In Japan and elsewhere, governments grapple with a frightening future: Too few young to support too many old. How big a problem is this?

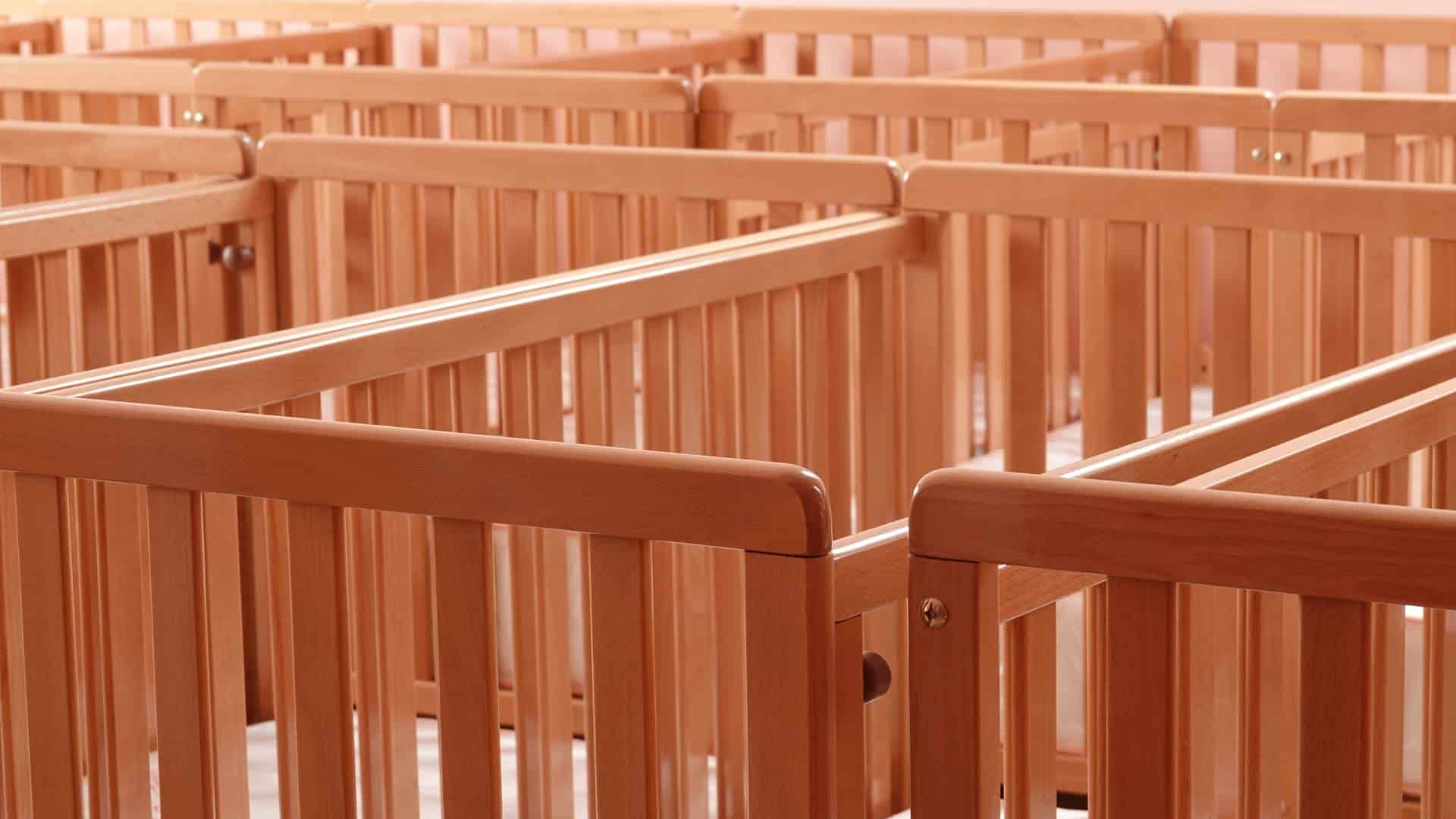

A maternity ward full of empty cribs. (Credit: Urosh Petrovic from Getty Images)

This article was produced exclusively for News Decoder’s global news service. It is through articles like this that News Decoder strives to provide context to complex global events and issues and teach global awareness through the lens of journalism. Learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program.

In September, Japan’s biggest producer of diapers will stop making them for babies. Instead, it will produce them for elderly people. The reason: birth rates are at a record low in the country with the world’s highest life expectancy.

The decision by the diaper maker, Oji Holdings, followed government statistics that showed the lowest number of births since the 19th century. In contrast, the proportion of the elderly has increased steadily and people over 65 now make up a quarter of the population, government statistics show.

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has called the dwindling number of births “the biggest crisis Japan faces.” Despite a range of measures that include subsidies for child birth, children and families, there’s no end to the crisis in sight.

Kishida’s crisis declaration brought to mind a remark by one of the loudest doomsayers about the effect of fewer babies: Elon Musk, the billionaire entrepreneur who uses his social media platform X to share his opinions with millions of followers.

The present trend, according to Musk, threatens to end civilization. It will end, he has said “not with a bang but a whimper, in adult diapers.” Musk’s own contribution to fight falling birth rates: He has fathered 12 children with three women.

The world ages.

Japan is Exhibit A of a global trend demographers call global aging. In popular terms you can call it baby bust and oldster boom. It is a phenomenon that requires rethinking the way societies are organized.

No country has fully figured out how to cope with rising expenditures for the pensions and healthcare of the swelling ranks of senior citizens while the number of young people shrinks. According to United Nations forecasts, the number of people over 65 will double in the next quarter century while those over 80 will triple.

From Tokyo to Beijing to Berlin, Paris and Rome, governments have tried a variety of measures to handle a demographic transformation without precedent.

According to Richard Jackson, president of the Global Aging Institute, a Washington-based think tank, the elderly accounted for a small fraction of the population, never more than 5% in any country for most of history.

That began to change after the industrial revolution in the 19th century which saw major advances in medicine and a sharp decline of children dying before their fifth birthday. For decades, populations grew with fertility rates well above the 2.1 children per woman needed to keep the numbers stable.

Now, the 2.1 “replacement rate” has dropped in much of the world. In Japan, it stands at 1.3, in South Korea at 0.8. If that continues, the country’s population is projected to fall by 60% by the end of the century.

Persuading women to have children

Government attempts to persuade women to have more babies have varied from country to country and range from cash payments and extended maternity leaves to tax breaks. In Russia, women who have a child before they turn 25 have been promised exemption from income tax for life. A similar scheme in Hungary pegs the age at 30.

In the United States, where fertility rates dropped from 3.6 in 1960 to 1.66 now, former president Donald Trump has promised “baby bonuses for a new baby boom” if he wins election in November.

But rewards to entice couples to have more children have had little or no success, for a simple reason. “You can’t bribe women to have children,” said Jackson of the Global Aging Institute. To get the balance between fewer babies and more old people right, the logical answer would be to keep older people in the workforce for longer.

But that logic runs into an obstacle difficult to overcome — fixed retirement ages. How difficult?

Ask French President Emmanuel Macron. Last year, he signed into law an increase in the state pension age from 62 to 64. Across France, more than a million people took to the streets in angry demonstrations against the reform.

Panic in the press

Since the French protests, the biggest in decades, more attention than usual has been focused on the topic of demographic change, which does not often make headlines. But in the past few months, weighty publications have devoted space to the decline of birth rates.

In May, The Economist magazine published a cover with the headline Cash for Kids, illustrated with a baby bottle filled with pennies. Inside, it detailed a long list of incentives governments have been offering for women of fertile age. The report’s conclusion: “Policies to boost birth rates don’t work.”

A Wall Street Journal headline found that “There Aren’t Enough Babies, The Whole World is Alarmed.” European and South Korean publications also expressed alarm in the wake of a new study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development which said declining birth rates will permanently alter the demographic make-up of world’s largest economies over the next decade.

Forecasts of doom bring to mind fears of demographic disaster of the 1960 and 1970s which proved spectacularly wrong. They were triggered by the 1968 publication of a book entitled “The Population Bomb” by Paul Ehrlich, a Stanford University professor. He predicted that unchecked population growth would outstrip food supplies and result in worldwide famines.

Such predictions were among the reason why the leaders of China, then the world’s most populous country (it was overtaken by India last year), decreed that Chinese couples were allowed to have only one child. China’s massive experiment in social engineering was meant to ensure that population growth did not outpace economic development.

A more children policy

It took the Communist Party 36 years to admit that its fears were unfounded. The one-child policy was scrapped in 2015, allowing for two children. Six years later, it encouraged three children. But despite the call for bigger families, statistics from the 2020 census (China holds one every 10 years) showed the lowest population growth since the 1930s.

Perhaps because conventional wisdom about overpopulation in the 1960s and 70s proved wrong, long-range forecasts about societal changes should be taken with a pinch of salt. Today, an under-reported minority of experts argue that population declines should be a cause for celebration instead of alarm.

“Most strategies for boosting birth rates fail because many women are having fewer children not because they can’t afford them or don’t have time for them but simply because they don’t want them,” said Kirsten Stade, a conservation biologist and spokeswoman for Population Balance, a nonprofit organization whose motto is Shrink Towards Abundance.

One of the books that Population Balance recommends to explain their disagreement with the prevailing consensus is “Decline and Prosper!: Changing Global Birth Rates and the Advantages of Fewer Children.”

The author, Vegard Skirbekk, is a Norwegian population economist and professor of population and family health at Columbia University. He argues that most of the assumptions that prompt alarm about fewer babies and more oldsters are wrong.

“All those funds wasted on baby bonuses would be better spent on strengthening support systems for the elderly,” Stade said.

An earlier version of this story identified Kirsten Stade as a marine biologist. Stade is a conservation biologist and spokeswoman for Population Balance.

Three questions to consider:

- Do you think people should have to retire at a certain age?

- In the run-up to the U.S. presidential elections, there have been calls for cognitive tests for politicians over 75. Do you think that is a good idea?

- Do you think that women should be given money to have children? Why?

Bernd Debusmann began his international career with Reuters in his native Germany and then moved to postings in Eastern Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Latin America and the United States. For years, he covered mostly conflict and war and reported from more than 100 countries. He was shot twice in the course of his work: once covering a night battle in the center of Beirut and once in an assassination attempt prompted by his reporting on Syria. He now writes from Washington on international affairs.

Very interesting article, especially because it presents opposing thoughts. I would add that women simply don’t want children because it’s simply too hard. A bonus incentive hardly covers the required car seat for 1 child.

AI and robots will kill a lot of jobs in the near future. If there are fewer babies, then there will be fewer unemployed workers. Less people means less strain on natural resources and that’s actually exactly what we need now.

Sorry, pro-lifers, I don’t believe in your “Philosophy” of people being resources. People consume resources and at the current rate we are using them up at a speed that is threatening all life on planet Earth.