In a key stop in a global cocaine network, residents of Durán are trying to just live their lives in a place that has become the murder capital of the world.

A handcuffed resident is led away during a military and police operation searching homes for weapons and drugs in a neighborhood of Guayaquil, Ecuador, 16 October 2024. (AP Photo/Cesar Munoz)

This article was produced exclusively for News Decoder’s global news service. It is through articles like this that News Decoder strives to provide context to complex global events and issues and teach global awareness through the lens of journalism. Learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program.

Every 20 hours, a murder. Durán, an Ecuadorian city with barely 300,000 inhabitants located just outside the port of Guayaquil, has become the stage for a violent little-noticed battle with repercussions in places as distant as Belgium or the United States.

The cocaine that moves through its streets does not stay in Ecuador; Durán is a key point in the transnational network that enriches drug cartels and the gangs that control the territory.

In 2023, Durán shattered records for violence, with a homicide rate surpassing 147 per 100,000 residents, making it the most violent city in the world outside a war zone.

It wasn’t always like this.

“My neighborhood used to be a place where you could walk in the early morning, without fear,” recalls 35-year-old Blanca Moncada. “The elderly sat in chairs outside their homes, children played soccer all day and families had parties on the weekend.”

A town suddenly made dangerous

When Moncada left her hometown during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, Durán was just another average Latin American city: dangerous, yes, but not overwhelmed by violence. It ranked 453rd in the global crime index, close to Lima, Peru.

The horrors Moncada speaks of are almost unthinkable: children shot dead in front of their homes while playing, entire families decapitated in gang revenge killings, a self-imposed curfew by residents too terrified to be caught outside after dark.

Businesses are shutting down or going bankrupt because they can’t keep up with extortion payments to criminal gangs.

One stark fact: in the past 18 months, Durán has recorded more than 30 massacres — six times more mass killings than in the past 12 years, according to InSight Crime. A massacre is defined as any single violent act resulting in at least three murders.

“It was never a city without problems,” said Leonardo Gómez, journalist and researcher who was awarded a prize for his investigative reporting by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy in Madrid, Spain. “Half of the population does not have access to potable water and almost half of the land is irregular, in the hands of land traffickers.”

That, according to Gómez, is Durán’s deadly trap: a city abandoned by the state, as if it were a remote border town, yet located just 10 minutes by car from Guayaquil, Ecuador’s second-largest city.

Power of the drug trade

How does this misery connect to organized crime? In the vacuum left by the state, criminal gangs quickly learned that whoever controls the water and land, controls the entire territory. According to police reports, drug trafficking in Durán has infiltrated everything: the city council, the fire department and the traffic agency.

Where state authorities don’t reach, the gangs sell illegal plots of land to low-income families, who end up indebted to the same criminals. These gangs also supply water in areas where the state cannot intervene, charging exorbitant prices and using control over the resource as a tool of intimidation.

Politics, as in many crises, has played a crucial role in Durán’s downfall. Carlos Moncada, 56, moved to Durán in 1986, when it was a booming industrial hub destined to be Guayaquil’s bedroom community. Today, he can’t even visit.

“I was threatened,” he says, matter-of-factly. Moncada had supported his daughter’s campaign for a seat on the municipal council, which she eventually won. “It’s a nightmare; she never imagined they would be living through this. They’re still working virtually.”

On 14 May 2023, minutes before Durán’s newly elected mayor, Luis Chonillo, was set to arrive at the city council for his inauguration, an armed group attacked the official convoy. Two police escorts and one of Chonillo’s staff were killed.

Since then, Chonillo’s team operates under police protection and virtually, more focused on their own safety than on implementing any governance plans. Chonillo has only been able to visit the municipality once and a bomb threat kept it to 15 minutes.

Government inaction

Given the collapse of local institutions, it was expected that the national government would step in as promised by President Daniel Noboa, who tried to demonstrate the state’s power last summer by entering Durán in a military tank, surrounded by special forces and helicopters.

“The mafia’s days are numbered,” he proclaimed.

However, by the next day, Durán had counted seven more deaths, then five and so on. Massacre after massacre, until the government stopped addressing the issue in triumphant tones.

“Durán is a little worse than it was a year ago,” the president recently admitted in a television interview.

The violence is often attributed to the endless gang war between the Latin Kings and the Chone Killers, youth gangs turned into sophisticated criminal organizations. But if Ecuador has learned anything — after placing five of its cities among the 10 most violent in the world in 2023 — it’s that violence is not static.

“This won’t end with bullets,” said Gómez, speaking from Madrid, Spain, where he’s traveled to receive his award and cool down after facing threats. For him, and for many others, it’s clear that Durán is a ghost town: without press, without industry, without a functioning municipality, without government.

To fix the problem, the first thing that must be done is to look at Durán again. “Not just the state,” Gómez said. “Journalism isn’t looking at Durán, nor civil society, nor sports.”

Thus, the first challenge facing the most violent city in the world is to get someone to look at Durán again — once more, after burying its dead.

Three questions to consider:

- How can the drug trade affect communities even when the drugs are sold elsewhere?

- Why do you think news organizations in Ecuador generally ignore the violence happening in Durán?

- Do you think that countries where cocaine is largely sold, like the United States, bear responsibility for what happens in places like Ecuador that are ravaged by violence from drug trafficking?

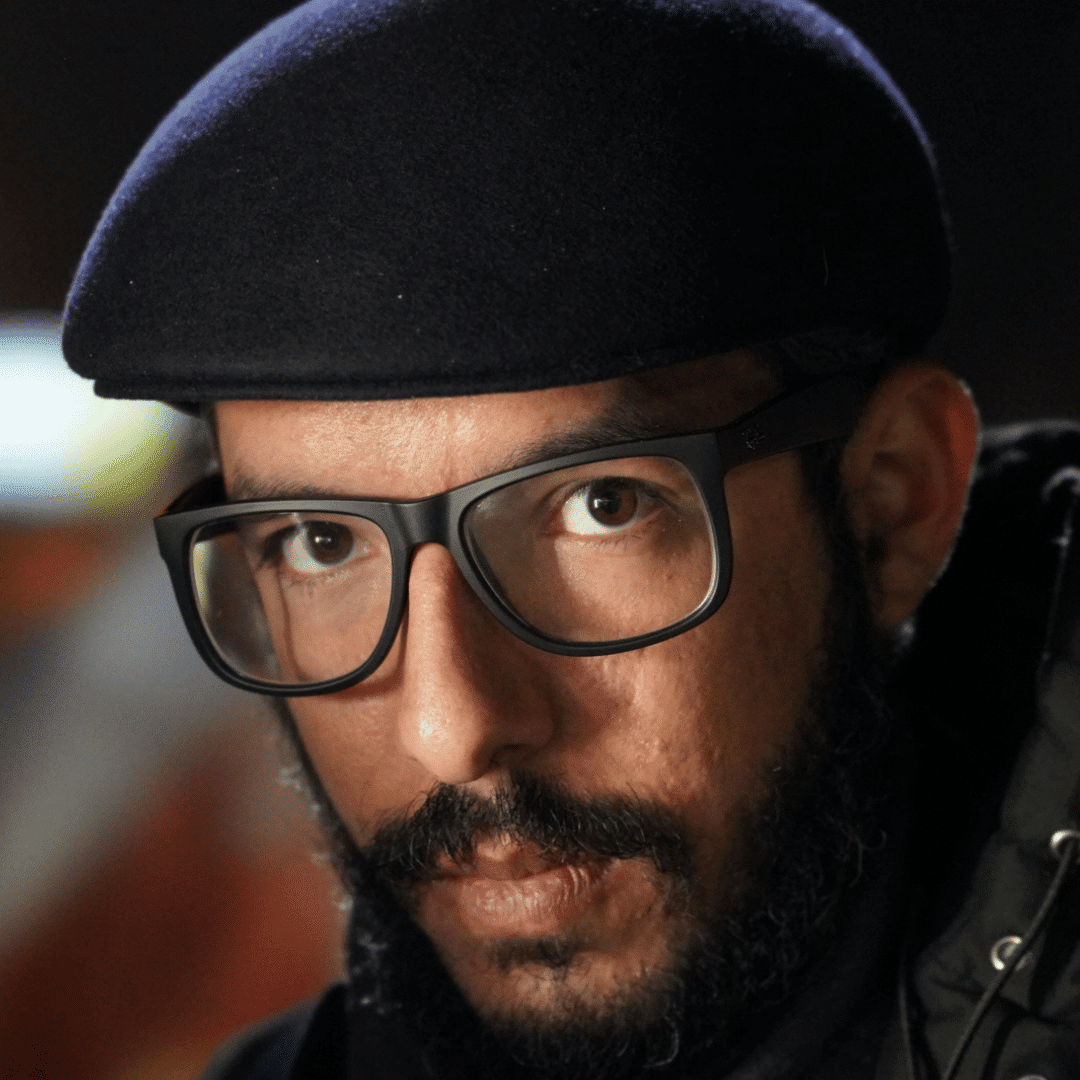

Andersson Boscán is an award-winning investigative journalist from Ecuador, specializing in political and drug trafficking coverage in Latin America. He is currently living in exile in Toronto, Canada where he is a fellow in Journalism and Public Health Impact at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at University of Toronto.