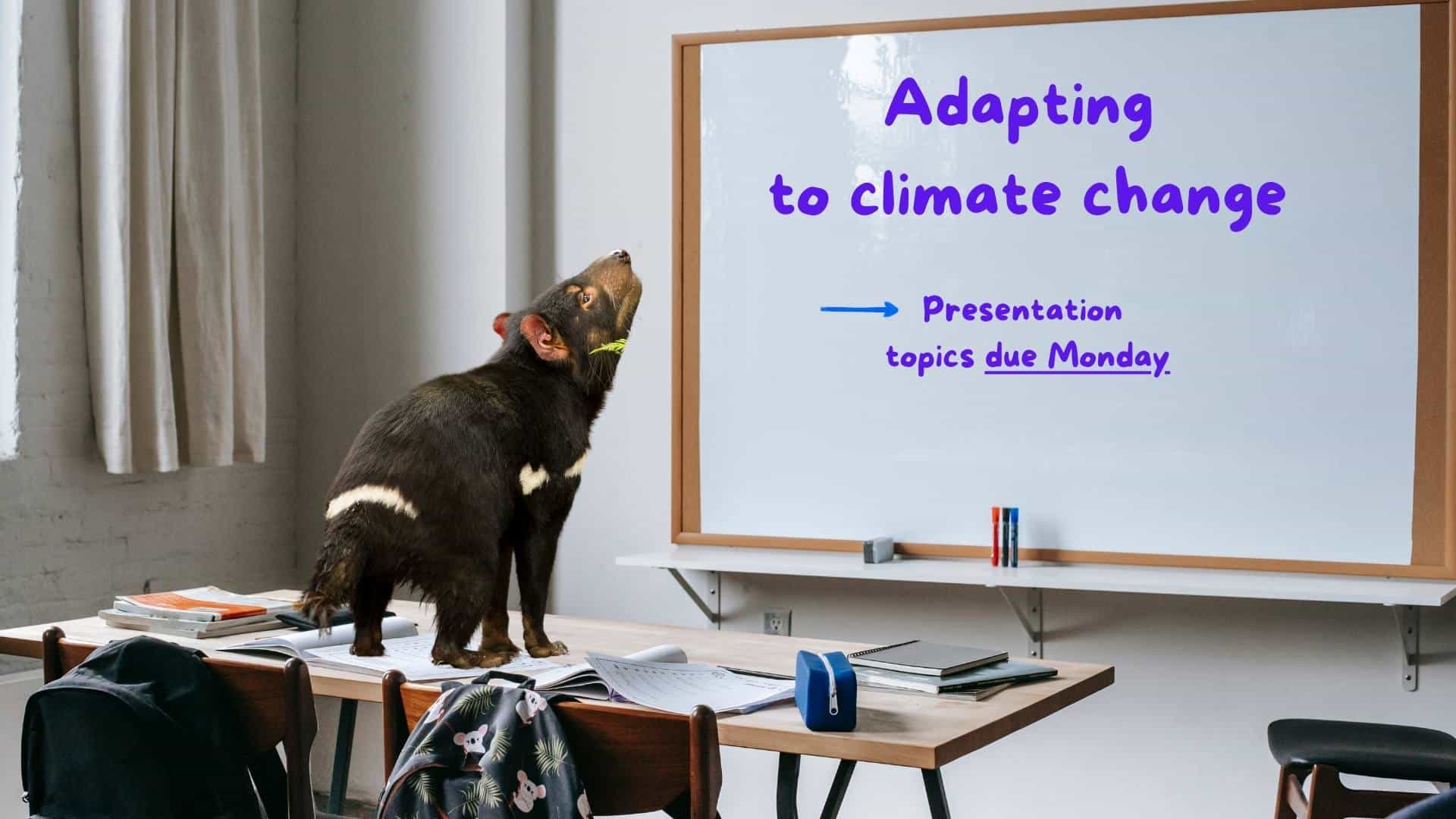

A Tasmanian devil in a classroom. (Illustration by News Decoder)

This article was adapted from the second episode of EYES on Climate, a podcast created as part of Empowering Youth through Environmental Storytelling (EYES), a News Decoder project in partnership with The Climate Academy in Brussels. In this episode, host Amina McCauley reported from Tasmania, where the environment is inherently connected to the sociopolitical fabric of the Australian state.

You can find the full episode embedded in this article below. EYES is halfway through a two-year project to create a series of classroom modules that educators across the globe can use to teach students to understand and communicate climate change through science and journalism.

News Decoder is piloting this curriculum in schools across the world — from Belgium and the Netherlands to Malaysia and Colombia. EYES is co-funded by The European Union. Let us know if you would like to become a pilot school or if you would like to know more about News Decoder’s global citizenship and media literacy programs for high schools.

In 2000, Chloe Lucas arrived in Australia on a working holiday visa.

“I was already a diver, and I really wanted to dive on the Great Barrier Reef,” she said. “I really fell in love with the Great Barrier Reef. It’s just the most magical place.”

She had earlier studied English literature and worked for the BBC, producing science and environment documentaries. But the changes to the reef that Lucas saw before her own eyes after moving to Australia led her to work to fight climate change.

“So many places that I knew and loved that were bright, colorful corals, many fish, you go back and they’d be bleached and you go back again and they’d be covered in algae, they’d be brown, the polyps would be dead,” Lucas said. “They’d just start washing away. The fish would be gone. Places that were like coral cathedrals just became brown, algae kind of wrecks.”

Lucas is now a climate scientist and leader of Curious Climate Schools, an expert-led climate education initiative in Hobart, Tasmania.

Understanding the nature of climate change

Tasmania is where I grew up. It has a population of just half a million, but it is bigger in land area than Denmark, where I now live, and almost half of its land is wilderness or protected areas. It’s home to ancient rainforests, alpine plateaus and endemic species like the Tasmanian devil.

To many, Tasmania’s identity is deeply linked to its nature.

Lucas moved to Tasmania in 2006 and started a family. When her kids were small, she began to study public attitudes to climate change. Eventually, based on her own ongoing research and on the research of her colleagues and research students, she realized that information about climate change and climate action was greatly missing from young people’s education.

One of her doctoral students, Charlotte Earl-Jones, conducted a survey of young Australians aged 15-19 and found that young people don’t feel comfortable speaking to adults about climate change.

“They feel quite comfortable often talking to their friends about climate change, but they tend not to feel comfortable talking to adults,” Lucas said. “And they’re not talking to their parents, they’re not talking to their teachers. And that’s because they don’t feel that those people are really listening to them or taking them seriously.”

Lucas and her students put a call-out on ABC Radio in Tasmania, asking people all around the state to send in questions about climate change.

Questions and answers

Then they sent climate experts around the state to answer the flood of questions that had come in. They wanted to put children in the centre of their own education around climate change.

“To take them seriously, to validate their worries and concerns and to make sure that they actually feel that they are being listened to,” she said. “And that we are meaningfully responding to their worries, because they are the generation who will be facing the most climate impacts of any previous generation, and that’s a big thing.”

Lucas and her team found that many of the questions were based on existential concerns. People wanted to know if it was already too late to stop climate change and they wondered how long they had left. Many questions presupposed that humanity is doomed.

“So that was really the catalyst for me thinking, well, we should be doing this in schools,” she said. “And at the time I was in conversation with my kids from primary school, and one of the teachers wanted me to help with a climate change unit there, or a bit of teaching around climate change. So I sort of put the two together and I thought we should be doing this much more broadly in Tasmania.”

Curious Climate Schools works with students and teachers in various capacities. They started by asking schools to gather their students’ questions about climate change and to choose 10 to ask a team of climate experts.

Climate change as part of basic education

Curious Climate Schools then found the right experts for the right questions and made a series of videos where these questions get answered. The experts include not just climate scientists who are looking at the atmosphere and oceans, but also researchers who are looking at fire, people who are looking at climate law, all kinds of areas around climate change.

The videos are accessible on their website, but are also shown in classrooms. And sometimes experts go into the classrooms to answer the questions live and to inspire students with their journey into climate research and climate leadership.

“It seems from our research that many students get to the end of their schooling and they still have not really learned about climate change, or they haven’t learned the things that they think they need to know,” Lucas said. “So they may have learned just a bit about the greenhouse effect, which is useful, but that’s not what they’re interested in. They want to know what we’re doing about climate change. And fair enough.”

Lucas said that some studies have found that some 17% of young people believe the world will end in their lifetimes. Curious Climate offers them education that is reassuring in some way.

“The world is not going to end in their lifetime,” she said. “It may be harder. There may be challenges. But we’re trying to look at ways that we can make changes now and in the future so that we can thrive in whatever climate future we end up in and to think about the future in positive and regenerative ways.”

Fighting the fear of climate change

Curious Climate Schools has developed cross-curricular units that explore different aspects of climate change. They found that teachers need help teaching climate change not only because they don’t feel that they have the time or the expertise to do so, but also because they’re worried about the anxiety and despair they might be instilling.

The cross-curricular units encourage teachers to work together so that the social science teachers, for example, can take one lesson plan and science teachers another.

Since more than a third of the questions asked were about what actions are being done about climate change, Curious Climate Schools focuses on three types of action: individual, collective and systemic.

“And we suggest that individual action is important and backs up collective and systemic action, but obviously you’re getting a bigger effect for those kinds of actions that you can do together,” she said. “And we think it’s particularly important not to make young people feel guilty. Many of them do.”

They feel guilty that they’re not recycling correctly or that their parents are buying particular products that they think are bad for the environment and it is important that they not feel like the fate of the world hinges on their specific actions.

“You know, it’s great to do those things where you can and do your best but not everyone has the capacity to do all those things all the time,” Lucas said. “It’s about what more of us can do more of the time.”

Developing resilience

At Curious Climate Schools, teachers might try to get students to think about what kinds of changes could be made in their school that would help it to be more resilient to climate change like cooling it or reducing its emissions. For systemic change, they might talk about ways to influence political leaders or big companies.

A last component of Curious Climate Schools is a classroom game called The Heat is On, a role-playing game that is set in 2050 in a climate-changed world on an island much like Tasmania but called Adaptania.

“So we have five teams and each of those teams is like a town council,” Lucas said. “We have a capital city that’s vulnerable to heatwaves particularly, but is also a bit vulnerable to bushfires on its peri-urban fringe. And then we have another town which is vulnerable, particularly to bushfire, one that’s vulnerable to flood, because it’s on a flood plain.”

The students get effort points and adaptation cards. They can spend the points on adaptations such as green streets, public water parks, and developing wetlands. Each adaptation includes a number of effort points equivalent to how much work it would take and information on how much more resilient it will make the town.

The students in their teams work together to decide what they’ll do to make their town more resilient to climate change.

When the time is up, a big wheel called the climate extremes wheel gets spun, whereby the climate disaster or effect of the year occurs, whether that be a bushfire, flood, biohazard and so on.

And depending on the adaptations decided on by the team and on the climate extreme that occurs, each team receives a resilience score against the NESH resilience index — nature, economy, society and health. There is also a town that is used as a control in the game to show what happens if nothing much at all gets done. It’s called Bludgeton.

“So you get to see a town where nothing happens and they basically fall apart,” Lucas said. “You see their circle of resilience just diminish to nothing. And then they can see how the decisions they have made have made a really noticeable difference.”

Three questions to consider:

1. How can climate change education make young people feel guilty?

2. What focus on climate change does Curious Climate Schools take?

3. What worries you most about climate change?

Amina McCauley is News Decoder’s Climate Education program manager. Born in Australia and living in Denmark, Amina has a background in reporting, media analysis and teaching and a particular interest in the relationship between humans, their environment, and the media.