We may not recognize them, but we all undertake quests. They can be grand and cinematic, or quiet and reflective. They all change our lives.

Hanuman, the flying monkey god. The quest in search of Hanuman’s mountain took Paul Spencer Sochaczewski some 30 years to achieve. (Photo courtesy of Paul Spencer Sochaczewski)

This article was produced exclusively for News Decoder’s global news service. It is through articles like this that News Decoder strives to provide context to complex global events and issues and teach global awareness through the lens of journalism. Learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program.

Consider classic films — “Star Wars,” “The Wizard of Oz,” “Die Hard,” “Casablanca,” “Gone with the Wind” — which feature a hero, either male or female, who undertakes a journey to uncover a mystery, right a wrong, seek fame or fortune or happiness.

Now think of the great cultural and religious myths — the Knights of the Round Table, the Odyssey, the Ring Cycle, the Mahabharata, Beowulf, the Epic of Gilgamesh, Faust, the Divine Comedy — which explore similar “searching-for” dynamics.

Philosopher Joseph Campbell called these archetypal scenarios the Hero’s Journey. And I suggest they are as important to you and me as they are to Luke Skywalker or Dorothy from Kansas.

Consider the turning points in your life where you are presented with choices — which university to choose, which lover, which job.

Life never stops presenting us with choices, and the way you embrace these adventures irrevocably changes your life. You go through one door (which loudly shuts behind you), and you enter a changed reality. If it’s a fictional story, you might call it the Narnia Wardrobe Effect or Alice’s Rabbit Hole.

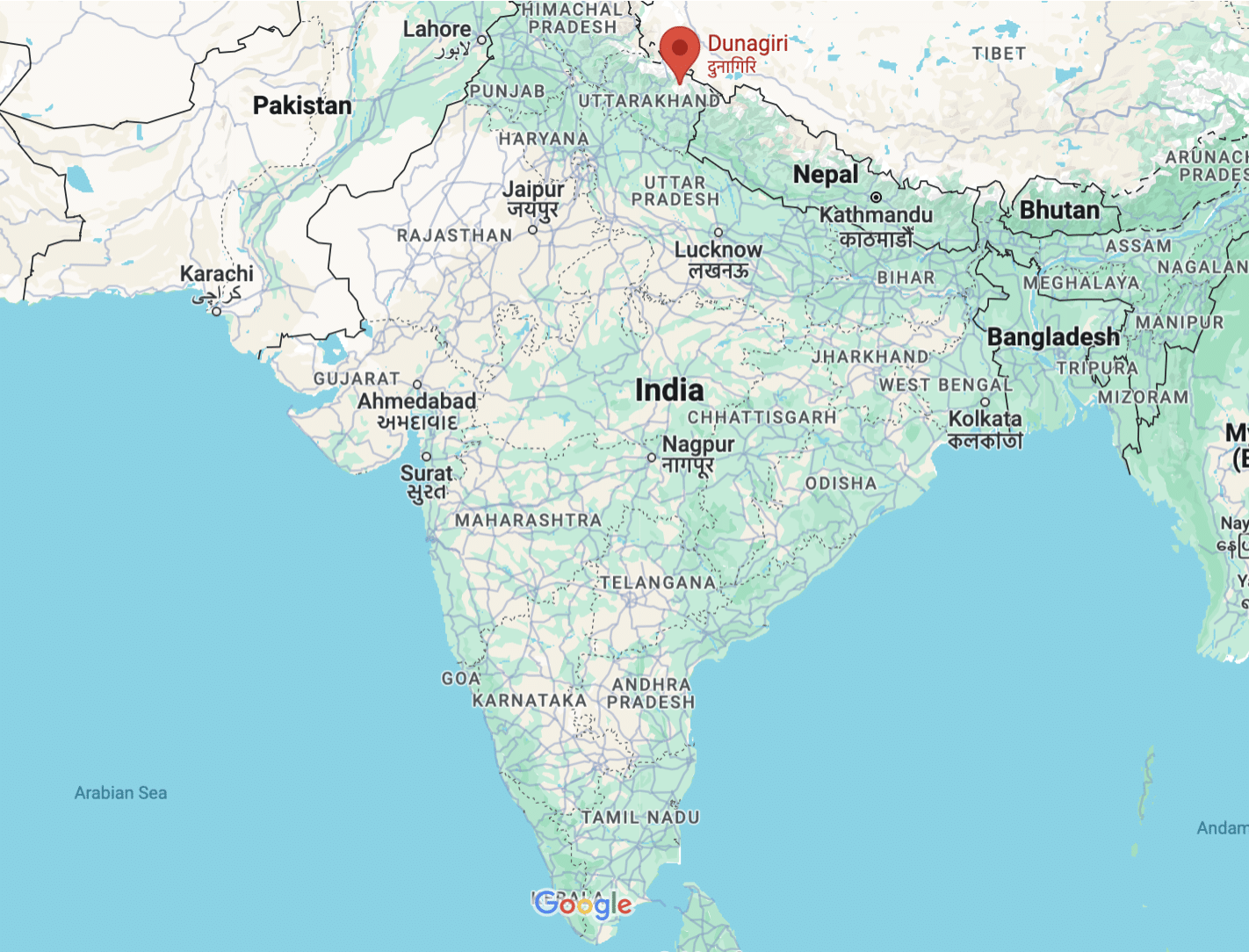

Dunagiri Mountain, on the left, thought to be Hanuman’s medicinal plant mountain. A large red scar indicates where villagers think Hanuman sliced off a huge chunk of healing real estate. (Photo courtesy of Paul Spencer Sochaczewski.) On the right a map showing Dunagiri’s location in Northern India.

Surprises smack you in the face, and you must deal with unsuspected idiosyncrasies, unwanted dramas and edgy encounters. Take more steps, and other doors appear, and you choose one to go through. And on. And on.

But often we consciously choose to enter new portals simply because, well, that’s part of living a good life.

Seeking meaning in ancient myths

Some 40 years ago I became interested in Indian religion-mythology. I was particularly fascinated by the climactic scene in the grand epic poem the Ramayana, in which Rama and his faithful brother Lakshmana voyage from northern India to what is now Sri Lanka to rescue Rama’s wife Sita, who had been kidnapped by Ravana, the ten-headed king.

During one of the many battles, Lakshmana is severely wounded. Their doctor says he could cure him, but he needs special medicinal plants.

The problem (and there’s always a problem — the concept of “no” drives all storytelling) is that the life-saving plants grow in the Himalaya, thousands of kilometers away. So, who you gonna call?

The flying monkey god Hanuman volunteers. He soars to the mountain (and he has to complete the task before dawn — all good narratives also involve a ticking clock), but, being a monkey, on arrival he forgets which plants to collect.

So he rips off the mountain, carries it back to Lanka, Lakshmana is cured, he and Rama win the ensuring battle and there’s a bittersweet ending. The side benefit is that it’s hard to fly across a sub-continent carrying a mountain like a pizza delivery guy without clods of earth falling. These dirt droppings flourished and became sacred forests, now found throughout Asia.

Hanuman’s tale appealed to me not only because of its cinematic-like grandeur, but because I’ve worked in nature conservation my entire career and have been impressed by how sacred forests and holy groves are protected by communities as “life reserves.”

It took me decades to locate Hanuman’s mountain (the original texts are mysterious and vague). But I found a likely geological feature, and wise scholars nodded in approval. It took me decades to organize a guide and find the time, but I eventually trudged up a mountain path to visit Dunagiri mountain in northern India, and found an old lady, Padhan Patti, who not only confirmed that the majestic snow-covered peak behind her house was indeed Hanuman’s mountain, but that she was angry with Hanuman for the cavalier manner in which he treated her “auntie” who, she said, accompanied Hanuman to the mountain but was then abandoned by the monkey god in the wilderness during a blizzard.

Big themes, small stories

My decades-long interest in the white elephants that symbolize the power and legitimacy of the kings of Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and Burma, took me all over the region, culminating in the story of how a poor farmer in southern Laos, Boun Samsy, managed to catch a wild white elephant.

He enjoyed fame and modest fortune for a few weeks, and was about to trade the white elephant to a Cambodian businessman who offered him 10 “normal” elephants in return.

But before he could conclude the deal, a representative of the country’s First Lady knocked on his simple front door and said, in effect: You are honored, comrade, thank you for donating your white elephant to the People’s Republic of Laos because the power-hungry wife of our beloved president wants the animal in order to consolidate her reputation as a glorious queen.

Boun Samsy was forced to ride his elephant for three days to the country’s capital of Vientiane to donate his prized possession. He received no thanks nor compensation. The first lady, Thongvin Phomviharn, is now a lonely old woman, a short cynical footnote in the nation’s history.

My quests are personal. So are yours.

Most of the quests I consider personally important and particularly interesting have similar long

gestation periods, such as my decades-long quest to understand the power of the Queen of the Southern

Ocean, a mermaid queen who is the spiritual consort of two important sultans in central Java.

The quest to learn the truth about my Romanian aunt, who claimed to be of noble birth and a protégé of Queen Marie, took me to Transylvania, her birthplace, where I learned of her numerous lies, exaggerations and biographical inventions, all done with valid intentions.

Some quests are sparked by a single paragraph in a book, as my search for the “lost Jews of Kisar,” a tiny, isolated island in eastern Indonesia.

I don’t collect quests, but I value them.

Some people are deep divers (often earning a doctorate along the way) and spend a lifetime pursuing a single theme — searching for a cure for cancer, fighting for equal education for girls or stopping tropical forest destruction.

Other people string together a series of physical feats — climb all 8,000-meter peaks, swim the English Channel, bicycle across Mongolia. Obsessions? Perhaps. Of value to the quester? Certainly. Selfish and irritating? Often.

The hero’s journey in our daily lives

Quests do not have to involve travels to distant lands; they can be pragmatic and close to home. Many people wouldn’t call themselves heroes at all, but nevertheless engage on hero’s journeys as they earn a college degree, join a big law firm, learn to windsurf, visit Paris, master the art of puff pastry, give long-term comfort to an ailing relative, recover from an illness, get elected to public office, become a professional musician or raise a child.

It’s great to have goals, but regardless of the objective you set, you are likely to encounter the frustration of catawampus, in which life ignores your best intentions and events take an unwanted turn.

As the saying goes, “if you want to make God laugh, tell Her your plans.”

Yet not all quests need be clearly signposted. You could engage in coddiwomple, a travel in a purposeful manner toward a vague destination. And sometimes you just need to go with the flow and follow the advice of baseball sage Yogi Berra: “When you come to a fork in the road, take it.”

I was a founding member of a group in Geneva called the Burlamaqui-Sundberg Society, an informal gang of professional, mostly expatriate men who gathered to eat, drink, talk and exaggerate. We took our name from Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui, an 18th-century Geneva-based philosopher and professor of “natural law” who wrote that the quest for happiness is a natural right.

According to our society’s version of history, Burlamaqui’s writing influenced U.S. Founding Father Thomas Jefferson to include the term “pursuit of happiness” in the U.S. Declaration of Independence. We could never agree on what happiness was, nor how to achieve it. But one element of happiness, it seems to me, is having a project, a goal, a desire to explore, create and learn.

My quests do not have gravitas or legacy on a grand scale, but they are my stories, my adventures, the results of my own (admittedly often esoteric) curiosity.

What quests have you embarked upon?

Some questions to consider:

- Think of a favorite film or novel. Can you identify the quest? And can you identify the archetypes that Joseph Campbell described?

- Do you agree that engaging in a quest adds value to your life? Or are such activities irrelevant and selfish?

- Are you actively engaged in a quest? Does it matter if you achieve your goal?

Paul Spencer Sochaczewski graduated from George Washington University and served in the U.S. Peace Corps in Sarawak, a Malaysian state on the island of Borneo. He lived in Southeast Asia for 15 years, then moved to Switzerland where he was head of Creative Services at World Wildlife Fund International. He has written 20 books and more than 600 by-lined articles in publications including News Decoder, The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Reader’s Digest, Travel and Leisure. He gives presentations about Wallace, and other subjects, worldwide. He is French-American and lives in Geneva, Switzerland.