After four decades and some 40 millions deaths, can we end this worldwide health crisis?

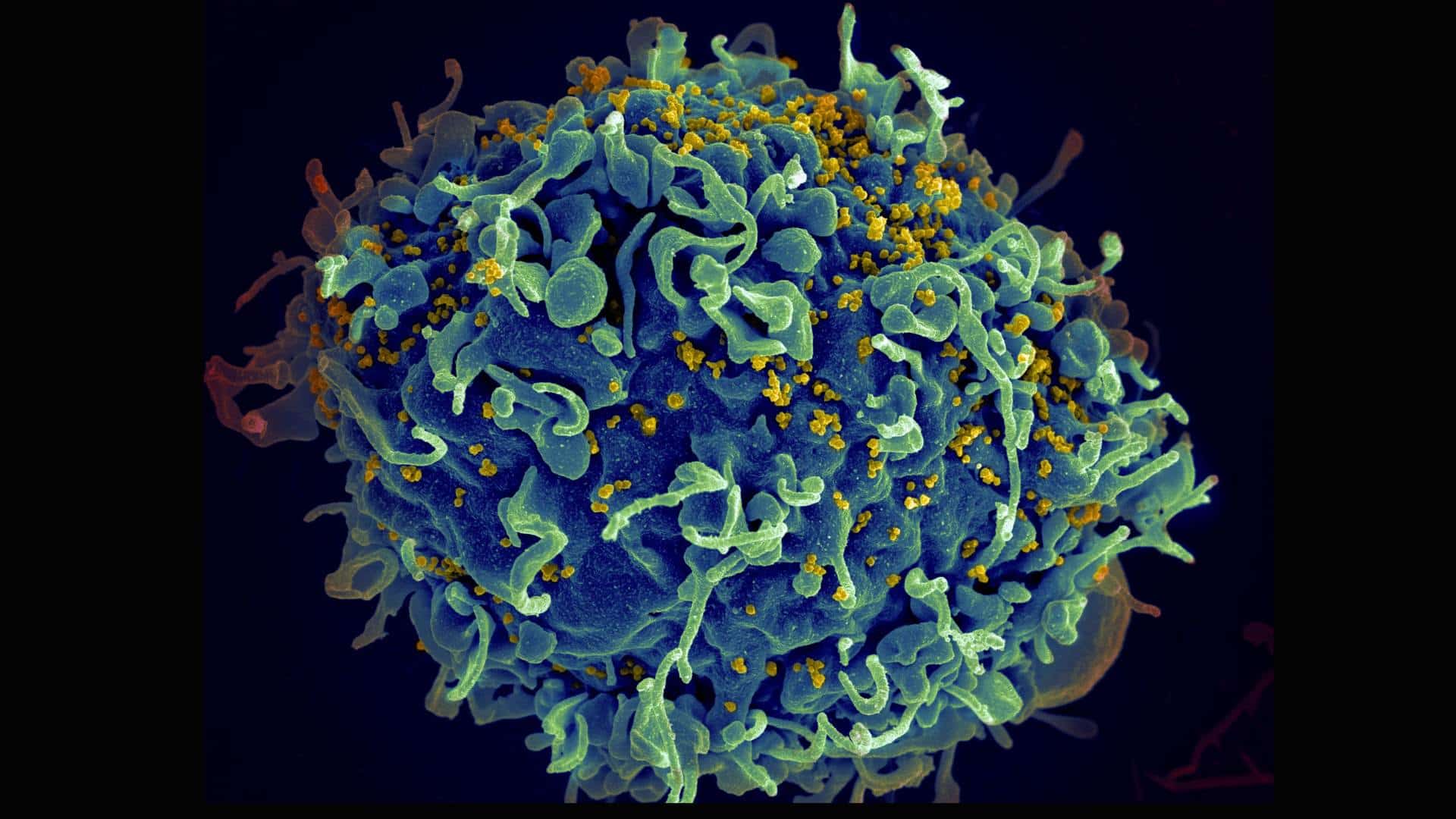

A human T cell (blue) under attack by HIV (yellow), the virus that causes AIDS. Credit: U.S. National Cancer Institute

This article was produced exclusively for News Decoder’s global news service. It is through articles like this that News Decoder strives to provide context to complex global events and issues and teach global awareness through the lens of journalism. Learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program.

A test of a new drug designed to prevent the human immunodeficiency virus or HIV, showed that it prevented the virus that causes AIDS in all the participants in the trial. Of the 2,300 women in Uganda and South Africa who received lenacapavir, a drug developed by Gilead Sciences, Inc., none acquired HIV during the follow-up period.

“It’s a breakthrough advance with huge public health potential,” said Sharon Lewin, president of the International AIDS Society.

It was one of the breakthroughs presented at the World AIDS Conference in July. Around 9,000 people — academics, activists, decision-makers and pharmaceutical industry representatives — gathered in Munich to share information about Acquired Immuno Deficiency Syndrome, a disease that has killed more than 42 million people around the world, according to the World Health Organization — 630,000 last year alone. But the tide may be turning.

