One young Ugandan activist says its time for her generation to stand up and exercise the power their constitution gives them.

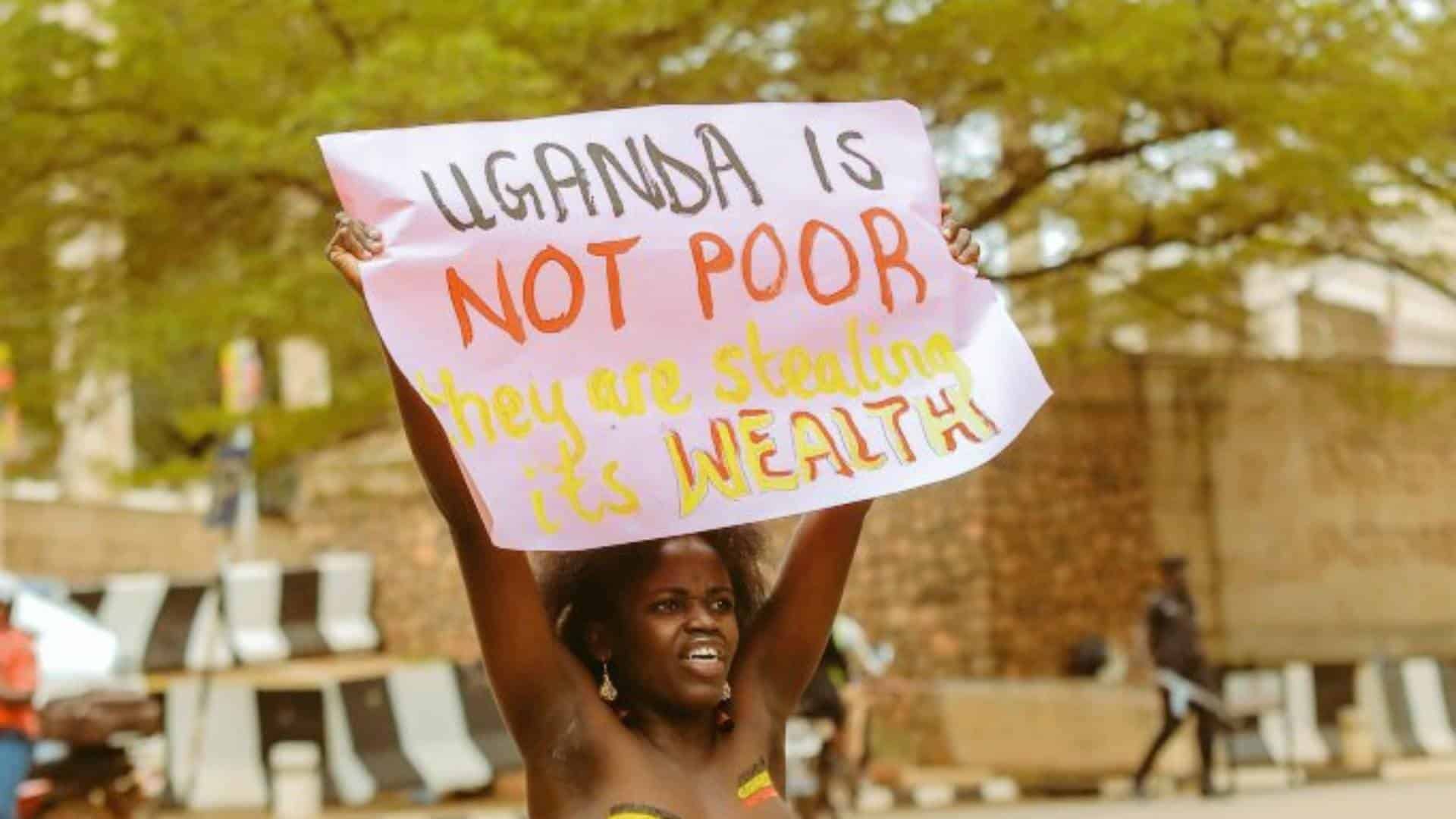

Aloikin Praise Opoloje staging a naked protest in Kamapala, Uganda, 21 September 2024. (Photo courtesy of Aloikin Praise Opoloje)

This article was produced exclusively for News Decoder’s global news service. It is through articles like this that News Decoder strives to provide context to complex global events and issues and teach global awareness through the lens of journalism. Learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program.

In August 2024, a giant landfill in Uganda collapsed burying homes at the edge of the site and killing 21 people. It was a wake up call for Aloikin Praise Opoloje, a young woman who had recently been released from prison for protesting against government corruption.

“We couldn’t just sit back,” she said. Documents showed officials had been warned about the landfill a decade earlier, but nothing was done.

“How do you let people live like that?” Opoloje asked, recalling images of families forced into makeshift shelters after eviction. “It wasn’t bad luck; it was leadership failure.”

She knew action was necessary and that it was time for a bold protest. She thought about a “cursing ceremony.” In traditional African culture, women expose their bodies to curse those who wronged them. Opoloje reimagined this act of vulnerability as a source of strength.

“Forget the colonial legacy of sexualizing women’s bodies,” she said. “What if the very thing meant to silence us could be a source of power?”

She and two other women painted their bodies with the words “No Corruption,” and on 2 September 2024 took to the streets with only their pelvic areas covered.

Exposing the naked truth

The message was clear: shame the corrupt and demand accountability. Their capital statement was designed to be impossible to ignore.

“It’s not the shame of being naked,” she said. “It’s the shame of a system that lets this happen. If the price of justice is bearing that shame, then so be it.”

Police arrested the three woman and Opoloje found herself in jail for the second time.

Her first stint in jail came after Kampala’s youth took to the streets in an unexpected act of defiance. Crowds marched toward Parliament, chanting “Anita Must Go!” — a collective cry for accountability, fueled by allegations of corruption and the misuse of public funds.

The protest was sparked by a social media exposé that revealed widespread corruption within Parliament, exposing what the Daily Monitor described as the “House of Deals.”

This wasn’t just a rhetorical jab; it was a pointed critique of a system where public funds were misappropriated and policies shaped by personal interests. Fed up with the corruption, Opoloje and her fellow activists sought to hold the government accountable, though they faced the daunting challenge of fighting a regime that had long silenced dissent.

The question loomed: Could their efforts succeed against a regime that had perfected the art of quashing opposition?

A peaceful protest could end in violence.

For Opoloje, the protest represented more than a political challenge; it was an effort to break a deep-rooted cultural silence that had kept many Ugandans from speaking out.

“People will fight over football teams, but no one will take to the streets for better healthcare or against corruption?” she said. “We waste so much time making excuses for why we can’t change things, but we’re willing to risk our lives for things that don’t matter.”

The march faced fierce opposition. President Yoweri Museveni labeled the protesters “foreign-funded agents” and warned they were “playing with fire.”

And despite two months of preparation leading up to the event, only a few hundred people showed up, and most were arrested before even reaching Parliament. Meanwhile, inside the parliamentary session proceeded as usual, unaffected by the unrest outside.

Opoloje wasn’t disappointed. “The protest was a victory,” she said. “Not because we toppled the government, but because we awakened something in people.”

The protest marked a turning point for Uganda’s younger generation, many of whom were born under the nearly four-decade-long rule of President Yoweri Museveni. It was their first tangible experience with political defiance — an act fraught with danger but charged with a sense of empowerment. And it ignited a critical conversation among young people.

“They’re asking questions, challenging policies,” she said.

The protests triggered a swift response from President Museveni, who warned that dire consequences awaited those detained during the protests.

Opoloje, though, had faced fear and danger her whole life. Just over a year earlier, when she was at the hospital about to give birth, her struggle was with a failing healthcare system. In the hospital, she watched the midwife try to manage multiple births at once. Opoloje could tell she was exhausted.

“One of the women was in critical condition, but the surgeon who was supposed to operate was nowhere to be found,” Opoloje said. “We tried calling him, but he wasn’t picking up.”

When Opoloje gave birth, she was told there were no sutures to repair a tear she had sustained. “I lay there for 45 minutes after the tear,” she said. “I started to pass out.”

Only when her mother handed the midwife some money did the sutures suddenly appear. Yet the anesthesia didn’t work, and Opoloje endured the procedure awake.

Making constitutional rights real

The experience at the hospital was a harsh reality of Uganda’s broken healthcare system.

“You can only imagine how many deaths that midwife must have witnessed — babies born with no incubators to keep them alive,” she said.

Opoloje challenges the belief that power belongs to a select few. In Uganda’s constitution, she said, power resides with the people but few Ugandans can exercise that power and too many believe that only those in power can demand basic human rights.

Opoloje’s frustration extends to corruption, which she sees as a deep moral failure. She recounted an example where officials diverted funds meant for shelters in Northern Uganda to build homes for livestock.

“Animals in better homes than humans,” she said.

Silence is unsustainable.

Opoloje challenges the notion that speaking out against injustice is opportunistic. “Are there issues in this country that are reserved for certain people to talk about?” she asks. “If I’m following what the constitution says … it’s my duty, my right.”

Accusations of opportunism ignore the deeper reality of systemic inequities, she said. “What is the opportunity in someone being beaten in the streets and thrown into a police van?” she said.

The growing frequency of human rights violations — such as police brutality and voter suppression — makes silence increasingly unsustainable, Opoloje insists. “If more people spoke out, it wouldn’t seem strange when someone calls out an injustice. It would just be part of the daily conversation.”

She believes that the true beneficiaries of silence are those in power, who prefer the status quo. “The government thrives on this mindset,” she said. “They want you to stay indifferent, to convince yourself that it’s not your place to speak out.”

For her, the call to remain silent only serves to perpetuate the unresolved issues that the government seeks to maintain. “Overthrow the constitution, if you will — but don’t accuse me of something I’m meant to do,” Opoloje said.

Opoloje is pushing for constitutional reform, ensuring that the guiding principles of the constitution shaped every aspect of governance. “We have a wonderful constitution,” she said, “and if we truly adhered to its principles, we could make significant strides in improving the political and social systems of this country.”

The constitution clearly prohibits corruption and even specifies punishments for those who engage in it, she said.

“If we followed our constitution to the letter, corrupt leaders would be held accountable, and the fight against corruption would gain real momentum,” Opoloje said.

Safety in numbers

Opoloje’s activism is deeply intertwined with her family’s expectations and worries. After her controversial nude protest, her mother’s response was predictable — concern, frustration and even a suggestion that they might need to “lay hands” on her, thinking she was “demon-possessed,” Opoloje said. The absurdity of it all was not lost on her.

To avoid emotional talks that might make her second-guess her actions she made a pact with herself: “Never share protest plans with Mom.”

Still, the 25-year old longs for a different life. She would like to have fun and hang out with friends, cooking and watching movies. But her activism, she insists, is a matter of survival. “I’m fighting for the soft life I want,” she said. “I’m pushed to the wall, and I have to do these things.”

In a country where dissent is met with brutal force, Opoloje recalls a conversation with her brother: “If you’re threatening me with death, who’s going to live for a thousand years?” he asked her. “We’re all going to die either way.”

Opoloje believes she has outgrown fear: “It’s just one bullet through your head, and you’re gone,” she said “No more pain for you. The pain is maybe for the people who care about you. But you’ve seen people move on.”

Meanwhile there are many ways to die in Uganda, she said. “It doesn’t matter if you’re protesting or not. A car accident — bad roads — death finds you all the same.”

But death wouldn’t be as much a risk if everyone got involved.

“It’s because only a few people are speaking out that they can easily target us,” Opoloje said. “But if everyone spoke up … they couldn’t touch us all.”

Questions to consider:

1. What were young people protesting over in Uganda in the summer of 2024?

2. Why did Opoloje think that a small protest was a success?

3. Would you risk arrest for something you believed in? Is that a real risk where you live?

Enock Wanderema is News Decoder's correspondent in Uganda. He has written articles about identity, the environment, wildlife conservation and politics. He loves writing and bringing complex stories to life in the simplest ways.

Unbelievably brave