“We can end AIDS,” said Helen Clarke, former New Zealand prime minister and former administrator of the United Nations Development Programme. “The issue is not the lack of tools to do it.”

Treatment for HIV has been available since the second half of the 1990s. HIV drugs can lower the level of the virus in the body until it can no longer be detected in the blood. At that point the chance of transmission is unlikely.

Preventing AIDS transmission

“Undetectable = Untransmittable” is an international campaign that promotes treatment, both for the well-being of a person living with HIV, but also to prevent new cases. Additionally, preventive medicine for people without the infection can reduce the risk of acquiring the virus by 99% if used daily.

The confidence expressed at the AIDS conference marked a big shift from the atmosphere that marked earlier meetings.

The first AIDS Conference was held in 1985, two years after the Pasteur Institute in Paris identified HIV. The epidemic was a public health emergency that had begun four years earlier in U.S. cities, where it affected mainly gay men. By 1985, there were cases all over the world. In the 1990s it would spread to the general population of sub-Saharan African countries, becoming the core of the epidemic.

Since the appearance of HIV, those who carried the new disease were singled out and marginalized. Fundamentalist religious groups spoke of divine punishment, and, referring to gay men, called it a plague that condemned the immoral. People with HIV were fired from jobs or removed from their families. In some countries, this still occurs.

The administration of U.S. President Ronald Reagan ignored the crisis. In response, Act Up, a collective of artists and activists in the United States, came out with the slogan “Silence = Death” to demand a proper response to the emergency.

Social activism to spur government action

In a presentation during this year’s conference, Georgetown University Professor Lawrence Gostin noted the effectiveness of AIDS activism. “When Act UP started chaining themselves and throwing fake blood, that’s what changed things,” Gostin said.

HIV has shown that health is also a political and social issue. In response to HIV-related activism, several countries, like New Zealand in 1986, erased laws criminalizing homosexual relations. In the early 2000s, activists from the Global South, such as Brazil and South Africa, demanded the overthrow of patents on existing HIV drugs so that treatment would reach those who needed it, not only in rich countries. Governments responded.

“We not only benefited from democracies but also reinforced democracies,” said Veriano Terto Jr, a Brazilian long-time academic and activist. Several Latin American countries followed Brazil’s example. International cooperation funds boosted treatment worldwide.

According to The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS new HIV cases have been declining globally for several years, but not everywhere. For example, said Omar Sued, the regional advisor for HIV Treatment and Care at the Pan American Health Organization, new infections are on the rise in Latin America.

“At the beginning, Latin America was a leader in treatment programs,” Sued said. In the 2000s, all countries in the region implemented programs to secure universal access to treatment.

However, the region has lagged in incorporating current strategies such as HIV self-testing or preventive medication that could reduce new cases. Meanwhile, Sued said, barriers in many health systems prevent the best use of existing resources.

Ending AIDs across populations

The 95-95-95 Goals, international targets set by the United Nations, state that 95% of people with HIV should know their diagnosis, 95% of these should be on treatment and 95% of those on treatment should have undetectable viral levels.

But these targets don´t address social aspects. “You don’t see particularities of specific populations,” says Mariana Iacono, who has been living with HIV for 22 years. “Who are the ones who die? Who has access to medication and doesn’t take it? How do you work with those people?”

Iacono is from Argentina and has been an activist for 19 years. She co-founded the Latin American chapter of the Network of Young People Living with HIV. Nowadays, at 42, she leads the breastfeeding initiative for mothers with HIV at ICW, the International Community of Women Living with HIV. “It’s a new topic,” she says.

The medical guidelines state that mothers with HIV should use infant formula instead of breast milk, Iacono said, but there aren’t enough studies to determine if those guidelines should still be followed.

“In some countries in Africa there has been breastfeeding for many years because there is a lack of drinking water, no formula, but there´s no data,” Iacono said.

Gaps in public health still exist

Iacono sees her cause as a struggle for autonomy. “For 40 years they told (women) what to do,” she said. “Not to have sex, how to give birth, not to breastfeed.”

It is still activism that continues to point out the scientific and public health gaps, she said.

The outlook at the conference was not entirely optimistic. Funding for the HIV response is decreasing. Above all, there was widespread concern about the advance of ultraconservative groups.

Clarke, in her speech to conference goers, said that many of the populations most vulnerable to HIV are the targets of anti-rights movements.

“They are emboldening homophobic, transphobic, misogynist elements around the world,” Clarke said. “They are a real threat.”

As it has been for the past 40 years, the fight for health is also a fight for social justice. “Anyone whose rights are on the line,” Clarke said, “we need to come together.”

Three questions to consider:

- How can science benefit from social activism?

- Why do you think the world was so slow in fighting AIDS?

- How did the beginning of the AIDS crisis differ from the way the world tries to fight pandemics — like Covid — today?

Alfonso Silva-Santisteban is a public health physician, researcher and photojournalist based in Lima, and a former fellow in global journalism at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto.